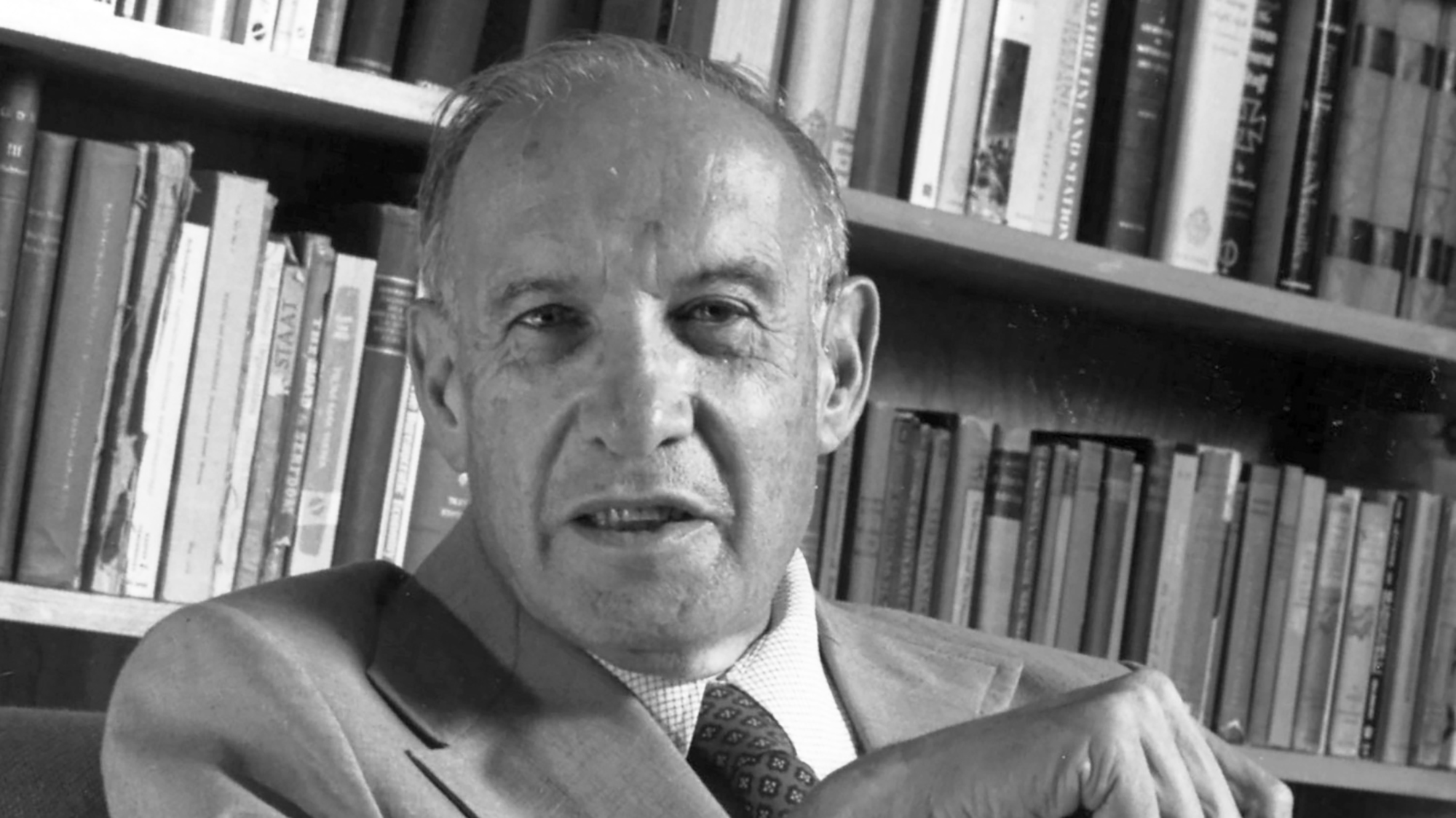

Lessons from the “Einstein of Management”

Peter Drucker’s life reads like a novel: He grew up in Vienna as the son of an upper-middle-class Jewish family. He went on to study at the universities of Hamburg and Frankfurt, where he graduated in law and history. During this time he became editor for international relations and economics at the Frankfurter General-Anzeiger, and received his doctorate in 1931.

After the Nazi regime put one of his early works on the list of books that were publicly burned on May 10, 1933, Drucker emigrated to Great Britain. He worked in London as a securities analyst and for the Financial Times, moved to the United States and became a professor of philosophy and politics at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont. He grappled with his own history and profession, and as early as 1939 the resulting book The End of Economic Man was published, in which he attempted to explain the phenomenon of fascism with an existential philosophical approach.

Impact

Drucker searched for a deeper understanding of the effects of modern industrialism. The meanings, threats and challenges of the rapid expansion of the industrial economy especially intrigued him. He came to believe that the big corporation was the single most powerful institution of modern society.

Peter Drucker identified corporate professional managers as a new major leadership group.

Initially, he approached his subject more as a political philosopher, since there was no field of management, but his early writings paved the way for him to build the discipline of management. As he described in The End of Economic Man, he firmly believed in the superiority of capitalism. However, he felt that for it to survive, it needed effective approaches to the unemployment, class conflict and social alienation the system produced. He urged combining economic pursuit with ethics and a concern for the larger community.

During his long lifetime, “the founding father of the study of management” published 34 major works, including 15 on the art and science of enterprise management. He became the most influential thinker on business and management in the world.

The Key Take-Aways of Drucker’s work

- Serve the customer – “The purpose of a business is to create and serve a customer.”

- Act, don’t just talk – Management takes hard work, sweat and practice. “Plans are only good intentions unless they immediately degenerate into hard work,” Drucker wrote.

- Ask the right questions – Drucker made complex matters simple by asking probing questions to drill down to the essential issues.

- Bring the outside in – Corporations tend to be insular and self-involved. The leader has a duty to make certain that people inside the company focus on the outside world, where the customers and competitors are.

- Focus on people – Drucker treated others with respect, and he lived the cliché that people are a business’s most crucial asset. “Management is about human beings,” he wrote. “Its task is to make people capable of joint performance, to make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant.”

- Results are what matter – Drucker’s favorite expressions included, “Don’t confuse motion with progress.”

But Peter Drucker not only has clear advice in store. He was also the first to shape the use of words used in everyday business today. Here is a small glossary of his management insights on current topics.

1. Common Knowledge

People are usually surprised when common knowledge fails them. Why, if they’re doing what everyone has always done, have they fallen flat on their faces? Peter Drucker found out: Usually the problem is that they acted upon outdated assumptions.

So, rather than guessing, focus on realistic possibilities. Then think through your options. If your sales start to decline, find out why. If they go up, do the same. Success requires connecting the dots. However, don’t change simply because you feel the need to do something. Be systematic and analytical. Once you’ve decided on a new direction, be bold. Don’t be afraid of adopting new approaches, fresh ideas and radical methods.

2. Economic Performance

Drucker believed that his era’s fellow management people’s focus on economic performance was too narrow. He urged large corporations to take more responsibility for the quality of life in the larger society. He saw the company as “a social and political system as well as an economic organization.” And, well, their managers as the key lever to make things better for all.

As an executive and a knowledge worker, you represent a highly valuable – indeed, indispensable – resource. Society depends on you, and millions of knowledge workers like you, to be maximally effective. If you are effective, your organization can be productive and make important contributions to the general good. Purposeful, efficient organizations can serve as “useful tools” to make life better for all. This is an enlightened and noble purpose. But society cannot achieve this vital goal if its organizations are ineffective. To avoid that pitfall, they require strong knowledge workers – and you are the one who can train them.

3. The “Three Time Zones”

Drucker pointed out that every business exists in three time zones – the traditional zone, the transition zone and the transformation zone, which correspond to the past, the present and the future.

The traditional zone is the status quo; the transition zone refers to what one is doing right now; and the transformation zone refers to building one’s business for the future. From his perspective, you need to strategically regulate all three sections at the same time so you can plan today for tomorrow. As Drucker put it, there are “no future decisions, only the future of present decisions.”

4. Change Management

Drucker welcomed change when others did not. After World War II and during the 1950s, most US companies preferred continuity. They allowed minimal, if any, change. Drucker argued that managers’ desires don’t matter. They had to deal with the acceleration of change because it was inevitable.

He said that once they managed basic business elements – and that included knowing about the market and using capital assets productively – they then had to adopt an entrepreneurial approach to integrating the past, present and future so they could transition to the company of tomorrow. To do so, Drucker says, top management must ask itself two key strategic questions: “What will the business be?” and “What should the business be?”

5. Company Culture

Drucker urged business leaders to hire a mix of different types of employees with different skills, values and levels of commitment as companies change over time. Surprisingly, he also recommends that companies allow no more than a 20% to 30% difference between top management’s salaries and regular employees’ salaries.

He advocated strategic planning as the best way to manage change and said entrepreneurship was a way to systematically manage change. Entrepreneurs must accept uncertainty and risk, but the greater risk is doing nothing because that causes “stasis” and “stagnation.”

6. Customer-Centricity

Peter Drucker’s emphasis on consumer sovereignty broke with the popular wisdom that characterizes a company based on what it produces. Instead, Drucker called for looking at the company from the customer’s perspective. He emphasized the consumer’s need to get value.

His view: Customers don’t just buy a product. Customers buy satisfaction based on a “utility function” of the product, i.e., how they use it and how they benefit from it. You can skip any modern management book that asks “Why?” if you’ve read the original.

7. Manage Your Manager

Today, knowledge workers dominate many spheres of business and work within every organization. These expert specialists are independent-minded individuals who generally are responsible for their own productivity. Those who manage knowledge workers are, in effect, knowledge workers themselves and thus are responsible for assessing their own capabilities – their strengths, their work style, their values and their contributions.

Having said that, effective managers also know that “managing the boss” is a critical component of success. Here is how to do it right:

- Put together a “boss list” that records, by name or function, those to whom you report. It also should show those who have input into your work, who evaluate you or your team, and who you rely on to get your work done.

- Ask each person on your boss list, annually, what you do that “helps and hampers” their work and request that they do the same for you. Reflect on their responses and respond promptly with ways to improve.

- “Enable your bosses to perform” by understanding how they manage. For example, consider whether your manager prefers scheduled or ad hoc reports, whether you should present them verbally or in writing, and what time of day works best.

- “Play to the bosses’ strengths” and downplay their weaknesses to establish trust.

- Keep your manager apprised of what you and your team are doing, not just for approval but to build his or her confidence in you.

- Make sure your boss isn’t caught by surprise. Keep him or her informed.

- “Never underrate a boss” – it may cost you your job.