“Pettiness Costs a Lot of Time, Money And Morale.”

Alex, your book The Price of Pettiness is about workplace niggles and how they affect the workforce’s morale. You’ve studied the whole thing scientifically, collected lots of case examples and conducted surveys: What does pettiness cost us?

Alex Alonso: Suppose you have to spend your working time in an irritable, pettifogging environment. In that case, you – and many more people in your organization – will waste a lot of that time on rehashing and arbitration, which leads to frustration, loss of efficiency, loss of team spirit and last but not least, massive turnover in the workforce. If you take a step back from the actual cases and their potential consequences, you find that businesses currently invest a lot of resources to describe and optimize their organizational cultures. For instance, you hear a lot about empathy and employee engagement today. But: I think assessing pettiness is another way of describing an organizational culture, because pettiness is an essential indicator of a workplace climate. That’s why I, for example, recommend that organizations do one thing when somebody is about to join: Have them take our Pettiness Index. Let them go through the list of 35 different examples of petty behavior in the workplace to see how they react.

Why?

There are two reasons you might want to do that: First, it’s an easy metric to identify just how bad somebody can be. The Pettiness Index ranges from 0 to 300, and the worst-case scenario is somebody ends up in the 300 range. That is where applicants told you basically that they will be very time-consuming and nerve-wracking to your colleagues. So, you might want to consider that in their assessment because this tends to become expensive in many ways. However, the other thing that it does is cause people to think about what they’re petty about! Just taking the assessment makes them consider: OK, now I know when I’m not funny and what I shouldn’t be putting forth. People start to dial back their pettiness once they take the assessment. It also makes sense for people who are with the organization for a long time. And as a manager or leader: Put yourself to the test! You’d be surprised how petty you are even though you are sure you are not. (Laughs.)

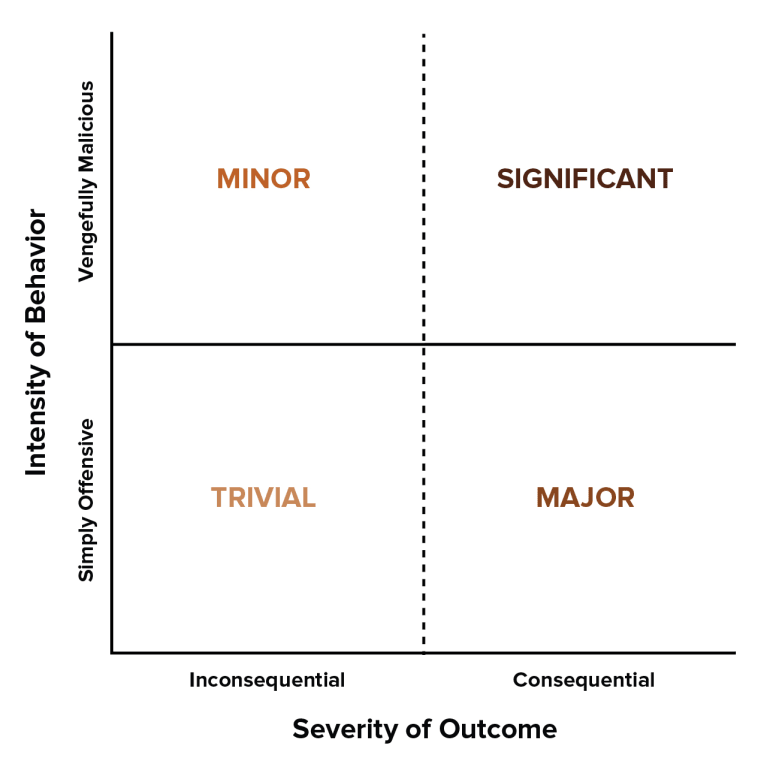

Let’s dig into this: The Pettiness Index results in four quadrants with different qualities – trivial incidents, minor incidents, major incidents, and then significant incidents. What separates these quadrants from each other? Where does an incident become a major incident, for example?

