More Than a Feeling

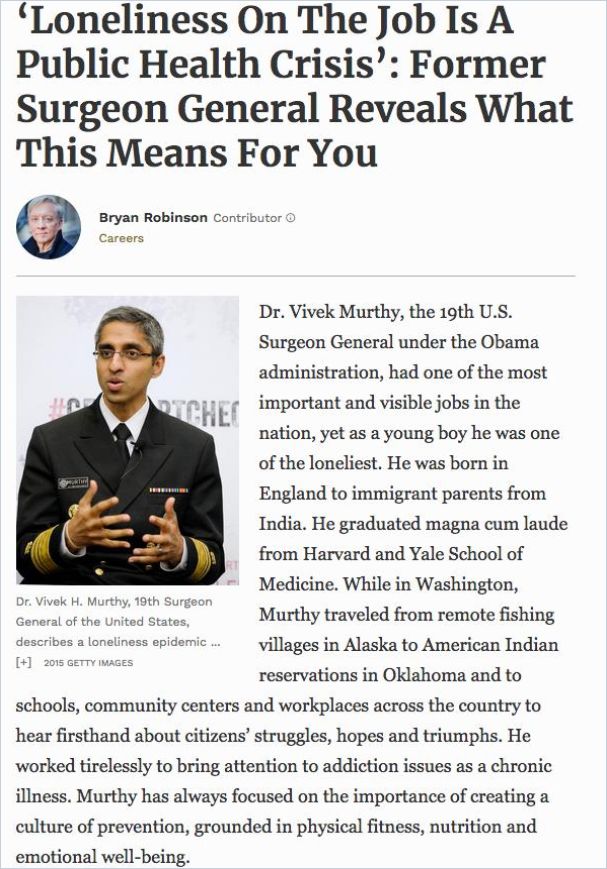

In April 2023, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory to draw attention to an urgent public health issue. But it’s not what you might think. The advisory had nothing to do with a disease outbreak involving biological agents or toxins. The Surgeon General was talking about something that leaves many suffering in silence, even without a medical diagnosis. Murthy was calling attention to his country’s “epidemic of loneliness.” (Find the full report here.)

A Public Health Concern

To his own admission, loneliness was not top-of-mind when Murthy accepted his first assignment as US Surgeon General in the Obama administration. Nor was it the topic he initially thought would frame his memoir upon leaving his post. (Murthy was later re-appointed by President Joe Biden.)

During his first stint as “America’s Doctor” in 2015, Murthy traveled across the country to survey the top health problems affecting Americans. That’s where he began to piece together a common denominator: Underneath the stories of many people struggling with chronic health issues – from addiction to heart disease and depression to cancer – were strong feelings of isolation and loneliness. “As I delved more deeply into the issue and started to understand the science behind loneliness, I came to see that loneliness has consequences that go beyond just feeling bad,” Murthy explained his growing interest in the topic.

The US government is not the first to frame loneliness as a public health concern. In 2018, former U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May appointed the world’s first Minister of Loneliness to tackle what she called “the sad reality of modern life.” The ministry’s strategy, A Connected Society, seeks to reduce the stigma around loneliness and make tackling loneliness a key consideration in policymaking.

In 2021, Japan followed suit by appointing its own Minster of Loneliness, largely in response to the country’s rising suicide rate following the COVID-19 pandemic. The ministry, also in charge of tackling falling birth rates and strengthening regional economies, sees it as its mission to promote “activities to prevent social loneliness and isolation and to protect ties between people.”

Worse than 15 Cigarettes a Day

In his influential 2000 book, Bowling Alone, Harvard public policy professor Robert Putnam detailed how social ties have been weakening in the second half of the 20th century as the number of Americans participating in civic organizations, clubs, religious gatherings – even local bowling teams – has been continuously declining. According to Putnam, these developments have undermined community, wealth, social progress and trust. Recent studies by Putnam indicate that these trends have gotten worse, contributing to rising political divisions and a loss of trust in government. (Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently elaborated on these themes in The Atlantic).

Besides examining the negative social, political and economic consequences of increased social isolation and loneliness, researchers have been documenting a direct correlation between social connectedness and physical health.

In a groundbreaking meta-analysis in 2010, Julianne Holt-Lunstad demonstrated a clear correlation between social connectivity and premature death. Significantly, it showed that people with strong social connections are 50 percent less likely to die over a given period of time than those with fewer social ties.

Quite famously, the study likened the health impact of isolation and loneliness to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

Over the past two decades, research has linked persistent loneliness to depression, anxiety and poor sleep; to hormone disruptions and increased inflammation; to worsening cardiovascular health and type-2 diabetes; to lowered immune function and decreased stress resilience; and to dementia.

A Vicious Cycle

At first glance, the solution to loneliness seems simple: Make some friends! Join a club! Volunteer! Yet people trapped in their lonely caves find it hard to just crawl out of it. Consider the recent collective social experiment we underwent as a result of the coronavirus crisis. How many people’s social lives have really gone “back to normal”? Then there is the stigma surrounding loneliness – the sense that admitting you are lonely will make others think you are not likable or that there is something “wrong” with you.

Most importantly, however, researchers have found that for a social species like ours, perceived social isolation impacts our cognition in a way that makes it harder for us to make social connections.

For example, loneliness has been shown to inhibit our executive function and increase depressive cognition, which both make it harder for us to take proactive steps to break out of social isolation. Also, loneliness has been shown to increase our sensitivity to social threats, which makes us more suspicious of others and more alert to possible signs of rejection – not exactly the frame of mind that will get you a date at the next cocktail party.

Loneliness is Expensive

Loneliness imposes real costs on businesses. Lonely employees are more than five times as likely to stay home due to stress than those who are not lonely. A study based on Cigna’s Loneliness Index data, published in the Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, puts the costs related to stress-induced absenteeism at over $154 billion annually.

This number does not yet include the costs associated with decreased employee engagement, productivity and performance resulting from loneliness. Surveys conducted by Cigna found that people who are lonely are three times more likely to admit they are less productive than most workers with a similar job, and three times more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs than their less lonely counterparts. Furthermore, nearly one in five lonely employees indicated that their mental or emotional health “extremely” interfered with work in the preceding month.

Research conducted by Ryan Jenkins and Steven Van Cohen for their book, Connectable, found that roughly 70% of workers worldwide experience loneliness monthly, and 55% suffer it weekly. Meanwhile, close to 95% of leaders report increased loneliness among remote team members.

Loneliness and the workplace: key findings from Cigna’s Loneliness Index data:

- The longer people are at a job, the less lonely they tend to feel. People who have been at their jobs for at least 10 years are the least likely to feel alone or isolated.

- People who have a best friend at work tend to be less lonely.

- The frequency of in-person interactions strongly correlates with loneliness levels.

- Remote employees are more likely to feel isolated than office-based employees.

- People at the top (senior executives) and the bottom (entry-level employees) tend to be the loneliest.

- Older generations tend to be less lonely than younger generations. Gen Z respondents were more than twice as likely than Baby Boomers to say that they often feel alienated by their coworkers.

- The number of hours worked and the size of the company have no impact on loneliness levels.

Read the full report here.

Taking Action

What distinguishes the loneliness epidemic from a viral one is that we don’t have to wait for a drug or vaccine to be developed. Communities, workplaces and individuals can all do something to create more connections and mitigate feelings of loneliness. In some respects, loneliness is a communal problem – and workplaces have a role in creating the conditions for people to feel more connected and engaged. Ultimately, however, healing starts with the individual – and there is much each of us can do to create more connection in our lives.

1. Strengthen connectivity

The Surgeon General’s advisory calls upon employers to “make social connection a strategic priority in the workplace.” Employee engagement expert Michael Stallard offers a manual on doing just that in Connection Culture: The Competitive Advantage of Shared Identity, Empathy, and Understanding at Work. According to Stallard, a connected company puts people first. It expects leaders and team members to genuinely care for, respect and appreciate each other.

What if the value of work – even work we dislike – lies not just in getting paid, but also in the moment-to-moment sensations of being alive in the workplace and the feeling of vitality we get from being connected to others?

Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz

In Work Better Together, Deloitte chief well-being officer Jen Fisher and researcher Anh Phillips emphasize the importance of face-to-face interactions to create the psychological safety people need to share ideas, be creative and take risks. To foster workplace relationships, the authors advise that companies identify structural barriers such as faulty workplace design, flawed communication logistics and operational silos. In addition, companies must assess cultural barriers such as workism, skewed reward systems and favoritism.

