“Psychological Safety Will Not Just Bubble up Because People Talk about It.”

Alex, currently, no other topic is so actively requested by our customers as “Psychological Safety.” The concept outlines shared expectations held by employees that their peers will not embarrass, reject, or punish them for sharing ideas or giving feedback. Why do you think this is the case – and why now of all times?

Alex Osterwalder: The concept is not new, right? Amy Edmondson came up with the insight that employees work together better and more productively where trust, honesty and transparency characterize a culture in The Fearless Organisation in 2018. But things changed with the pandemic and increasingly decentralized work. People, particularly young people, have become much more demanding about the workplace. They don’t just want to work anywhere anymore. They want to work at a great place with a great work culture. When the true face of many companies became visible – such as organizations spying on people’s computers rather than measuring results and trusting employees, or asking for constant presence without setting boundaries for remote work time – people suddenly asked themselves: Do I want to be part of this team or that organization?

With power quickly shifting to the employees in the current talent crunch, I assume many are fed up waiting for their workplaces to improve. They demand better cultures. And they vote with their feet when they don’t see an improvement.

How can this be? I mean, the concept is well-known. Every executive I talk to in a wide variety of companies and cultures is sure to nod when the topic of “Psychological Safety” comes up. Have there been so few changes in recent years and decades?

My good friends Marshall Goldsmith and Alan Mulally, who turned around Ford, say, “It might be common sense, but it’s not common practice.” There’s always a massive gap between knowing and doing: It’s not so hard to understand what good leadership is, but it’s much harder to be a good leader in the real world. When shit hits the fan, your behavior will show your true face. And I think the soft skills needed to instill a culture of psychological safety aren’t trained as much as the “hard” skills like accounting, finance, or marketing.

For years, all the experts have said it’s essential to invest in core human skills, from decent communication to empathy to proper listening. And what do people in most companies get? The next course on correct expense reporting!

So guess what? People are not good at it because they weren’t taught how to be good at it.

Then how do you turn things around when it comes to Psychological Safety?

Psychological safety is a concept, and it’s never easy to implement concepts, right? Because you need tools and processes. In this case, start with a rule. Start with Robert Sutton’s “No asshole” rule: Avoid lousy behavior by not hiring the wrong people and focusing on hiring the right people. Ultimately, it’s just a matter of deciding to live a company culture that rewards – not punishes – good behavior. If you want a culture with psychological safety, take people on board who have the characteristics of being able to lead an inclusive organization and create it. Then, place a zero-tolerance policy for certain things that undermine psychological safety.

What are some of those behaviors?

For example, looking at personal agendas and politics more than creating value for customers, the organization and the team. Again, you can put in place drivers that enable a psychologically safe culture and blockers that inhibit a hostile culture. Still, it must be a deliberate choice based on the understanding that the organizational culture can be designed and managed. The concept of psychological safety will not just bubble up because people talk about it a lot. Most people think corporate culture just happens. Well, yes, but if it does, the results are often not convincing, which is why it is noteworthy that it can be designed and managed toward a shared goal.

Take-Aways:

- Psychological Safety is a matter of deciding to live a company culture that rewards – not punishes – good behavior.

- Avoid lousy behavior by not hiring the wrong people, and, as executives and leaders, work with coaches who will take away possible delusions.

- Likely, companies must change their organizational structures and incentive systems to create a culture of psychological safety and radical candor.

You write in The Invincible Company that leaders do not create growth, but they create conditions for growth. So is this a leadership problem? How about bottom-up initiatives?

I believe there’s a specific limitation for bottom-up. So if you have a CEO or senior leadership team that creates a psychologically unsafe space, you can do nothing as an employee but change your jobs. On the other hand, if you’re on a board of directors, you can hire a new CEO, COO, CHRO or CIO who can create the right culture because you’re the ones who are making the decisions. If you have suitable leadership role models, it is much easier to drive a culture top-down than build it bottom-up. I’ll give you an example: I don’t consider myself an asshole, as described in Robert Sutton’s book. But I did realize by working with a breakthrough coach that I was not a good listener and that by not listening, you’re not going to create a culture where people speak up or say things when you want them to say something. If you want them to raise red flags, you must first exhibit the culture that allows them to do so. Now that sounds trivial. But again, it’s common sense, not common practice. So today, after months of work with my coach, I think we have a psychologically safe place to work at Strategyzer. That’s why we’re now working on “radical candor.”