Well, we overlaid these quadrants across the hundreds of examples that we have collected so far. And I’ll share with you two of the latter that aren’t even in the book but have always stuck with me. We had somebody that called in one day and shared an example of petty behavior where somebody stole a Kleenex tissue from their desk. They considered somebody taking a Kleenex without permission as a minor offense, a petty offense. Their response to it was to go and say something to that person and tell them never to do it again.

Now, on the other hand, that borrowing person will see them as petty in approaching this but still consider it a minor incident, so the effect on both sides is minimal, and they eventually settled the case. The other example that I think of is the exact opposite: An individual in the same position said they saw somebody borrow a Kleenex from someone’s desk to wipe their nose. And that third party then decided to call the police and report the issue. That’s a significant shift because, aside from the fact that the police have to go ahead and investigate this case, it no longer only affects the individuals involved. It involves several other groups in and outside the organization. It costs a lot of time, money and morale to go through these investigations and smooth the waves again. To top it all off, the affected company then decided that they would end the reporting person’s career by firing them. That’s an example of a minor incident turning into an enormous disaster.

Wow, that escalated quickly! And it seems the reaction to a pettiness incident is as important as the initial incident itself: Reporting to the police seems inappropriate, but is there any rule of thumb on how to react appropriately?

As a rule of thumb, ask yourself: Can you walk away from the situation? Let’s take an example from the book that deals specifically with a new nurse in a hospital and how she is outshining all the older nurses. The more senior nurses decided to put a fish, a dead fish, in her car. So, could the older nurses have walked away and chose not to engage in that behavior? The answer is yes. We preach the rule to walk away for 72 hours, to give yourself the chance to come back and assess how important the scenario is, how important the behavior. If the behavior after 72 hours is essential, then the next question you ask yourself is: What is the specific issue that I’m trying to respond to? Is it the individual and the way that they present themselves? Or is there a particular behavior that causes the problems with the nurses? It’s not that the individual was younger or prettier or anything like that. In this case, she was just doing more in her shift than the other ones, and she was more efficient.

She was also breaking the pace of work that was expected.

Yes. And by finding out what such an underlying cause is, one can tackle it without tackling the other side. The third question you ask yourself, and the most important one, is: What are the outcomes of addressing this in a specific way? What is the range? There’s anything from “I may upset this new employee, this new nurse” through to “I’m going to do something that creates a criminal offense or something that provokes an incident that is so bad that we all could never recover from.” And if you cannot recover from it, is this even worth exploring? I’d say: Putting a fish in the new nurse’s car is not worth it. That becomes an employee relations issue that you can never recover from. So, the most considerable undercurrent of everything that I’m describing here is patience.

The unlimited elixir for pettiness is patiently walking away, coming back after 72 hours, and reassessing the situation.

Alex Alonso

According to a 2019 Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) Pettiness in the Workplace survey, 75% of respondents said petty culprits suffered no official consequences. But, of course, minor incidents are minor issues, so they rarely become public, and maybe that’s a good thing – after all, everyone has the right to make mistakes and get a second chance…?

Sure. I always say: Be patient, but if it happens the third time, you have to do something about it. Then, it would be best if you addressed it. You just need to monitor what it is that you do to address it. Don’t do something that is so career-limiting that you end up hurting yourself. Beyond that, though, you can go to HR and raise the issue.

How about a confrontation?

Direct confrontation is not advised. We find 95% of individuals who are petty or can be classified as petty, being that they’re 100 or above on our scale, they can’t control themselves. And I say this as somebody who himself has had that experience: It’s hard to control yourself in a direct confrontation when somebody is engaging in specific kinds of behavior. So instead, go ask someone else. No, it doesn’t have to be a formal authority. It doesn’t have to be the supervisor. It doesn’t have to be your HR department. You can go ask your co-workers and say, “Hey, I’m struggling with this. Could you please help me talk to so-and-so about this?” That way, you have somebody who supports you in this. And here we’re touching on the point that led me to write the book. May I add this example?

Please go ahead!

