“Structure Begets Flexibility.”

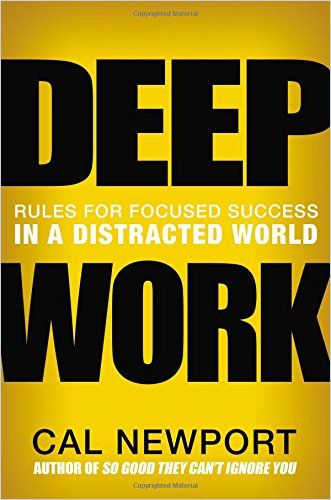

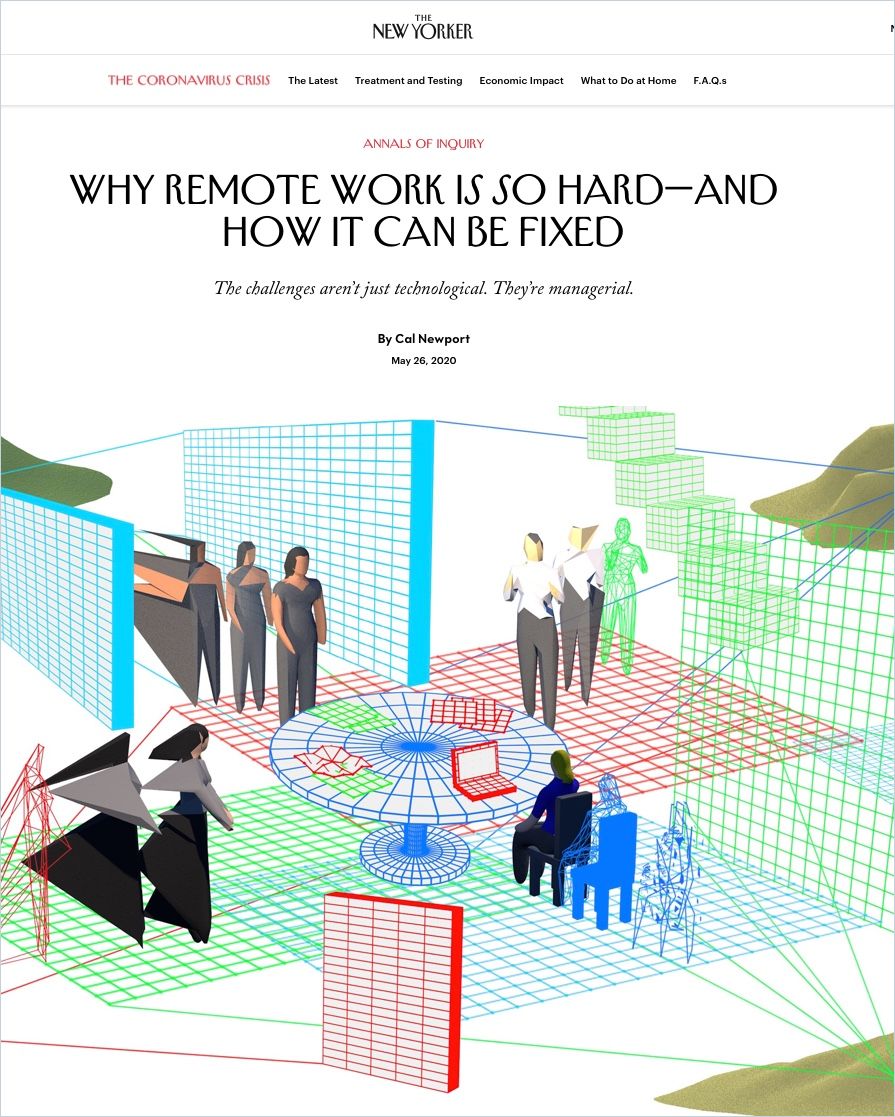

Cal, your modern classic Deep Work is from 2016, and it has only gained relevance in the five years since it came out. What would you like to say to everyone sitting at their desks in the second year of the pandemic, perhaps at home, but always somewhere between their children, colleagues calling, their email inbox and Facebook timeline, the boss and the mailman finally bringing toilet paper?

Cal Newport: One thing I would say is: The way we’re working right now is severely broken. If you feel very frustrated, if you feel like it makes no sense, if you feel like you can’t concentrate, you spend all day jumping between Zoom and Slack and inboxes, but nothing gets done: You’re not alone! And you’re not irrational. We will look back at this period and say this was a ridiculous way to organize knowledge work.

Why?

The key culprit here is that the human mind, the human brain is very sequential. It’s meant to do one thing after another with a relatively slow context shift between these actions. That’s the way our brain is supposed to operate. What we’re doing instead is entirely trying to fragment this experience by putting on dozens and dozens of things simultaneously. That might work for computer processors but does not work for the human brain.

We’ve taken the most valuable resource that we have in knowledge work, the human brain, and put it into the absolute worst setup of a work environment. So, if you feel incredibly frustrated, you are right to feel frustrated.

Cal Newport

Could it be that our constant multitasking over an entire year is now a reason for the current “corona fatigue” that many companies, and especially their employees, struggle with? What can one do about it?

Yes. The productivity poison in this scenario is context. If you change your cognitive context to something else, it triggers a whole cascade of neurological changes. That takes a long time, sometimes up to half an hour. If you, for example, check your inbox briefly, maybe just a few seconds at a time, because you’re waiting to hear back from your boss as you’re trying to schedule a meeting and need to play ping pong right back when he answers, this seems innocent. But it’s not. At least not when you’re working on something else that matters. You initiate a context switch in your brain, and then you abort that context. When you try to go back to the original cognitive context, after ping-ponging, refocusing on what you’re actually working on, these tasks collide. It creates a significant reduction in your mental capacity. And if we now assume that it’s not just the one inbox, but also the cell phone, the team chat, the knowledge base wiki, maybe your kid barging in – it’s simply impossible to keep a clear head in this environment.

But do we have an option? I mean, we all were forced to leave the offices, which weren’t perfect either, due to the pandemic. And in some way, we’re pretty proud that this worked. Many executives are still surprised at how productive everyone is in their home offices. They spent years and years telling us that more remote work wasn’t possible. But it is.

I would push back on this idea that we’re more productive if we’re trying to measure what matters: valuable output. What a lot of managers mean when they say, “Oh, I’m surprised we’re productive,” is: “OK, there’s still a lot of performative, visible busyness that occurs all day long, even if we’re not in the office.” But that can be pretty orthogonal to “Are we producing the things that move the needle on our company?”

Point taken, but after all, we have only taken the first steps. What should we pay attention to now that everything is “up and running”?

The real issue is: Unbroken concentration is valuable, and we still underestimate it. We should protect it. After Deep Work came out in 2016, and I argued for carving out times when you are not available and not distractible, I got a lot of pushback from people who said, “You don’t realize how impossible it is to do this!” Since then, I have tried to understand why that’s the case and we work this way, and how we could restructure the world of work in a way that makes deep work possible. One of the big ideas that came out is that knowledge work is obsessed with autonomy. We leave people alone to figure out how to organize their work and get things done. We think productivity is a personal thing. “If you’re stressed out, just buy some productivity books and get used to it…”

You mean: We put the cart before the horse?

Exactly.

We never asked the right questions. Instead, our supervisors told us: Look, everyone can talk to everyone. We have a lot of high efficiency-low friction communication tools, rock ‘n’ roll! Here’s email. Here’s Microsoft Teams. Just figure it out! In that environment, we’re never going to get out of this issue of constant distraction and pinging.

Cal Newport

Because we fall into this lowest common denominator where everyone grabs everyone whenever they need it for anything. After all, for each person, that’s what’s most accessible at the moment. I hope that this temporary period of forced remote work will give us a sense that we have to start getting serious about the structure of work. We have to get a lot more thoughtful about how we want to structure work, how things are identified, how they’re assigned, how collaboration happens, how we review it. Because right now, we’re just in this hyperactive hive mind of constant out-of-control communication that makes almost anything impossible.

But, in a running organization, whose task is it to tackle this?

Well, it can’t just be left to the individual anymore. And I think the fitting analogy here is to think about the industrial sector. The way we used to build cars, for example, was – for a long time – very flexible and convenient and intuitive, sort of the way we work now. Here someone screws on a wheel, there someone still has a screw, now, let’s find out where the windshield is. But it turned out that this is not a very effective way to build cars. It’s pretty slow and requires a lot of workforces. It has a lot of rough edges. And then, Henry Ford came around and figured out the continuous motion assembly line, which was 10 to 100 times more effective to build cars. In the beginning, it seemed complicated and a pain to get right. It required more overhead, more systems, and processes. But it turned out to be the right way to do things. Something similar has to happen in knowledge work. To spark this change, individuals can do things right away to protect their time of unbroken concentration:

Reduce the number of unscheduled messages, for example, or close Outlook for a while, mute your smartphones when working on something. But ultimately, we have to move as organizations and teams away from this productivity model as personal, and take responsibility for how we want work to happen in our company.

Cal Newport

What are the concrete questions to ask – and to be answered?

How many things should we be doing at the same time? How should those things be chosen? Where is the information you need for those things when you need help from other people? When does that happen? We need some structure, and the answers depend on the individual organization and its teams.

This is going to lead to a productivity explosion!

Cal Newport

It’s going to make people much happier, and it’s going to make work much more sustainable. Like in the industrial sector, that first leap is hard because this new way of working is not as “easy” as what we do right now. So, for starters, have a conversation with your boss or supervisor to explain your work, why it’s flawed to some extent in the current environment, and why you want to do things near the peak capacity to thrive. Explain that you could produce much better results, much faster, if you can work without distractions. Define with him the ideal ratio per week when it comes to deep work versus shallow work. The answers will be different, depending on your job, but at least you nailed down a question, got an answer, and everyone involved has to deal with it. I’ve heard case after case where this positive and measurable conversation leads to significant changes.

Are we talking about hours or days of paid unavailability here?

Two hours in the morning, two hours in the afternoon is not an unreasonable thing to ask for. I know a company that does no communication before noon three days a week. And that is the time where you can do work without having to check all the context. You have no meetings, no expectations of answers. This stuff is a lot closer than we think. It’s just we lacked the vocabulary to get to it. And boom, things you felt are entirely entrenched cultures that never change could change almost overnight.

What do you think of the currently popular idea of having at least one “no-Zoom day” per week?

First, we do way too much Zoom – yes. One of the reasons for this is that we use these meetings as a proxy for productivity. “I have to make progress on this. I don’t trust myself to do that. So, here’s what I’ll do: I’ll set up a meeting with other people because the one productivity tool that everyone trusts is their calendar. If there’s a meeting on their calendar, it will make them feel better at the moment. So, why not talk about this each week…?” And you multiply this among many different responsibilities. That’s when you get way too many Zoom meetings. When you’re in an office, at least, there’s a higher cost of setting up a meeting. You have to sit there in a room and see these people who had to get up, get their coffee, get their notebook to come into the meeting room, and look at you.

There’s more of a cost of setting up a meeting in the physical office that we didn’t do quite as many of them. But forget ‘no-meeting days!’ Instead, there should be no-meeting parts of every day.

Cal Newport

When is the best time to set them up?

I think virtual meetings should be relegated to a few hours in the afternoon. This time is more of a scarce resource. So, there’s less time available for these meetings. And recently, I’ve been advocating for reverse meetings. I think everyone should hold office hours at certain times every week where they’re just available. They’re in a Zoom room. You can come and grab them. If I need to talk to a group of people about something instead of me gathering all of them into a Zoom room for one meeting where everyone talks for 10 minutes, I should rather have to go to each one of their office hours and speak to each of them for 10 minutes. This way, you reverse the meeting: The person who wants to hold the discussion now has to do more work. It works out to have significantly less impact on individuals. And, as I already said, these meetings need to be more structured: Here is how work happens, nailed. Here’s how we assign tasks, nailed. Here’s how many tasks you should be working on, nailed. Here’s our structure for how to collaborate, nailed. We’ll need many fewer meetings, and the panels themselves have to be much more structured.