Because everybody is being too nice now?

(Laughs.) I’d put it more like this: Psychological safety is not just about being nice. It’s also about saying the things that need to be said. You can have psychological safety, but still, you’re not moving ahead as an organization.

From my perspective, real psychological safety is when you have radical candor – when people speak up.

And for me, the big thing was to realize that if you love your team members and want to create great work, you will tell them when they screwed up or were doing something wrong. Because you appreciate them, you want them to grow. It’s a sign of love if you care this way. We usually don’t say “love” in business, but that’s it. “Brutal honesty, kindly delivered.”

Unfortunately, leaders are just as delusional as everyone else regarding self-assessment – and without a culture of speaking up, no one will tell them about their flaws. For example, you just said you weren’t a good listener. How did you come to that conclusion, and what suggestions do you have for being more aware?

To tackle this problem, leaders must work with a great coach who will put a mirror in their faces and remove their delusions. Many leaders I have met reached a point where they no longer assess their strengths and weaknesses. They are, for example, a CEO of a large company now; they might even have built it up and shown outstanding entrepreneurship. You tend to think your behavior is good at this point because it brought you there. But, as Marshall Goldsmith says: What got you here won’t get you there. And you need somebody to let you know. Every one of us does.

What is the argument for a professional coach and against people from your team or board?

I think team-wise works in terms of showing results and then trying to get everybody else on board. But then you have two possibilities. One is your leader sees the results, appreciates them, and the fact gets them thinking about what they can learn. The other one is: they don’t. And sadly, that’s much more common. In other words, the plant will grow if you have fertile ground. But in the desert, you know, it’s hardly a cactus that will grow.

Yet everybody calls themselves a “leadership coach” today.

Sure, there are a lot of charlatans, snake oil vendors. But there are lots of great coaches as well. And if you want to get a better leader every day, the only way to improve is to work with professionals who know how to do that.

We kind of underrate how difficult it is to coach and accompany people. Change is notoriously tricky, mainly when it’s about yourself.

So good coaches help you become more aware and reach the next level. Roger Federer had a coach. Lionel Messi has several. We all rely on expertise and advice. So why do business leaders only hire coaches when things are going wrong? Hiring a professional will make you more aware of your flaws and have you covered when it comes to actual change as well.

Let’s say the CEO got it with some help, and now they want to identify the steps to take toward a culture of psychological safety and radical candor. You’re famous for your mapping and tools to get a clear strategy for all things organizational. How do they accomplish the cultural turnaround?