I was in the line at McDonald’s with my daughter. Being the “Prince of Pettiness,” as my team colleagues call me, you might imagine my reaction when my order was left incomplete for the third time in a month, and I was losing precious time with my family trying to rectify the matter. Little did I know the attendant was a classmate of my daughter, Madeline. She witnessed my dismay and asked me to consider how best to approach him requesting a remedy for the situation. Rather than losing my cool, she helped me see the consequences of pettiness and saved her classmate a world of unnecessary anger. Consideration of consequences in a self-reflection is a sign of patience, which always stems the tide of pettiness.

But let’s say that won’t work: When is the right time to ask for help from a supervisor?

When someone’s safety is violated or an instance where someone cannot engage in their work without some repercussions.

One thing to note about involving a supervisor or HR is that it will have consequences, and it will have the kind of consequences that will affect not just one party, but both – whether we like it or not.

Alex Alonso

The truth of the matter is that even the person who brings things to light will be viewed as either standing up for themselves or someone who simply loves to complain about others. I’ve seen it time and time again, and it’s the reason that only one percent of these interactions are ever reported. People don’t want to include those things and don’t want to have those repercussions. But, eventually, what ends up happening is you must, and you’re looking at how you go about being an advocate for others or being an advocate for yourself.

Many examples in your book, which is enormously worth reading, revolve around acts of passive aggression. Your book follows an exciting format: Unlike other business books, you rely on the power of examples, without adding pages and pages of “to-dos” and “best practices” to these. Was that a conscious decision?

Part of the writing style is a catharsis, and part of the writing style is also helping people see themselves in others. People appreciate the handful of tips on how to handle pettiness in the workplace. Still, they recognize that this is so pervasive that it’s better to see the depth of the pervasiveness by examples and then know how to assess it. Together with my team, we are currently working on a book on polarization and how you talk about it in the workplace. And we’ve decided to do the same thing here because there simply is no cure for each of the reported examples. That isn’t something that you usually do with management books, as you point out. But honestly: You don’t always have the solution right away.

Sometimes you need to see all the angles and then figure out what might be appropriate for you.

Alex Alonso

Most of the examples you come up with in the book deal with physical interactions. Will the shift towards more hybrid workplaces soon ease the tensions regarding petty behavior a bit – or will it be the exact opposite?

Currently, we’re observing two scenarios where it is exacerbated or made worse by the pandemic. First, if you have a workforce that is either partially co-located or partially remote, what ends up happening is that we see more petty practices from those that are in the office physically. They manifest in two ways. One is in participation. So, for instance, I might, as somebody who’s in the office, say “I’m going to be petty to my co-workers who aren’t or have never had to be in the office.” I might go a step further and exclude them from specific scenarios and so on. The other example is managers being petty about how people are returning to the office or choosing not to return to the office. Some now refuse to give people the opportunities they deserve in career advancement if they decide to stay at home or work remotely.

Yes, these ways existed before, especially during the pandemic, but are being applied more frequently now. In addition, we see more discrimination against those who are not vaccinated – they are being shamed in many workplaces, which drives a wedge into the workforce. I am sure that the problems here will become much more apparent when we move towards hybrid workplaces, and that makes it even more important to take the matter seriously and to address it in companies.

What do you personally do to reduce pettiness incidents in your daily work? Do you actively remind yourself about the worst cases?

What my roughly 70 staff members do is, every Wednesday, they submit what their most telling moment in recent days was, what their involvement was, and what they learned. This way, I get about 60 responses, and every week I get two disparate descriptions of what’s going on in the workplace. This way, we constantly think about pettiness, and think about not being petty, which drives the team. Now, granted, they know that if something is awful, I’m going to put it in the next edition of our book, but the point is that they know that we’re alert to it, and that’s spread throughout the organization. SHRM has about 400 staff members and I’d be able to do an introductory course for every new employee that says, look, these are things that actually happen – even in a place where we constantly think about the issue and how to prevent incidents.

About the Author

Alexander Alonso, PhD, SHRM-SCP is the Society for Human Resource Management’s (SHRM’s) chief knowledge officer leading operations for SHRM’s Certified Professional and Senior Certified Professional certifications, research functions, and the SHRM Knowledge Advisor service. He’s the author of The Price of Pettiness.