Is it worth separating internal from external communication? In other words, to specify, for example, that internal communication only takes place via a team chat software, and to use email “outbound only”?

Yeah, I think being much more careful about what we use each tool for can make a big difference. I like that. I like the rules. Email, for example, is great for broadcasting information. “So, here is the new production schedule for next month. Here is a new regulation.” But email is bad for conversation. If I have to interact with someone to figure something out in real time, the conversation needs real time. Use Teams or Slack for it! But neither team chats nor email, for example, are a good repository for information on a project.

You mean: A knowledge base is not a chat?

It should be in some other type of third-party system. Use this, and only this, for all the organizational information about projects, clients or objectives. All the files are there, and they should not coexist as emails, in Slack, or anywhere else.

Ask: What role do each of our different tools play? That is how to get away from the current hyperactive hive mind, making communication as fast as possible and as little as possible.

Cal Newport

I’ve recognized that I use email less and less since everyone’s on the team chat software. It made my structured work much more manageable, indeed. But what could replace email?

Yeah, I mean, these are all the same. (Laughs.) My new book, A World Without Email, is a follow-up to Deep Work. The real culprit in both, the villain, is what I call the hyperactive hive mind workflow, which is where we just figure things out on the fly with unscheduled messaging. Initially, the email made that possible. It became prevalent in the 1990s because it solved many real problems: It replaced the fax machine, replaced voicemail and replaced interoffice memos. It was a much better solution than those. But email was only the first of many new and popular tools that make our hyperactive-hive-mind-collaboration even faster and even easier. So that’s what Teams does. That’s what Slack does. But they’re all supporting the same flawed workflow where you have to check those channels constantly. It’s not because you’re addicted to email, and it’s not because of a lack of willpower. It’s not because you have bad habits. It’s just because these unexpected conversations are how all of the work is happening. And if you don’t check in on these channels, stuff grinds to a halt.

So how do you get rid of the hyperactive hive mind?

Well, it’s not with a tool. It’s with better structure. It’s with better processes. It’s with better rules and guidelines and systems. That is the solution to this issue. It’s not a tech solution. It is a work processing solution. We’re not missing some magic technology that makes smarter work possible. Instead, we have to use the existing tools more reasonably. They can play a crucial role in a very highly structured workplace. Just put some honest thought into it! The same applies to the office, by the way.

Over the past year, we’ve seen how the places we’re supposed to focus our attention have been mixed up. It looks like this is a prophecy of the future “hybrid workplace” – with all its pros and cons. What do you think of this “more flexible” split between office and “elsewhere”?

The hybrid workplace world will open up a lot of opportunities for people. It will open up colossal talent pools for companies when you no longer have to compete for the same talent in the same metropolitan area. To manage our days in this new environment, I think we can learn from the one sector that has not had many problems with remote or hybrid workplaces historically: software development.

Why don’t they have the issues we’re facing?

For other reasons, they have highly structured ways to organize their work. Most of these teams use some agile project management methodology. They have shared task boards that clarify all the different tasks being worked on, who’s working on what, what its status is. They have very synchronized ways for how they check-in and update these tasks. They think a lot about how to organize and collaborate. It’s not that hard for, let’s say, half of a software team to be remote or everyone to be remote. You can be very flexible in terms of where people are and what’s happening when you’re structured.

It seems counterintuitive, but structure begets flexibility: The more structure you have around how work happens, the more flexibility you could have in terms of when and where that work happens. We, as knowledge workers, have to take a page out of that book for us.

Cal Newport

About the Author

Cal Newport is an associate professor of Computer Science at Georgetown University. In addition to researching cutting-edge technology, he also writes about the impact of these innovations on our culture. Newport is a New York Times best-selling author of seven books, including A World Without Email, which argues that we need to radically reimagine work to move past the tyranny of constant communication; Digital Minimalism, which argues that we should be much more selective about the technologies we adopt in our personal lives; and Deep Work, which argues that focus is the new IQ in the modern workplace.