Learning Myths Debunked

Business leaders realize they will need to invest in continuous learning to keep up with the pace of change. Companies with a learning culture are more agile when facing challenges. Despite a commitment to learning, many people still hold erroneous ideas about how best to learn. Here’s a primer to put some old ideas about learning to rest.

Myth: You Only Have So Much Aptitude and Talent

People with “fixed” ideas about their learning ability feel frustrated when faced with unfamiliar material. One of the biggest myths about learning is that intelligence is a fixed quality. It’s not. Experts find no correlation between IQ and chess expertise, for instance. In fact, those with lower IQ do better because they practice more. As psychology professor Carol S. Dweck delineates in Mindset, the best learners have a “growth” mind-set, rather than “fixed,” which means they’re open to new ideas and believe they can improve their knowledge and skills.

People with “fixed mind-sets” view failure as a demoralizing obstacle, while people with a “growth mind-set” use failure as an opportunity to hone their skills and improve. Instead of dreading learning new things, they embrace the challenge.

The passion for stretching yourself and sticking to it, even (or especially) when it’s not going well, is the hallmark of the growth mind-set.

Carol S. Dweck

Myth: Everybody Has a “Learning Style”

Perhaps the most widespread learning myth is that every student has a learning type: “visual, auditory, reading” or “kinesthetic.” As journalist Olga Khazan lays out in her Atlantic article “The Myth of ‘Learning Styles,” this was the conclusion educational professional Neil Fleming came to in the 1990s. The idea that adjusting the presentation of material to correspond to a student’s preferred style would improve their comprehension caught on around the world before experts started to debunk it.

While it’s true that people have different preferences about how they get their information, little evidence exists that catering to these styles improves learning outcomes. Instead, there’s evidence that people learn best using the style they’ve always used to learn. Another variation on “learning styles” is the notion that some people are “left-brained” versus “right-brained” learners. In fact, everybody learns with their whole brain. Different areas are engaged during different activities, but the right and left hemispheres do not dictate a learning approach.

Truth: What Matters Is How Content Is Organized

The way learners organize information in their mind determines how well they’ll remember it say the authors of How Learning Works. It also determines how well they’ll apply what they learn, which is the most important result.

By “chunking” material into smaller pieces for periodic review, says author Barbara Oakley in Mindshift, then allowing yourself time between lessons for the information to be absorbed and applied, you build a mental representation or “mind map” of your field of inquiry, one that you can add to while you continuously improve your knowledge.

“Learning that makes an impact on the brain often means going just a bit beyond your comfort zone.”