People who love their jobs often cite co-workers as the primary reason they do, yet companies primarily use financial incentives to motivate people, social psychologist Matthew Liebermann observes in a talk he gave at Google. He cites research in economics showing that bottom-line results depend not on human capital per se but on social capital: the connections among employees. One easy way organizations can help employees connect socially is by synchronizing break times: Lieberman points to one study showing that fostering social connection during downtimes had powerful effects on team cohesion, productivity and workers’ stress levels.

2. Improve work-life balance

A sound work-life balance is a prerequisite for good mental health. Workplaces that actively protect people’s non-work time, such as through flexible work schedules and email blackout periods, leave employees with more opportunities to connect with people outside work, such as by joining a club or spending time with family and friends.

As the lead researchers of the longest survey of human happiness – the Harvard Study of Adult Development – authors Dr. Robert J. Waldinger and Dr. Marc Schulz examined data collected on thousands of people from two generations. They found that the most consistent predictor of well-being isn’t money or career success. It’s relationships. In their remarkable book, The Good Life, Waldinger and Schulz offer strategies for improving the quality of your connections, for making new connections, and for bolstering your overall well-being and life satisfaction – at work and beyond.

3. Good communication

Remote work puts people at risk of feeling isolated and disconnected. Front-line managers thus play a crucial role in strengthening connectivity through regular check-ins and virtual – as well as in-person – team-building activities.

Intriguingly, Jenkins and Van Cohen found that regardless of their technologically sophisticated upbringing, members of Gen Z seek the human element at the office. A little more than 70% prefer face-to-face communication at work, and 83% want to interact personally with their managers – though 82% of managers assume Gen Z employees prefer instant messaging.

Leaders can strengthen people’s sense of belonging by clearly communicating each team’s purpose and goals. According to Gustavo Razzetti, author of Remote Not Distant, purpose provides a reason why your employees want to work together. Employees who bond strongly with their teams engage more fully with one another and develop a sense of group belonging that will make them feel more connected.

How Check-Ins and Check-Outs Will Help You to Build Stronger Teams

Medium Read SummaryIf logistically feasible, favor hybrid work arrangements over remote ones, allowing employees to switch between independent assignments done at home and interactive tasks completed at the office. Find ways to maximize the benefits of collaboration and take the necessary steps to prevent a two-class hybrid system.

4. Psychological safety

The Cigna survey has found that people who feel free to be their true selves at work feel less lonely. Working on building an inclusive workplace thus is key. To promote meaningful human connections, workplaces must treat each employee as a human being rather than seeing them as just a set of skills. Managers must become good at knowing how to respect the differences among people in a diverse workforce while pulling everyone together as a team.

As Alla Weinberg explains in her book, A Culture of Safety, creating a feeling of psychological safety in a group is the opposite of merely “being nice.” It requires team members to confront each other and work through their issues, which can feel discomforting at first. Her book offers a series of exercises for starting off staff meetings that will foster connection, respect and a sense of belonging among team members.

In The Psychological Safety Playbook, consultants Karolin Helbig and Minette Norman offer actionable tips for leaders to promote inclusion. For example, they suggest appointing an “inclusion booster” at each meeting to ensure everyone gets a chance to speak. And, to set a rule that “no one speaks twice until everyone speaks once.” Regularly expressing appreciation toward workers is also an important way of making people feel seen.

Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) can effectively foster connections among employees with similar interests and challenges. ERGs are also a way for employees to connect with people outside their immediate work team.

Find more on psychological safety and inclusion in the getAbstract Journal:

5. Individual initiative

Workplaces can set the conditions – but individuals have to do the hard work of pulling themselves out of loneliness. Vivek Murthy shares a few tips. Start by cultivating more meaningful connections with family members and friends – and do so regularly. Furthermore, research indicates that even brief interactions with strangers reduce loneliness and create a greater sense of happiness.

Ryan Jenkins and Steven Van Cohen

Don’t discount the workplace as an avenue for developing authentic and valuable connections with others. As Waldinger and Schulz point out, most people spend a significant amount of their lifetimes at work, so try to make the most of this time.

Another powerful avenue is service: Assisting someone you know or volunteering for a cause doesn’t just help build human connections but also enhances your sense of self-worth by contributing to society. Visit the Surgeon General’s website for additional tips and resources, such as the National Institutes of Health’s Social Wellness Kit.

Most importantly, be patient with yourself. Like an astronaut re-entering life on Earth, you will need to take baby steps to find back to a more connected you – one social interaction at a time. Follow best practices for new habit formation by checking out our dedicated channel and find additional inspiration here: