Building a More Equitable Future

Digital transformation affects every area of life and work, yet technological progress has not been equitable or inclusive, as a Microsoft map of areas in the US without access to broadband internet service vividly illustrates. Contrary to popular belief, technologies are not inherently neutral. Technology plays a role in everything, from work to shopping, school, research, communicating with each other, and even receiving medical help. As machine learning and algorithms become more ubiquitous in everyday life, business leaders must ensure their companies do everything they can on an ongoing basis to squeeze out inherent and historical biases in their processes, so they don’t perpetuate discrimination into the future.

Unquestioned Biases Perpetuate Discrimination

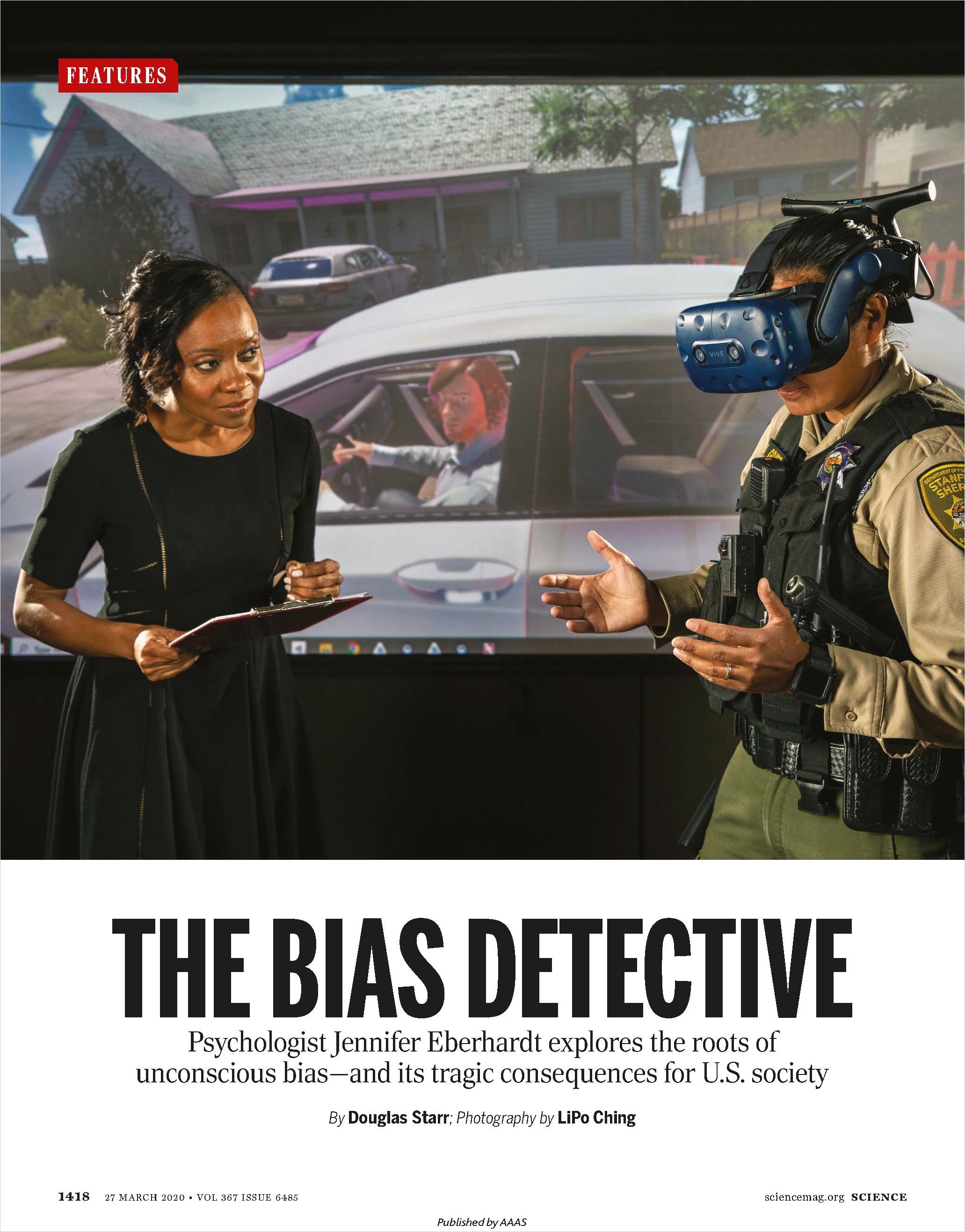

People are hardwired to make snap decisions, and categorizing people as “other” because they are different in some way is one of the earliest unconscious decisions humans make. But, Douglas Starr reports in “The Bias Detective,” it is possible to change inherent biases by becoming more conscious of them. Persistent discrimination in policing compelled psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt to delve into the cognitive basis for deeply ingrained biases.

Eberhardt used her findings to train the Oakland Police Department in techniques that greatly reduce disparities between white and black interactions with law enforcement.

There’s no easy antidote for unconscious bias. The legacy of past policies, such as segregated neighborhoods and mass incarceration, creates conditions that trickle down to individual brains.

Douglas Starr

Lack of Access to Technology and Training Disproportionately Affects Communities of Color

The COVID-19 pandemic proved internet access is vital now to both commerce and daily life. Yet, the digital divide between black and white in the US only grows, prompting researchers at the Aspen Institute to ponder in “Connecting the Last Billion” whether access to the internet should be considered a human right. In the 1980s, the US government set aside a part of the spectrum – WiFi – for free access to all, but then allowed telecoms to pay hefty prices for licenses to block the signal, forcing all to go through them to connect to the internet. The authors argue that “connectivity is education” and if government considered the internet a public utility, its value would be measured, not by the price of licenses, but by how much commerce it enables.

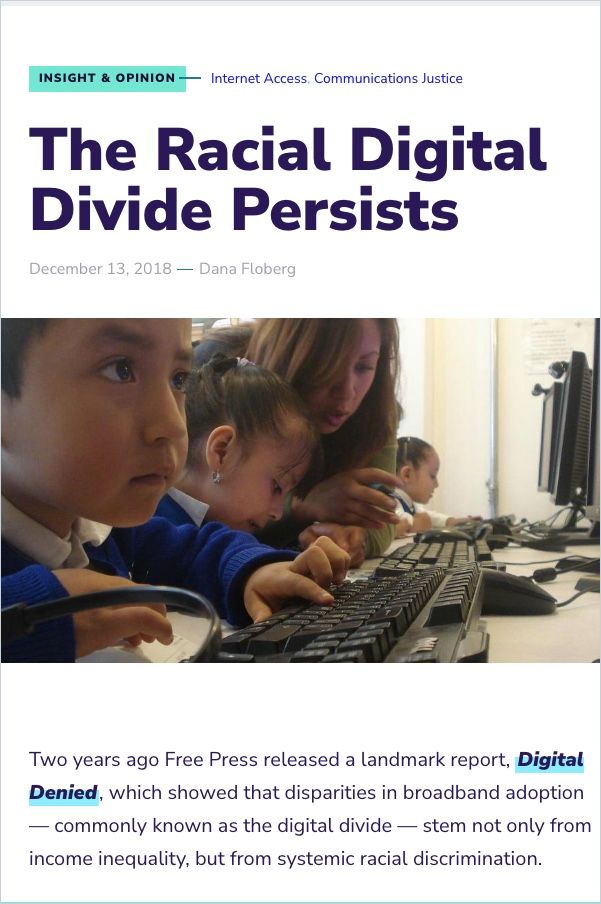

Research into the digital divide usually analyzes an urban versus rural split. But income is the largest factor when it comes to internet connectivity, and low-income households are disproportionately black and Hispanic. Higher costs and credit checks are barriers to internet access in these communities. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) made the problem worse by deregulating the industry in a way that allowed internet service providers (ISPs) to reduce competition and monopolize the market. It’s an example of the entrenched, systemic racism that keeps a racial digital divide in place, writes Dana Floberg, the associate director of broadband policy at Free Press.

