“You’ll Be Surprised about the Cost Savings and the Motivation Boosts.”

John, big companies have been doing it for some time, and medium and small ones are following suit. They are setting up systems to identify internally available skills and talent and deploy them in a more targeted way, i.e., no longer just via classic job profiles. So where does the economy stand in this transformation, and why is it worth thinking about Work without Jobs?

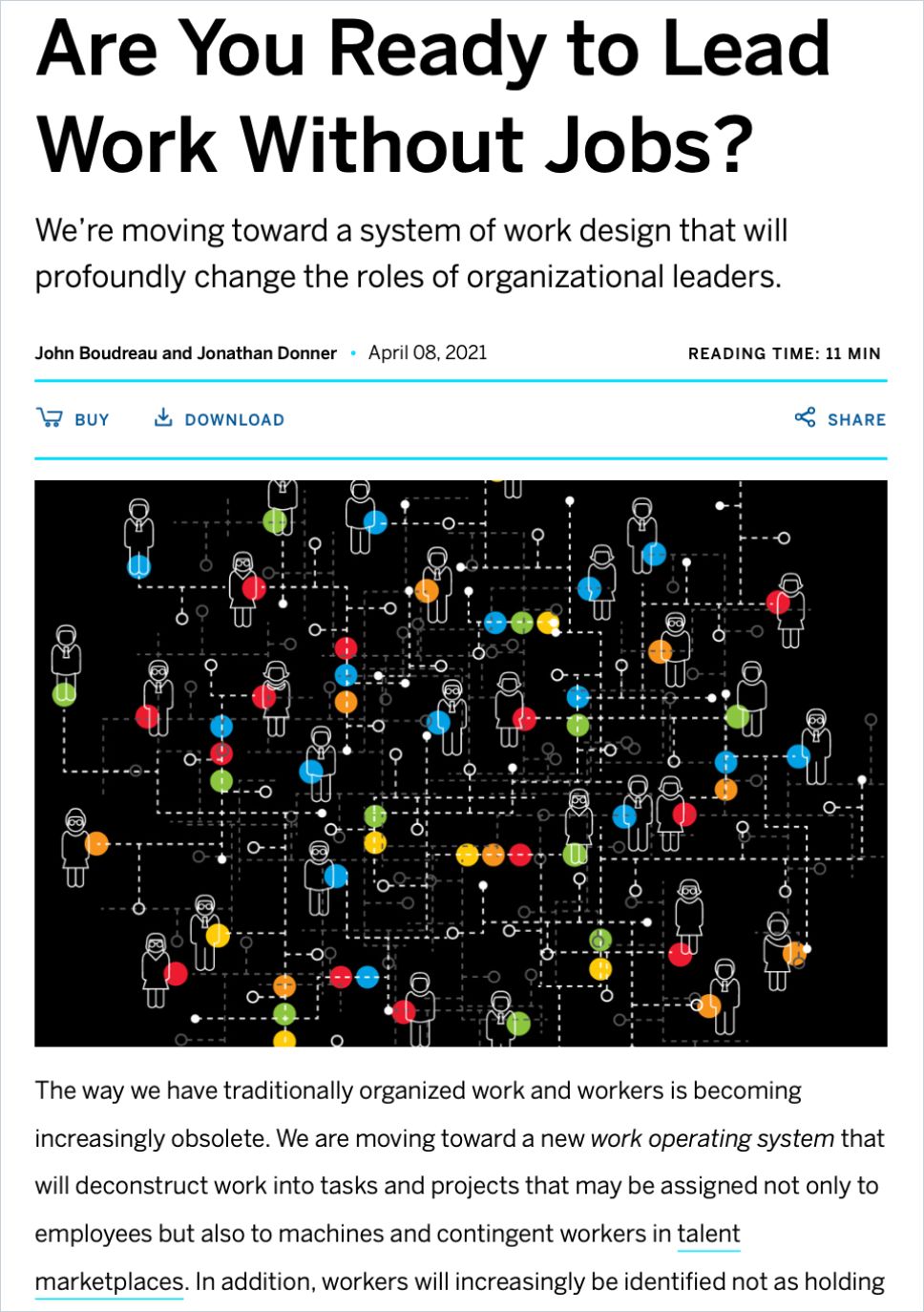

John W. Boudreau: Well, for the most part, I think the world still thinks of work as a job. Work equals jobs. Worker equals a job holder. And if you listen to policymakers and leaders talking about the future, they often talk about “more jobs,” “good jobs,” so we still measure economic health by jobs, too. The system worked for centuries, and for many companies, it still does. Basically, work can be symbolized as ice cubes; as of today, these are primarily standard square ice cubes standing for a job, a job holder and even a degree. They stack nicely regarding how we know if – and where – people are working or if they’re qualified.