Barbara Oakley

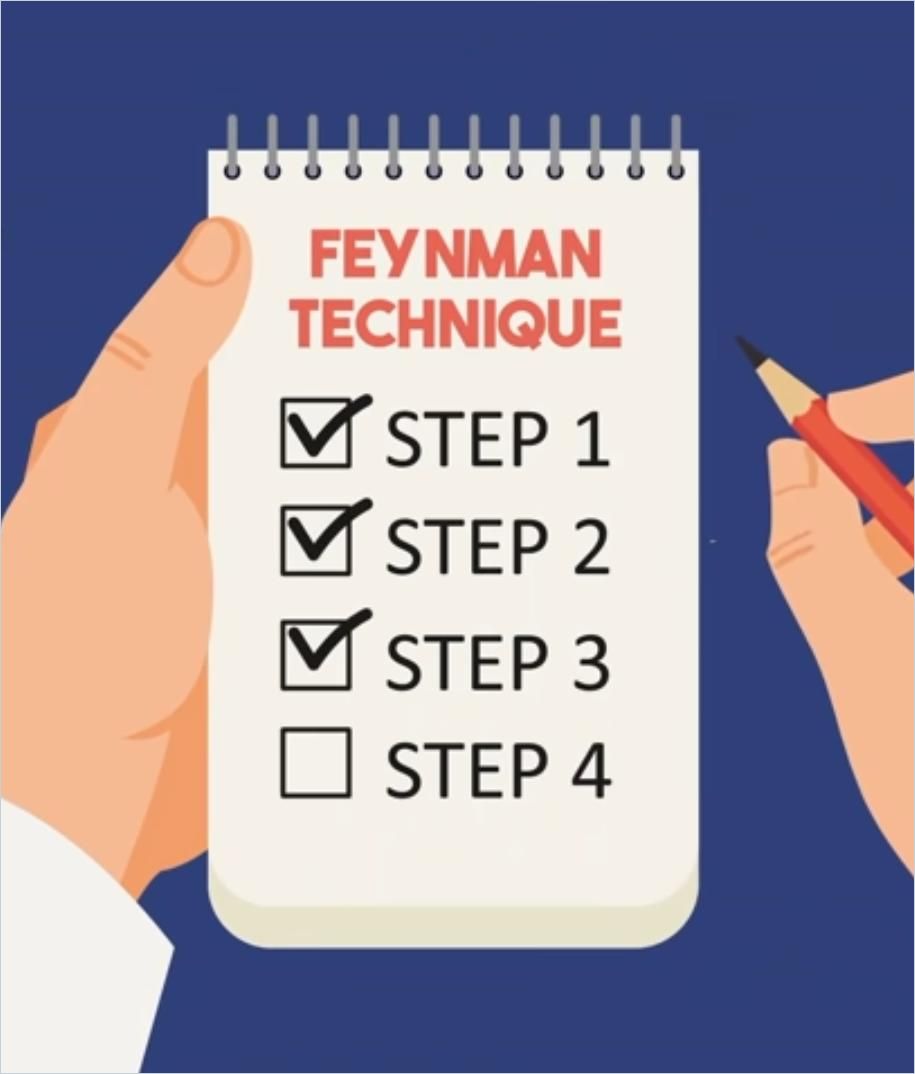

Physicist Richard Feynman’s learning technique, described by Tristan Reed, starts by writing down your existing understanding of the area you intend to study, which engages your brain. It also helps you identify gaps in your knowledge.

To truly understand a topic, you must teach that topic to someone who knows nothing about it, someone with zero background on the subject that you’re discussing. If you can’t explain that subject to a complete amateur, then there are gaps in your understanding.

Tristan Reed

Myth: Amateurism Is a Bad Thing

Unfortunately, human nature resists learning new things, especially if they contradict entrenched viewpoints or make you feel clumsy and amateurish. People don’t want to revisit novicehood after putting in the time and effort to achieve a high level of expertise. However, along with the innate resistance to starting fresh is an equally powerful urge to master new skills.

Additionally, for a long time, a now-debunked theory of human learning assumed that people had a finite number of brain cells that died over time, making it more challenging to learn new skills as they age. Instead, researchers have proven that the human brain has a lifelong capacity for learning. So the challenge is to surmount your resistance to being bad at new skills first and embrace the discomfort of being a beginner.

Getting curious is essential to learning because, when combined with aspiration, it creates an unstoppable momentum of discovery.

Erika Andersen

Michelangelo continued learning and taking on new challenges until he died at 88! He’s a prime example of a high-powered learner, and he is the embodiment of the four skills in the ANEW model of mastery:

- Aspiration

- Neutral self-awareness,

- Endless curiosity and

- Willingness to be bad first

The model was developed by executive coach Erika Andersen and codifies the powerful human drive to master something, even when it means “being bad first.”

Myth: 10,000 Hours of Practice Will Make You an Expert

In Outliers, author Malcolm Gladwell posited the “10,000-hour rule” – that in order to become expert at anything, you need to put in about 10,000 hours of practice. However, according to authors Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool in Peak, it can’t be just any 10,000 hours, and also, that number is a bit arbitrary. It matters what the subject is – concert pianists generally put in 20,000 hours before they start winning competitions – and it matters how you practice. You can play golf every single day and never actually improve, or you can do what golf champion Tiger Woods does: Figure out a program of “deliberate practice.”

To improve your knowledge or performance through “deliberate practice,” hone in on exactly the part you’d like to improve and focus on that. Pianists practice different parts of a piece they’re working on. Woods works on specific aspects of his golf swing. In any practice, you will hit plateaus. If a typist trying to improve speed recognizes they keep making mistakes with “ol” words, they will drill typing sentences with lots of “ol” words to improve performance. Through this thoughtful process, you develop better mental representations to call upon.

Keep in mind three Fs: Focus. Feedback. Fix it. Break the skill down into components that you can do repeatedly and analyze effectively, determine your weaknesses, and figure out ways to address them.

Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool

Truth: Use It or Lose It

London cabbies have such encyclopedic knowledge of the city’s streets and byways that it enlarges the area of their brain that stores spatial mapping information. When they retire, this area actually gets smaller from disuse. All top achievers know they need to keep applying their skills to keep them sharp.

Top performers like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett set aside approximately five hours weekly for continuous learning, according to author Michael Simmons in his article “5-Hour Rule.” To them, knowledge is their most valuable asset.

They follow these six guiding principles:

- Follow technological trends to identify the most valuable knowledge and skill areas in the near future.

- Identify the mental models that best help you assimilate new knowledge.

- Hone your ability to communicate your knowledge and skill.

- Convert your knowledge into value for others, for instance, a job.

- Invest in continuous learning.

- Leverage those few hours per week to maximize your lifetime learning potential.

Build a learning culture at your organization by emphasizing continuous learning in an atmosphere of psychological safety:

Learn more in our channels: