“You Must Make It Clear That You Really Want People’s Ideas.”

Karin and David, in a nutshell, how do you define a “courageous culture?”

Karin Hurt: Our favorite definition of culture comes from Seth Godin, who says culture is simply, “People like us do things like this.” In a courageous culture, people like us speak up. They are willing to share their ideas. The default is to contribute.

As a company leader, how can you tell whether you have a “courageous” company culture?

David Dye: As a leader, some of the telltale signs you want to look for are whether problems are brought up and resolved quickly. Research around psychological safety has found that the highest functioning teams with courageous cultures seem to have a lot of problems. But in fact, it’s not that they have more problems than other teams, it’s that they’re talking about their problems more and resolving them quickly because it’s safe for everybody to do so. And that’s the cultural norm. If you ask a question like, “How can we improve in this specific area?” do you get a lot of answers or do you get reticence and find people don’t want to raise their hand and speak up? Those are a few places to start looking to see whether your culture indeed is courageous or not.

Karin: If everyone always agrees with you, you probably don’t have a courageous culture. People are challenging one another up, down and sideways.

Many leaders would say, “My door is always open, and I have never punished an employee for saying the wrong thing. So why do people not come in and speak up?” How would you answer this question?

Karin: The problem with an open door is that it still takes some level of courage to walk through an open door. As a leader, you need to be very clear about where you need ideas, and then show up curious and proactively ask people for their input. One way to do this is to ask what we call courageous questions – questions that are specific and vulnerable. For example, “What is one thing that we could do differently to improve this process?” A specific question like this is easy for people to answer. It reduces the friction. And it’s assuming that improvement is possible. Once people start sharing, you can open the conversation for dialogue.

David: Another challenge is that sometimes people don’t know they have a necessary idea or a good solution. The types of questions that Karin’s referencing help draw these out of people when they may not know what they have to contribute. An open-door policy is very passive – it doesn’t proactively, intentionally get you the ideas you need.

What causes people not to speak up? And might some of these factors be outside an organization’s control?

Karin: When writing the book, we conducted some pretty intensive research on this question in partnership with the University of Northern Colorado. One of the most interesting findings was that 67% of people said, “You know what? That’s just the way my manager acts around here.” Or, “This is the way we’ve always done things – so why bother? Nothing’s ever going to change.” Meanwhile, 56% said, “I’m not going to get credit for my idea. So why bother?”

David: Half of our respondents said, “If I were to contribute an idea, nothing’s going to change. Nothing will happen.” Another 49% said, “I’m not regularly asked.” And then you had about 40% of people expressing fear or reluctance to contribute, saying they don’t have the confidence to share.

Make sure you acknowledge and thank people for their inputs.

Karin Hurt

Where does this reluctance come from?

David: Two factors in human psychology are at work here. One is people’s tendency to overweigh negative experiences. Someone might say, “I’m never sharing again. I got shot down once.” An experience like this can hold people back even if it happened 10 years ago and at a different company. The other factor is people’s tendency to discount the future. People often underestimate the benefit that would come from contributing an idea. They may have an idea but think it would not make a big difference. So no matter how human-centered or courageous of a leader you are trying to be, your team members probably have those factors going on. Leaders must be aware of these factors and help people overcome them.

Karin: In our research, we also asked people what kinds of ideas they were holding back – and the issues at stake were not trivial. That’s why it’s so critical to be proactive and make it easy for people to contribute.

Sometimes people don’t know they have a necessary idea or a good solution.

David Dye

Especially with COVID-19 and people working remotely, we may now have an overabundance of sharing platforms. Organizations maintain dozens of channels on Slack or Teams, and people are sharing their thoughts everywhere. Good ideas are at risk of being drowned out or getting lost. As an organization, how do you put a framework in place that ensures important input is heard and answered?

David: Creating clarity is a key step in building a courageous culture. You must make it clear that you really want people’s ideas. And secondly, you must be specific about where you most need a good idea. Strategically, there are probably one to three areas where you could really use a great idea. Once you have established that clarity, create a specific channel or method for people to share their ideas.

Karin: The most important thing to do next is what we explain in step four of our courageous cultures process: Respond with regard. People will stop posting in your channels if they feel nothing is going to happen with their contributions. Make sure you acknowledge and thank people for their inputs. Let them know what you are going to do with their idea or explain why you are not going to act on it at this time. Let people know what’s going to happen with their idea next. This way, people feel seen and validated.

Creating clarity is a key step in building a courageous culture.

David Dye

The way an idea is presented can make a big difference as to whether it will be taken up by leaders. How can companies help employees to make a pitch that will get noticed?

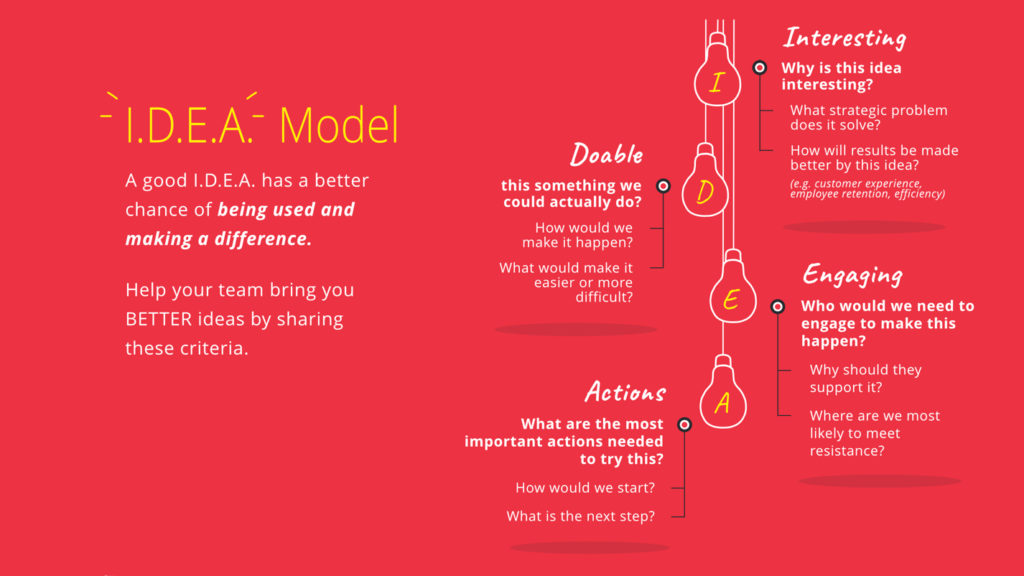

David: One of the methods we recommend is called the I.D.E.A. model. The I.D.E.A. acronym takes you through four steps of thinking through your idea and presenting it in the most compelling way possible. I stands for “interesting”: Is the idea strategically relevant for the organization or the leaders that you’re sharing the idea with? D stands for “doable”: Do we have agency over this? Is this something we can take action on in the next six to eight weeks? E stands for “engaging”: Who are the other stakeholders who need to be engaged in this idea? And why would they want to be engaged? Finally, A stands for “action”: What are the next two or three tactical steps we would take to implement my idea? An idea that is vetted through those four steps is immediately relevant and usable. This gives it a much better chance of being implemented than if you were just presenting a loose concept.

Karin: Imagine going to your manager and saying, “I really care about our team, I care about our success, and I’ve got an idea that I really think will make things better. Here’s why it’s strategically interesting and aligned with where we’re headed. This is how we can pull it off. And here’s who else I’ve talked to about it and who also thinks it’s a good idea, and these are the people willing to help. And here are a couple of first key actions we can take to get started.” Your manager can’t possibly ignore such a pitch. Your manager may not use it, but they will certainly not going to think less of you for presenting an idea in that way. At the very least, you have built strategic credibility as a critical thinker.

How can middle managers start promoting a courageous culture within their small teams?

Karin: We talk a lot about building a cultural oasis. Even if you are not working in a very courageous culture, you can still create courage, generate ideas, launch pilots and try things out within your own team. In the book, I share a case study of my time at Verizon. I was leading a 2,200-person sales team at a very challenging time where we really needed great ideas. My boss at the time was very risk-averse. And yet, we were able to start small, try out some ideas, prove some things and eventually get a groundswell of momentum that was hard for anybody to ignore. The team ended up winning the president’s award for customer growth because we were blowing revenue targets out of the water. You don’t have to make a big announcement about things. You can begin small.

If everyone always agrees with you, you probably don’t have a courageous culture.

Karin Hurt

What kind of employee reward structures are the most conducive to creating a courageous culture?

David: Leaders often make the well-meaning mistake of creating an award for the best idea. The problem with only rewarding successful ideas is that you are not rewarding risk. The behavior you really want to reward is generating ideas that could work or that have a chance to work. Have people come up with ideas by acknowledging and thanking them also for well-thought-through ideas that you cannot implement. Those are the kinds of ideas you want to be rewarding because that’s the behavior you want people to embrace.

Karin: We also have a chapter in the book about building an infrastructure for courage. When measuring performance, what competencies are you considering? Are you evaluating people on their critical thinking and problem-solving skills, and on their willingness to speak up and contribute? Who gets promoted? Is it the people who are good at following rules or is it the people who come up with creative solutions, take some risks and try out new things? Because that’s what everybody is watching. You won’t create a courageous culture by always promoting the people who do exactly what the boss says.

About the Authors

Karin Hurt is a former Verizon Wireless executive, and an Inc. Magazine Great Leadership Speaker. David Dye is a former executive and elected official. Together, they founded Let’s Grow Leaders, a leadership and consulting firm. Karin and David are the authors of several award-winning books, including Winning Well: A Manager’s Guide to Getting Results – Without Losing Your Soul and Courageous Cultures: How to Build Teams of Micro-Innovators, Problem Solvers, and Customer Advocates.