But?

In more and more organizations, the standardized ice cube model reaches its limits because the “jobs to be done” are shifting quickly and can no longer be aligned with conservative job descriptions – or at least not in time. Over the last few years, I heard many HR leaders say that the classic job, job holder, degree ice-cube system gets in their way when things are changing fast, and this intensified with the current talent shortage:

We need people to be able to move to where the work is required, help each other out, and we might hear workers say, ‘well, that’s not my job.’

A way to cope with the frustrating situation is to allow those ice cubes to melt and then let the melted parts perhaps reconfigure in different shapes – or even remain melted. There’s a lot of opportunity and potential in thinking about more fluid work. Instead of an operating system built on the jobs, job holders and degrees, you may allow the system to work at a more granular level, allowing tasks and individual capabilities to match up.

In other words, more agile times need more agile working methods?

Exactly. There are many places where this fluidity emerges as potentially helpful. And agility is an excellent example, as it is one of the triggers that Ravin Jesuthasan, my coauthor and I identified in Work without Jobs: The standard work operating system is stressed and stretched because things are moving faster. Other stressors include the need for automation or multi-stakeholder initiatives around topics like Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). Sometimes, HR struggles with missing talent that cannot be found in time, particularly externally. They may even be unable to write a job description to reflect their changing needs. The same applies to the workers: They don’t know their next job in a fast-changing or new work situation because the operational requirements vary and change disruptively.

In addition, managers stick to silo cultures that presume certain workers ‘belong to that manager,’ because they believe they cannot reach their goals otherwise, and that limits sharing talent across managers. All of these cases result in things not getting done.

And ever more leaders, especially in HR and L&D, reach a tipping point where they say, “To get more agile, we must take the entire body of work and allow it to melt and reconfigure constantly.”

But when time and talent are scarce, isn’t that a bit too much of a good thing in the heat of the moment?

The basic idea is not that complicated. I often encourage leaders and workers to pretend they have a paper job description. Now, imagine it’s just about cutting it into strips, each strip of paper representing the tasks or projects within that job description. Do that for all the job descriptions in a work arena – such as a call center, distribution center, production line, retail store, etc. Then, put the pieces on a big table, and ask yourself: “How would you organize this work if it didn’t require you to contain it in jobs?” Of course, this works if you have some time for it. But even when it’s time-sensitive, you can “start with the work” by defining the needed work elements to reach a specific goal or get a job done, craft a short project description and search for internal applicants. That’s precisely what emerged in many companies when COVID happened. It continues today with internal talent marketplaces.

Do you mean a lot of unforeseen staff-sharing due to new necessities?

Yes. In fact, many organizations became accustomed to more fluid work systems during COVID, but most still hesitate to take bolder moves toward them. The fluidity emerged because it was needed, and there was no alternative. In many companies, the supervisors of the call center and the supervisors of a retail store learned that they had to share people because the workers from the store had to relocate to their homes due to COVID restrictions. Those relocated workers from the physical store could be set up at home to do call-center work. The managers figured it out, and by doing so, they took the first steps toward an internal talent marketplace.

Yet it happened under coercion during the pandemic. But, if I’ve got you right, stepping into a world without jobs is – from an organizational point of view – a deliberate decision. How does that work?

The basics are: Leaders are posting projects, and workers are free to take on those projects as they see fit, even in addition to their regular job. Very often, there isn’t a formal mechanism determining which projects they take on:

Today’s internal talent marketplaces work kind of outside and in addition to the traditional system. And in many companies, that seems to work: People are happy to volunteer for projects that interest them, and leaders are delighted to voluntarily post projects, rather than entire jobs.

Yet, over time these voluntary arrangements will expand into areas where people expect to be paid.

