Education: Now Also a Company’s Business

Education no longer stops at graduation. Learning in the 21st-century world of work is a fluid process, a way of adapting to technological advances and changing workplace conditions.

Even fresh-backed college graduates often don’t have the skills that employers need. For one, technological change often outpaces college curricula. For another, soft skills that are becoming ever more important in the future workplace are not nurtured as part of a college education.

When it comes to workforce skills, organizations face two challenges. They must find ways to bridge the mismatch between the skills universities teach and the skills employers need. And they must take steps to help their workforce keep up the skills needed to compete in a fast-changing business environment.

This has left organizations with no other choice but to assume a much more proactive role in shaping the skills of their workforce. Organizations today recognize that investments in talent must form a core part of business strategy.

These talent investments can take a variety of different forms. It starts with helping high school and university graduates to master the transition into the world of work. It continues with ensuring that their employees keep up the skills they need to perform their jobs in the face of rapid technological change; or, with lines of work disappearing due to automatization, companies may need to help employees reskill so they can move into expected growth areas.

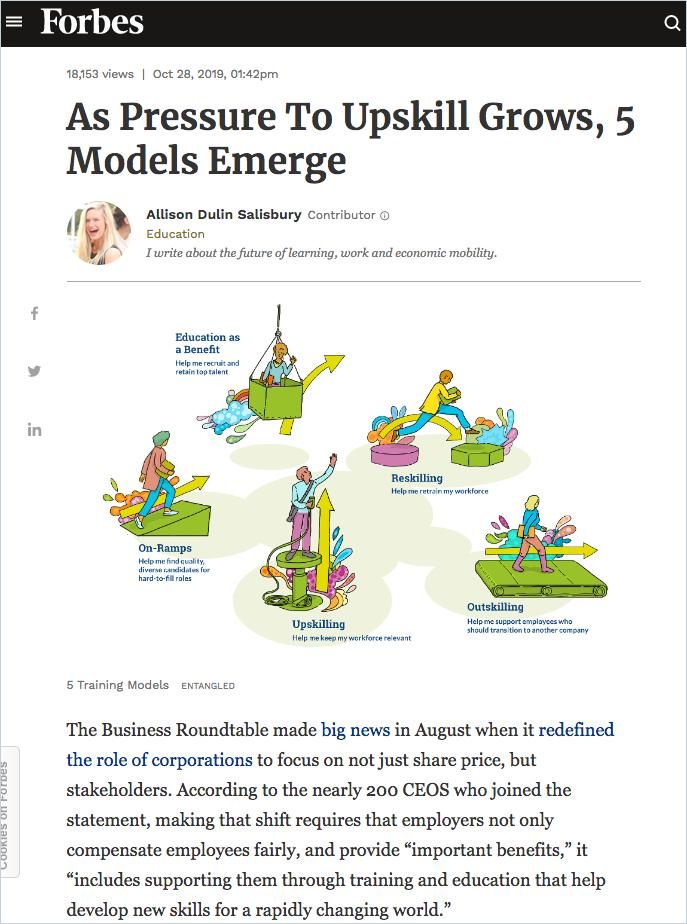

Allison Dulin Salisbury outlines the different categories of corporate training initiatives:

HR technology specialist Neelie Verlinden lists seven formal and informal methods to keep a workforce up-to-date:

New Grads

Many companies have designed months-long onboarding programs to give new college graduates the practical know-how they need to succeed at their first jobs. German business-software company SAP, for example, set up an eight-month program in Silicon Valley to teach new grads how to sell the firm’s software and services. US bank Capital One, meanwhile, runs a developer academy to get new graduates up to speed on business processes and company software.

However, some of the skills employers say are missing in young graduates are more basic. A case in point are analytical thinking and problem-solving skills – skills required to thrive in a fast-changing work environment. A standardized test, called the College Learning Assessment Plus (CLA+) conducted at around 200 US colleges, found little improvement in critical thinking skills even at the country’s most prestigious institutions.

In Bridging the Soft Skills Gap, management consultant Bruce Tulgan offers advice on how to teach critical thinking to gen Z employees: Emphasize proactive learning. Explain that acting “like you don’t know anything” is a good way to acquire new knowledge. Help gen Zers understand the value of “suspending judgment” and “questioning assumptions.” Have them brainstorm these concepts, including thinking of examples of how people use these approaches effectively.

Employers will want their young workforce to know how to apply best practices to novel situations. If new hires haven’t honed this ability in school, it’s up to the employer to teach the missing basics.

Apprenticeship Programs

Apprenticeships are among the oldest forms of training at the interface of work and learning. In countries like Germany and Switzerland, these partnerships between employers and educational institutions continue to form an important part of the work culture. In the United States, efforts are underway by the US Department of Labor to promote this form of workforce training as an alternative to a four-year college degree. From hospitals and banks to industry leaders like Amazon, an increasing number of US employers recognize how apprenticeship programs are a valuable investment in securing a robust workforce.

Educating yourself as you work is the peak of informal learning, explains L&D expert Robin Hoyle:

Partnerships with Educational Institutions

Employers have started to form mutually beneficial partnerships with postsecondary educational institutions. The US medical technology company Cook Medical, for example, pays for some of its employees to enroll in credential and degree programs at higher educational institutions that it partners with to help employees catch up with the specific skills they need for their jobs. Educators benefit from employer input in the design of school curricula as it allows them to better prepare their students for landing a job after graduation. Meanwhile, tuition-paying employers can ensure that employees enrolled in the programs acquire the skills they need. Students enrolled in these programs also win, because they know that what they are learning will be directly applicable to their jobs – which is not always guaranteed for people who go back to school to improve their employment prospects.

Colleges and other educational institutions can partner with the private sector to share information about up-and-coming skill needs, which can shape curriculum development. A report by Adecco Group and the Boston Consulting Group concludes:

CUNY professor Cathy N. Davidson presents examples of new educational models that US community colleges and elite universities are exploring. She provides a list of simple techniques on how to shift classrooms toward a more active learning model:

Lifelong Learning

Over the past decade or so, an increasing number of universities added “continuous learning” departments to their offering to meet growing demand for learning among working professionals. In South Bend, Indiana, employers joined forces with educational institutions, public and private training entities, and community groups to create an innovative system of lifelong learning. On an online portal, employers continuously update their list of skills they are looking for. The portal then shows where and how these skills can be acquired – be it through online or in-person courses, mentoring sessions or job-shadowing experiences. People who participated in learning opportunities can earn badges they can add to their resumes.

Companies benefit from the system as it makes it easier for them to find employees with the skills they need. Yet the example demonstrates companies’ growing willingness to play a role in promoting lifelong learning among the broader public – for their own benefit, yes, but also as a way of giving back to their communities by enhancing employability prospects.

This special report from The Economist surveys trends, innovations and opportunities in lifelong learning:

Rethinking Credentials

Recruiters know: A formal university degree has less and less to say about whether job applicants have the skills required to thrive at their jobs. If specific technical knowledge is needed, candidates may have acquired them in other ways, such as through online courses outside of traditional education programs. Companies would do themselves a disfavor if they limited their search to graduates from specific university programs. Hence, initiatives are underway to quantify credentials in new ways. For example, the Credential Registry is a continuously updated online database on all types of credentials and their associated competencies and learning outcomes. The job application platform Skillist, meanwhile, allows employers and job seekers list individual skills rather than formal degrees. Instead of listing university degrees, candidates list individual skills and describe how they developed and acquired them. According to the site’s co-founders, “We encourage users to draw from all aspects of their life, adding personal achievements and volunteering to more traditional professional activities like education and work history.”

Doubling Down on Soft Skills

These efforts point to a rethinking of the relative importance employers put on “higher education” as a way to gauge the intellectual competence and job potential of their candidates. Research indicates that a candidate’s willingness to grow and the way his or her personality fits into the company culture are often more important indicators for career potential than a set of fixed technical skills.

Companies benefit from people who approach work tasks as learning opportunities. Carol Dweck explains:

Critical soft skills, such as high levels of emotional intelligence, are often mentioned as among the top future job skills. As artificial intelligence and automation take over many routine tasks, employees can most distinguish themselves by excelling at tasks machines cannot replace.

Organizations seek new hires who have good listening skills, who accept criticism well, whose personalities exhibit overall situational flexibility and who are self-directed. As Daniel Goleman explains:

Qualities such as resilience, empathy and social skills are not skills that universities take much into account when selecting students. Moreover, university curricula are not designed to develop these qualities in students either. The importance of soft skills for career success and universities’ failure to nurture them may further devalue college degrees – and widen the skills gap between what universities teach and what employers want even more.

The Future Role of Universities

Considering the high costs of college tuition, the question arises: Why enroll in a traditional four-year college degree program in the first place? Over the past decades and even centuries, the purpose of a college education has varied: to signal prestige; to partake in the “college experience”; to increase job and salary prospects; or to acquire specific practical skills. But this list leaves out one of the main purposes for why students have pursued traditional liberal arts degrees for centuries: to become a well-rounded person – with skills that can be transferred to many lines of work.

George Anders posits that people who infuse “a humanist’s grace” into “technical disciplines” meet the employment needs of contemporary society:

Any subject of study – be it medieval literature or Latin or anthropology – can serve as a vehicle to practice skills that will only gain in importance in an automated world of work: critical thinking and writing skills, as well as the ability to grapple with ambiguity, contextualize needs, and evaluate facts and evidence.

Broadening your knowledge horizon through a university degree (as opposed to specializing in a specific niche) will also help you become a more creative thinker. It will help you make new connections between different areas of knowledge, a skill very sought-after in an innovation-driven economy.

As theoretical physicist Tom McLeish explains, science and the arts draw from each other: Science involves reimagining nature in a way that is similar to the ways novelists create fictional worlds:

The German concept of Bildung, particularly as the thinkers of the 18th-century Enlightenment understood it, represents an expansive vision of education. Bildung entailed not only schooling but also feeding curiosity and developing character, values and knowledge. In The Neo-Generalist, business adviser Kenneth Mikkelsen and writer Richard Martin make a strong case for why people who cultivate a wide range of intellectual interests and embrace a lifelong learning mind-set are so valuable to 21st-century organizations.

A liberal education builds a foundation for thinking and learning – skills that will serve people for the rest of their life and career. Fareed Zakaria convincingly argues that today’s work world needs people who can compose, write, design and create as well as people who can calculate, analyze and code:

Some may argue that universities should take up a bigger role in workforce upskilling and reskilling. That would mean expanding lifelong learning programs and offering stand-alone courses focusing on the acquisition of specific skills. But it may be equally true that the Fourth Industrial Revolution will bring universities back to their roots. If the goal of a university is to develop first-rate humans as opposed to second-rate machines, a well-rounded liberal arts education may be a better way to prepare for an unpredictable work environment than a focus on practical skills that most likely come with an expiration date.