Why Big Plans Fail

After the Berlin Wall fell, then-chancellor Helmut Kohl predicted: “In three or four years from now we will enjoy flourishing landscapes in Eastern Germany.” Around the same time, my roommates from university and I were renovating our little student flat – for six seemingly endless months. So I did the math: five new states versus a three-bedroom apartment. It became apparent: Our chancellor had not the slightest idea what he had put himself up against.

When it comes to executing ambitious projects, we tend to overestimate ourselves. We sit down to work out a concept, do the planning, estimate the required time, cost and material – to later realize that all our meticulous calculations aren’t sustainable when put into action. The most prominent example of this dilemma is the communists who ordered their most competent experts to develop a national economy’s perfect concept. To ensure energy supply in the Soviet Union, they built gigantic machines for extracting coal and iron ore. Then they burned the coal to melt the iron, with which they made massive machines for extracting coal and ore – a perpetuum mobile of inefficiency.

And even though each state-planned economy has always led straight to ruin and disaster, politicians still seem obsessed with the idea of controlling a nation’s fortune with all kinds of rules, regulations and laws. This, of course, isn’t always disadvantageous: If ever again Germany comes up with the magnificent idea of starting a world war, all we’ll have to do is trust the Berlin Senate with the strategic planning.

So why is it that so many excellent plans fail? Even when the most brilliant minds have worked them out? Let’s take a brief excursion into physics:

Only 120 years ago, natural scientists were convinced that by applying Newton’s Laws of Motion, one could calculate and describe the course of any given system. All one needed to know were possible influential factors and initial conditions. As if our entire world was a complicated but computable apparatus. And indeed, over time, scientists became better and better in precisely predetermining various phenomena.

Note

Our columnist Vince Ebert speaks at congresses, conferences and company celebrations in German and English on the topics of success, innovation and digitization. Here you can hire Vince Ebert as a keynote speaker for your event.

The Theory of Relativity, for example, allows predictions of astonishing accuracy. As a result, Einstein proved that a delayed train is perceived entirely differently by a passenger on the train than by a pedestrian who looks at the train from the outside. Fascinating!

Even so, nobody was able to predict the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. The stock market crash in 2008. Or the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in 2020.

It Is Complex, Stupid! (Not Complicated)

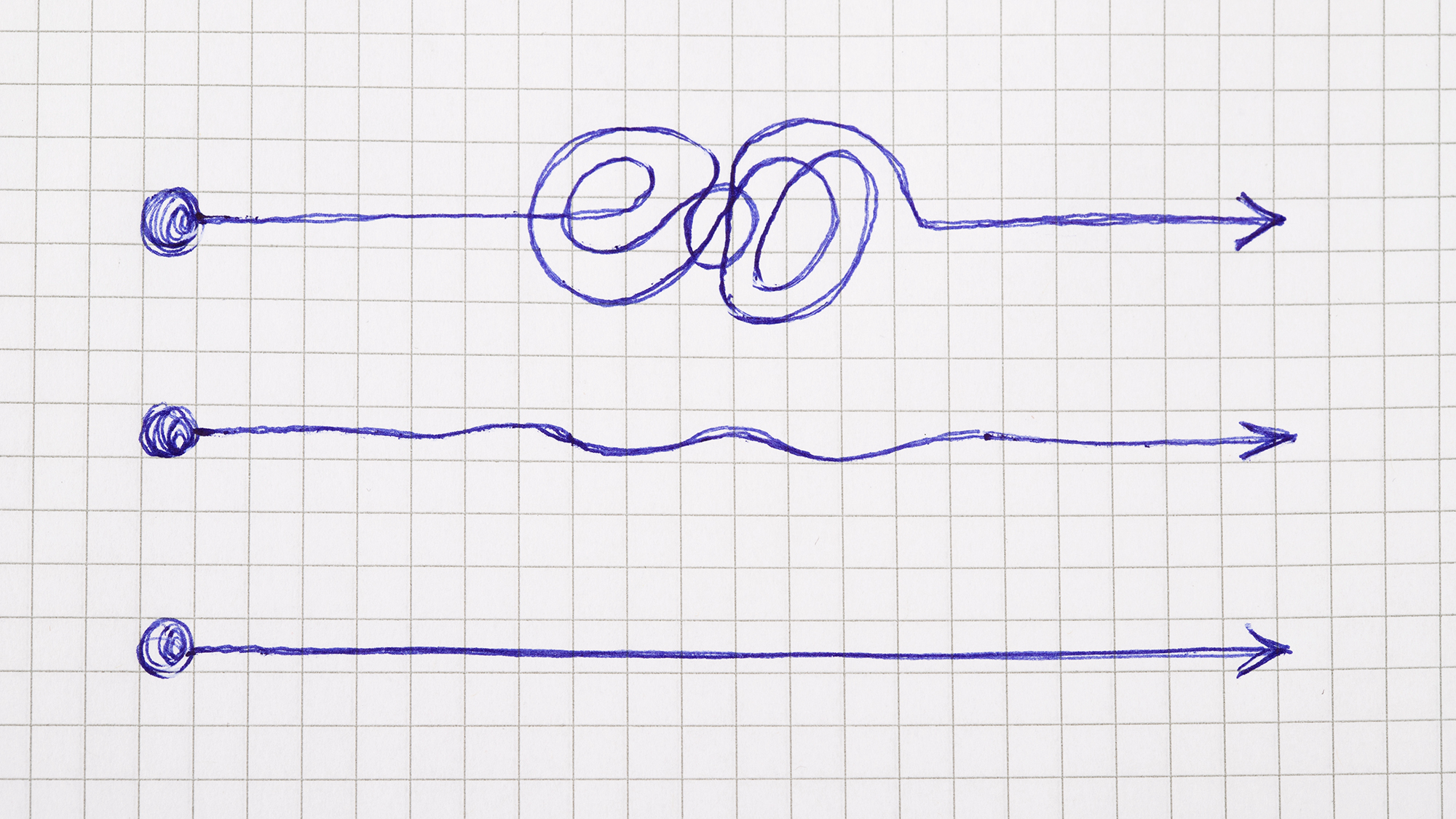

By now, we have learned from physics that our world is not a calculable machine but a system whose course evades description, even with the most efficient of supercomputers. “Complexity” is the magic word here. One of the characteristics of a complex system is that tiny, coincidental fluctuations of the initial condition can have an immense impact on the final result. Physicists phrase it like this: A system does not behave linearly.

Twice as much money does not result in twice as much achievement – often the exact opposite is the case. Two days in Lubbock, TX, are not twice as nice as one day there. Trust me, I tried.

When fantastically conceived plans fail, it is often not because the people involved are not intelligent or competent enough. Projects fail because the people in charge mistake a complex system for a complicated one. An airplane, for example, is a rather complicated thing. But with the necessary know-how, it can be operated quite accurately. Building an airport, on the other hand, is a complex affair. And as we were able to witness in Berlin, complex systems tend to behave unpredictably.

The same is true in economics. Among the typical reasons for entrepreneurial plans to royally bomb is the incapability to adjust to change. Kodak did not believe in digital photography. Today nobody still believes in Kodak. Enron liked to refer to themselves as “The World’s Greatest Company” – right up to their great crash in 2001. But at least on paper, their business plans were immaculate!

None of that means that we shouldn’t make plans. On the contrary: Plans are vital. They serve as guidelines. If the German Railway Company didn’t issue timetables, we would have no idea how late their trains are running. But plans are useless if they are not aligned continuously with reality. Or, as the Prussian General Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke put it 150 years ago: “No plan survives initial contact with the enemy.”

Too Vain to Fail

But instead of staying flexible and adjusting to changes, we cling to our meticulously elaborated original plans. And when our project goes down the drain, it wasn’t us! No way! It was the stupid reality that refused to submit to our brilliant theory.

Even the most intelligent planners fall victim to this misconception. In England, city administrations would stubbornly hold on to gas lanterns to illuminate streets well into the 1920s. However, electric light had proven to be far better in serving that purpose in most big European cities. Why did the Brits do that? Because the British government had invested so much money in gas lighting that they just couldn’t let it go. This behavioral mechanism can be found in almost every major project of every era of every culture.

But from time to time in human history, something extraordinary surfaces: insight and reconsideration. Piece by piece, robust and more flexible ideas of belittled outsiders rule out established experts’ rigid and flawed concepts. We are, after all, able to identify and correct errors.

Or maybe it is more like German physicist Max Planck once claimed: “Better ideas don’t assert themselves by convincing, but by outliving their opponents.”

For further reading on the topic, Vince recommends the following from our knowledge library:

Photo: Frank Eidel