Likely. We already see more attention from works councils, unions, et cetera, saying, hey, wait a minute, isn’t this a way of exploiting workers to get them to do extra work? These days, internal talent marketplaces are experimental and emerge as needs emerge. In most cases, workers seem to find purpose in these new systems. They see upsides regarding their skill development or showcasing their capabilities that are not used in their regular job. They like engaging with other groups, having a different view and impact on things; these seem to be sufficient rewards. So, for now, a money discussion often isn’t necessary. A common rule of thumb regarding the limits or “red line” might be: “Stop taking on projects if they interfere with your regular job.” If these extra tasks increase significantly, then people might say, “This is like a second job. And yes, I feel good about the purpose, but it’s so much that I’m going to raise my hand or go to my works council and say we need some way to encompass this in our regular work arrangement.” That’s why I think there will be more formalization soon.

How do you convince managers of the new system?

I’ve talked to several companies and asked them, how did you get the managers to give permission for their people to take on this additional work? And they said, “We didn’t ask them. We just implemented it, and some people quietly started doing these projects and then their managers realized this could work.” So, why didn’t they ask the managers in advance? They answered, “As you might expect, they would have said no.” (Laughs.) So, the idea is that managers learn that the workers who report to them have the desire and capacity to take on these additional projects without reducing their effectiveness in the regular job. As these projects become more frequent, the project manager should have an overview of who has been working for them and keep track of that when performance is reviewed. Managers do not necessarily need to know about every project task their team members have accepted. But it is best if they come together periodically to be sure that they are working together as workers move fluidly between them.

Is the “talent crunch” accelerating the need for fluid work systems right now – or is the pressure around it more likely to cause HR and L&D people to lose sight of new solutions?

The difficulty of getting candidates for regular full-time jobs does accelerate a desire to find different ways to engage workers and new models to fluidly equip your workers for the future. Yet, shifting the demand curve instead of the supply curve might be a way to solve the problem. If you’re encountering, for example, a labor pool that is 80% qualified for the job you offer, and you say, I’m only going to hire 100% skilled people, that restricts the labor pool quite a lot. Then, you have a significant shortage. But if you could reconsider your job and fluidly and allow for building a slightly different job that matches the population with 80% qualifications, you’d have a bigger labor pool.

And the other 20%?

For them, you need to find a creative way to make up for that, perhaps training existing employees, or perhaps external gig workers, contractors – perhaps some volunteers from your existing workforce via a specified project. So, it may be worthwhile to step back and ask if perhaps the job description we’re asking for might be the issue.

Insufficiently qualified talent may not be your problem. Instead, it could be your work operating model based on jobs. Ask yourself: ‘What would it look like if we weren’t required to define the talent acquisition model as this job against a workforce that needs to be 100% qualified?’

Okay, let’s look closer: Not every company can afford a fancy software solution when setting up an internal talent market platform. How do small and medium-sized players proceed once they understand they can ease the pressure?

Platforms like Gloat, 8Fold, Hitch, Workday, SAP and others are getting more affordable due to more competition in the market and their comparably cheap additional features that replace expensive software suites companies had to pay extra before. Some organizations might already have contracts with learning companies like Udemy, Degreed, et cetera, and these are adding talent market platforms to their offer to take advantage of their unique skills taxonomy as well. So that might help get some started without paying too much extra. Yet, as far as I know, we haven’t seen very much formal integration with an entire HR system. Companies who hesitate to buy external solutions should imagine an internal talent marketplace similar to the known external freelance platforms but restricted only to people that are already employees and leaders. You can set this up by simply showcasing projects and positions through your intranet or collaboration software and let volunteers and project leaders take it from there.

So, if you want to try the new system and already work with software like Microsoft Teams or Slack, develop a channel for projects and have leaders and employees look at it regularly, post projects there and have talent apply for it?

Yes. You’ll be surprised about the cost savings and the motivation boosts. The CEO of Unilever, in his investor call, even put it in terms of the number of jobs for which they didn’t need to hire. He saw this as opening a formerly untapped, unseen, yet huge skill base by asking for internal project applications. I’m not sure I would always frame it that way because Unilever effectively communicates it to their staff not so much as labor cost savings but rather as upskilling options or following your passion and purpose. Yet, the reality is that some companies may not have to hire as many new employees because existing people find this extra time and volunteer for projects when they see their time is spent reasonably.

But why should skilled employees who likely already work at capacity volunteer for these projects?

For many siloed employees, talent marketplaces offer chances to break out and unleash their potential. For example, I remember reading an example of a person in a finance function at Unilever, who took on many diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging projects. That was their passion. And eventually, the formal diversity group put a job together for that person, and Unilever moved the person formally to that job because the person had shown their passion and did excellent work. Soon, if you add machine learning and an outstanding corporate skills database to the equation, there might be even more career paths opening up for them, which is another strong incentive to voluntarily take these chances.