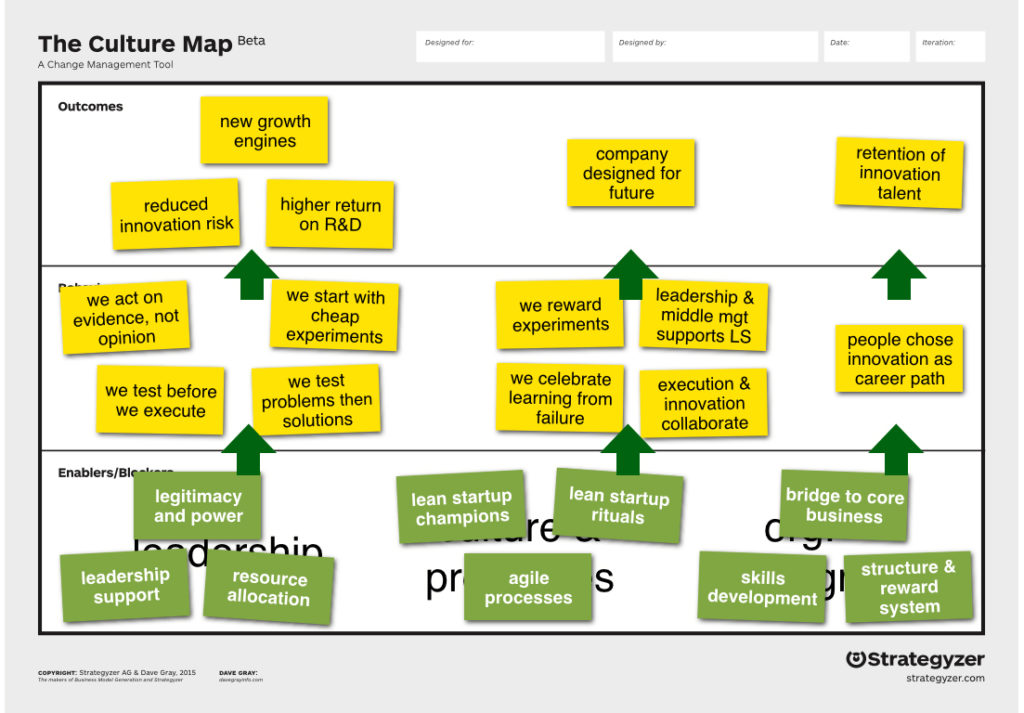

There’s one strategic tool and one tactical tool that I would recommend. So the first, more strategic tool is the “culture map.” We created it together with Dave Gray and Strategyzer. The culture map consists of three boxes: The one on top is the outcome, the desired results of your culture. So this part has to be defined by the top level in advance. The second box, right below it, is the behaviors that lead to those outcomes – the visible part of your organizational iceberg. And at the bottom is the box of the enablers and blockers of your culture.

What exactly does that mean?

It means formal things and informal things. The formal things are, for example, what do you compensate people for to compete in class? Or do you reward people for solid collaboration in teams instead? What processes or rituals do you have? Should you institutionalize or eliminate some of them? Honesty is needed here, and openness.

Use this culture map to map your existing culture, looking at the enablers and blockers and then asking: What could we change? What do we need to change in these formal and informal enablers and blockers to get the behavior we’d want to have to achieve the results we want to achieve? It’s straightforward:

Map your existing culture, map the future state you want – and then manage to go from A to B. Think of it like cultivating a garden: Design and work the fertile ground, and the culture will emerge like a plant.

Let me quickly step in. How do you put this from head to toe? I mean: Having a vision or a goal of a culture on the C-level and communicating it is one thing – but how do you establish a company-wide feedback system regarding the behaviors, blockers and enablers?

From the top, you get vision and guidelines, as you said. And bottom-up, you run workshops from the teams upwards to map the existing culture, the desired culture, and then the path from A to B. From there, it’s project management where you pull it off. That is the hard part. Because, usually, you must change your organizational structures as your incentive systems. Sometimes you’ll have to separate paths from certain people because they don’t exhibit the proper behavior. Some companies have gone that path and even fired high-performance people who completely undermined the culture. But they made it a choice. So it’s top down and bottom up, and hard decisions to achieve your desired culture.

How do you measure success?

When you go from A to B, there are certain things you can measure. Employee satisfaction is measurable, and my favorite tactic is asking people before and after, “Would you enthusiastically reapply for a job at our company?” Or “Would you recommend our company to a friend or a colleague?” Or, even more straightforward: “Did the environment change?” And, of course, the culture map process is not necessarily complete after one initiative – it can continually be repeated. And in the process, new questions will arise that should lead to another improvement. As I said: Progress doesn’t have to stop. It can be part of our very everyday working life.

You mentioned another, more tactical tool to make cultural change happen a few minutes ago. What is it about?