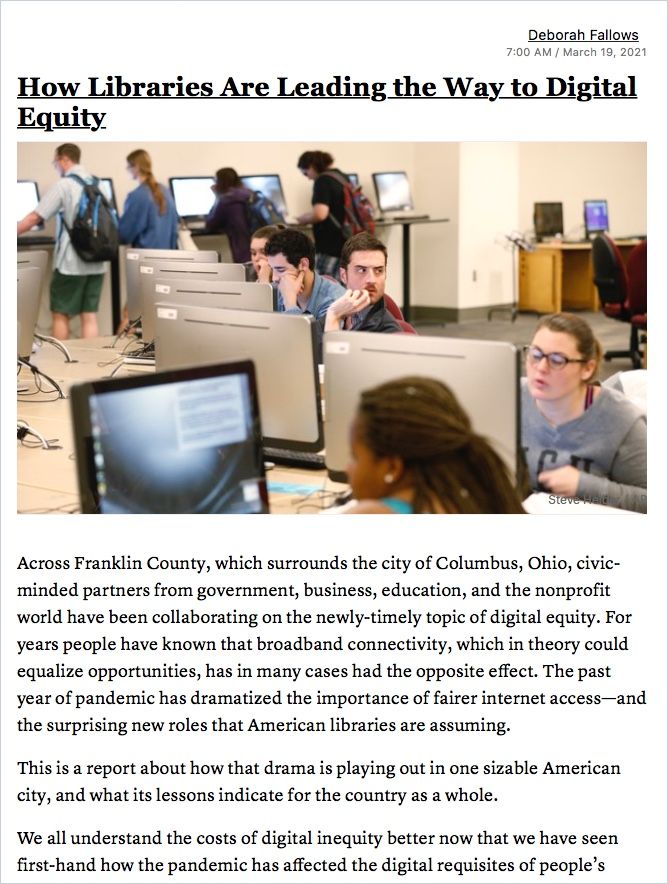

As journalist Deborah Fallows shows in “How Libraries Are Leading the Way to Digital Equity,” public investment in digital literacy and access to technologies – not only computers but also, for instance, 3D printers – lifts all boats. Fallows emphasizes the human infrastructure that makes libraries such vibrant community hubs also needs investment:

Library staff can do much more than recommend books – they can connect people with resources they didn’t know existed, showing them databases, subscriptions, interactive courses they can take for training or certification.

Deborah Fallows

Algorithms Have Biases Too

Digital technologies are accelerating the pace of change. But, as Sara Kupfer reports in her article “Robots Need Bias Awareness Training, Too,” artificial intelligence is only as impartial as the humans coding it. Authors Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Kleinsay point out in Data Feminism that the people who design algorithms are not diverse groups. This unintentionally perpetuates existing privilege and bias. Collecting massive training datasets is a capital-intensive undertaking done most often not just in the service of science but also “surveillance and selling” and, in the aggregate, does not adequately address diversity, equity and inclusion goals.

However, data projects in the hands of groups interested in broader goals of equity can effectively challenge the status quo. The Detroit Geographic Expedition and Institute (DGEI) used a visual mapping tool to locate where multiple black youths were hit by cars commuting from white suburbs, so those in power would address the issue.

Once a system is in place, it becomes naturalized as ‘the way things are.’ This means we don’t question how our classification systems are constructed, what values or judgments might be encoded into them, or why they were thought up in the first place.

Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein

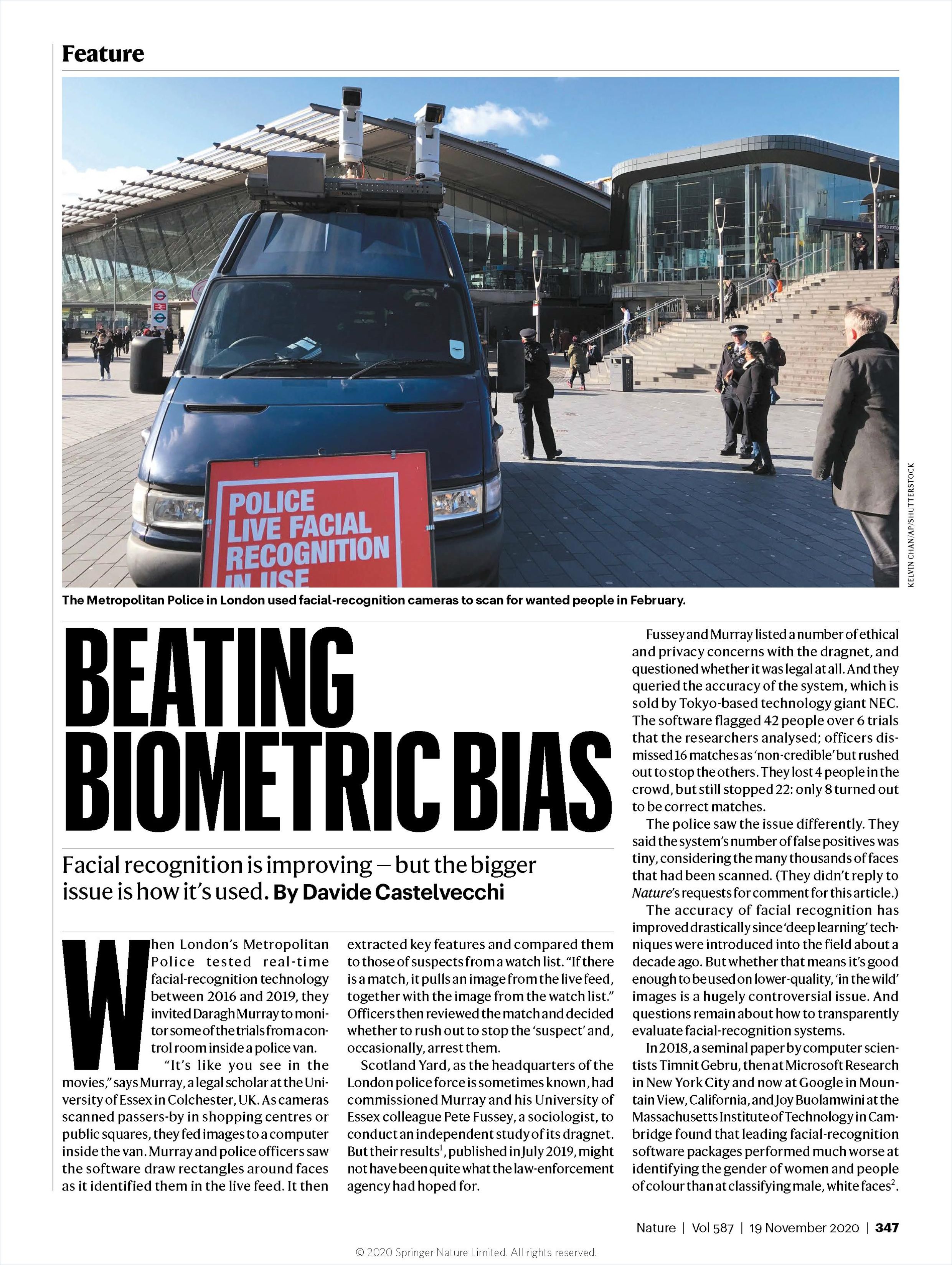

In a Nature article, “Beating Biometric Bias,” the authors note built-in biases in facial recognition software. Studies show biometric software misidentifies people of color and women more often than white males. So long as that’s the case, organizations shouldn’t rely upon them to provide accurate information.

Software is only as robust as the database used to train it. Oftentimes, the faces used to train facial recognition programs were captured without people’s consent, which raises other ethical and privacy questions. Misidentifications from biometric software already lead to false arrests. China uses its facial recognition technology to identify people who belong to religious minorities in order to persecute them.

Technical standards cannot stop facial recognition systems from being used in discriminatory ways.

Antoaneta Roussi, Davide Castelvecchi and Richard Van Noorden

Can AI Solve the Problems AI Perpetuates?

Authors writing for MIT Sloan Management Review say yes. In “Using Artificial Intelligence to Promote Diversity,” teams with a commitment to diversity and inclusion can create fairer, more accurate algorithms. However, even the best intentions can’t make up for biases inherently represented in datasets that algorithms use for training. These kinds of biases routinely cause algorithms to assume that nurses are women while men are doctors.

Using Artificial Intelligence to Promote Diversity

MIT Sloan Management ReviewCould more leaders of color in tech jobs solve the problem? Currently, nearly all employees of color are forced to deal with bias. As author Susanne Tedrick notes in her youth-oriented self-help guide Women of Color in Tech, women of color entering tech fields declined by 13% since 2007. Meanwhile, having to deal with microaggression, wage inequities, office bullying or tokenism in a white male-dominated sector discourages many black women from pursuing tech careers.

Yet increasingly, every sector is a tech sector, so Tedrick advises readers to keep up with emerging technologies and their applications and invest in maintaining a robust support network of colleagues and friends. As tech journalist Jasmine Henry writes in “Biased AI is Another Sign We Need to Solve the Cybersecurity Diversity Problem,” diversity in your development, coding and training teams can help troubleshoot technological blindspots that perpetuate human bias.

Using Artificial Intelligence to Promote Diversity

MIT Sloan Management Review Read Summary

How Algorithms Can Diversify the Startup Pool

MIT Sloan Management Review Read Summary