So, if you have an internal AI-powered talent platform in place, you don’t have to write a project description anymore because the machine will write it for you?

Yes. The AI might even find the worker because it knows what their qualifications are! Some programs will also infer your adjacent skills or growth opportunities – just like a finance advisor bot does for many investors.

Via pattern recognition, AI can identify side skills or competencies for you as a worker, that might not be formally in your list of capabilities, based on how you are similar to others, and have those adjacent capabilities. It can then highlight new opportunities for you based on those inferred capabilities or skills.

Yet, if my company doesn’t have a reasonable database on skills and projects, even AI can’t turn rubbish into gold – and the job offers depend on it. Right?

Currently, most organizations won’t have enough information to train an AI independently. Yet, let’s think about a world marketplace of talent. I can envision it eventually working similarly to global product platforms like Netflix or Amazon: Based on many thousands of transactions matching workers to jobs or projects, the algorithm learns what best fits a particular worker. If you have much more anonymous data on general preferences, job qualities, and skill sets, put through suitable algorithms and compared with what you have internally, the outcome could be much more transparent and, in the end, much more worker-centric, worker-friendly than it is today. But, as you say, we’re not there yet. Today’s algorithms typically see only the data from one company.

Which department, thinking in terms of old standard ice cubes, should push this transformation forward?

The HR function is where companies seek skills, learning and employee capability expertise. What they should do, at a minimum, is create a comprehensive skills register that collects the skills available in the company. On the one hand, by asking employees about their strengths and abilities. On the other hand, ask colleagues and managers about the employee’s capabilities and possibly untapped potential. They should match the collection with what will be needed to remain competitive.

So, HR leaders are well-advised to watch and record what’s happening and transforming these days, at the level of worker capabilities. Together with L&D, they can modify their traditional skills inventory that is typically based on jobs and formal training, and evolve toward a more capability-based, fluid system.

Staffing is another function in HR where this can start. Staffing leaders have expertise in thinking about external talent markets in a way that a traditional L&D group might not have. Because past work on competencies and skills was often about progressions through jobs, those existing systems can be a bit clunky and inefficient. Shifting the mindset toward capabilities can improve them.

For instance?

A more fluid system is more about the concept of capabilities, something you can do, as distinct from a skill, something you know or have learned. “Skills” may be one level too specific. For example, “Speaking Spanish” can be a skill. But the capability that is needed might be whether someone can simultaneously translate a conversation or translate a written story. Each of those two capabilities builds on the skill of knowing Spanish but seeing the capability offers a better unit of analysis for matching a worker to a project or task.

The list of things to do when setting up an internal talent marketplace has filled up nicely. But what do you think should be avoided at all costs?

There are several pitfalls. From my perspective, the first “Don’t” would be attempting to do this where it’s not yet needed. Most organizations follow this advice pretty well because it’s such a big job to change the entire system. (Laughs.) If there are arenas of work where the traditional operating system works, then avoid forcing employees to become more like gig workers or freelancers and avoid forcing managers to think in terms of gigs and projects. Instead, aim your transformation effort at the places where the energy is already there, usually because something isn’t working quite right. As I noted earlier, this is often in arenas where you are implementing agile methods, automation, or where there are very qualified outside workers available as contractors or gig workers.

Second: Choose carefully where projects can be easily decomposed or deconstructed. This is why we often see such systems applied to arenas such as software development, call centers, etc., where organizations often have external freelance platforms as models, or where the organization has experiencing with outsourcing certain tasks or projects.

Third: Don’t be too eager to turn the projects into jobs. Sometimes that happens naturally. However, keeping things fluid once the ice cubes are melted removes a lot of transformational friction.

Fourth: HR should not go in alone. Changing the system from jobs to projects has implications for leadership, information technology, facilities, and other functions. Successful organizations see this as a cross-disciplinary organizational project from the start.

Fifth: Ensure you don’t rely too much on the software system. Avoid the temptation to say, “Well, we’ve implemented the talent platform now. We’re done.” The software is only one component of a much larger change effort to reframe work, and there will be a lot of teaching to supervisors, managers, and workers.

But, again, that’s a beautiful role for HR and L&D to play, teaching about fluidity and capabilities and helping to elevate the understanding of everyone involved.

About the Author

John W. Boudreau is a University of Southern California professor at the Marshall School of Business, and the research director of the Center for Effective Organizations.