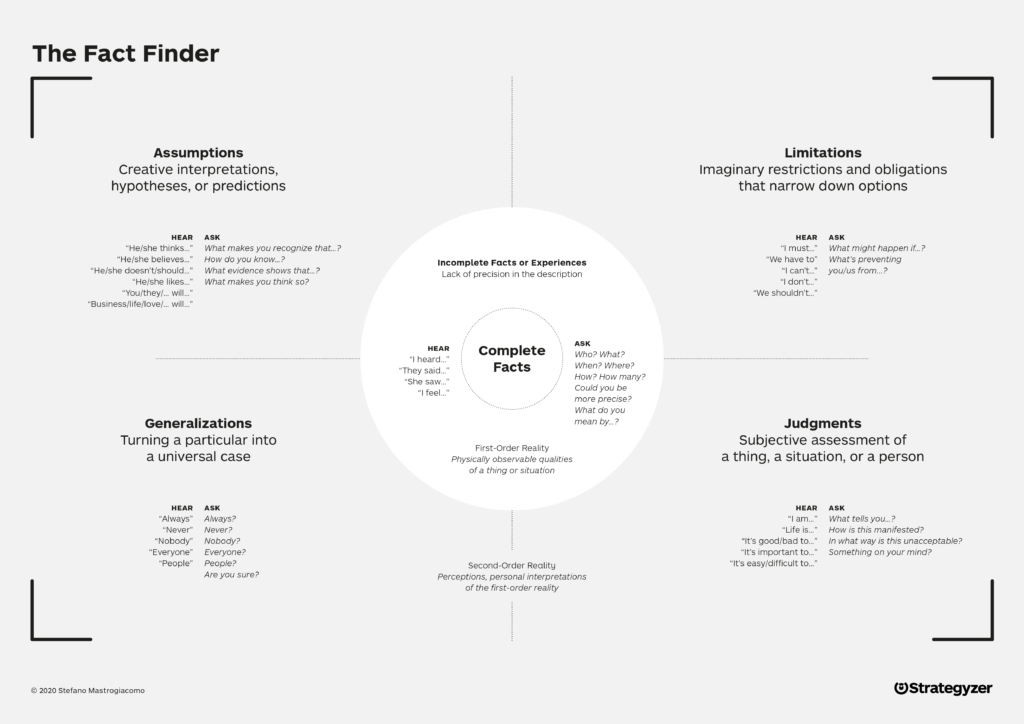

It’s probably my favorite tool in High Impact Tools for Teams, besides the culture map, and it is called “Fact Finder.” Why? Because if you pay attention to how we speak in companies, our language often is not very good. For example, if you ask for feedback on employee satisfaction, you might get an “Oh, everybody is suffering.” Or: “We have no psychological safety.” And those are wrong generalizations that won’t help you move forward. So instead, if you use the fact finder, you’ll get to a more refined language.

For example, you learn that rather than saying, “Everybody’s unhappy,” refining feedback to “I’ve talked to these three people…” makes sense. “All three mentioned they’re at their limits. They’re burning out. That’s a fact.” That makes a fundamental difference because generalizations create the impression that something is a fact, but it is not. The message is more precise and correct if you can highlight your specific findings regarding an issue. The same applies to assumptions.

Can you give another example here?

Sure. Assumptions are all about impressions. “They didn’t like me.” People say that a lot, but most of the time, that’s an assumption. So, what’s your evidence here? Did you talk to them? Did you ask them? Maybe they were annoyed because they spoke to their partner on the phone and were fighting. You know what?

The first thing we needed to eradicate at Strategyzer was assumptions.

How did you do that?

Whenever I heard someone make a point based on a personal impression, I asked them to talk to the people to clarify those assumptions. So again, that’s easier if psychological safety and radical candor are already built into your organization’s culture. However, having those conversations will also strengthen a culture of openness and trust. And the fact finder helps you create that sane language and takes away a lot of emotional pressure from these generalizations and assumptions. By using it, all conversations within your organization will lead to better outcomes, laying a whole new foundation for collaboration.

About the Author:

Alexander (Alex) Osterwalder is the founder & CEO of Strategyzer and one of the world’s most influential strategy and innovation experts. A leading author, entrepreneur, and in-demand speaker, his work has changed the way established companies do business and how new ventures get started.

Learn more about the topics discussed in this interview in the following Journal articles: