Rethinking Nuclear Energy

In December 2022, the US Energy Secretary announced that, for the first time, scientists could achieve nuclear fusion, where atoms combine to produce more energy than they use, releasing heat in the process. The sun works in this fashion as well. Although this milestone is progress, practical applications for fusion, such as its use in electricity generation, remain theoretical.

Today’s nuclear power plants use fission, which splits atoms in a heat-producing chain reaction that vaporizes water and turns turbines to generate electricity. Fission, however, unlike fusion, creates a toxic radioactive byproduct that must be securely stored away from humans, animals and water.

Nuclear power is a low-carbon energy solution.

However, exorbitant prices to build and secure plants coupled with safety concerns about nuclear waste and the potential for disaster caused most of the world to reject it as a green source of energy in favor of more distributed and renewable technologies such as wind and solar. Until now. Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine caused a worldwide energy crunch which has forced world leaders to take a new look at nuclear power. Consider these points:

1. Nuclear Power Plants Do Not Emit Carbon

That’s not to say the process of building and managing plants as well as mining and processing the radioactive materials that fuel them is carbon-free. Degradation from nuclear’s water needs may be more environmentally problematic. Ultimately, uranium, the basis for nuclear fuel, is a finite resource. But even noted environmentalist Greta Thunberg is on record supporting nuclear energy in the cases where it is already in place, rather than building more fossil fuel-based plants. For many countries, including China, nuclear is part of their strategy to meet carbon emission reduction goals.

Coal-powered plants currently make up 65% of China’s available electricity. The country’s plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 include increasing investments in nuclear energy. Renewables will provide some margin for the carbon emissions the country does not believe they’ll be able to eradicate before mid-century, according to Smriti Mallapaty in “How China Could Be Carbon Neutral by Mid-Century.” China will invest more in energy storage solutions, reforesting and carbon capture technology to ensure that, by 2030, 60% of its energy is derived from non-fossil fuel sources.

We need to know where our energy is currently being supplied and used so that we can substitute cleaner sources of energy, and cleaner end uses of energy, to get a carbon-free future.

Saul Griffith

Scientist, inventor and author of Electrify Saul Griffith is an evangelist for renewable energy. He advocates electrifying everything, starting with cars and homes. To replace every machine people use with one that runs on electricity rather than gas, coal or oil will require three times more electricity and an updated grid. Less energy, however, will be required to supply that capacity.

Rather than reducing demands, the mantra of environmentalists, the ultimate result of Griffith’s vision removes carbon from the air creating a cleaner, greener world while at the same time providing abundant energy from renewable sources. This is the best way, he argues, to meet mid-century emissions reduction goals, but, especially for some countries, nuclear is an indispensable part of the mix.

America can reduce its energy use by more than half by introducing no efficiency measures other than electrification.

Saul Griffith

2. Nuclear Energy Is Reliable

Finding reliable low-carbon solutions to power generation inevitably leads to nuclear solutions. According to economic historian Daniel Yergin, the world’s energy crisis started well before the invasion of Ukraine. He cites heightened volatility in energy markets and the attendant changes to those markets as the world transitions to non-carbon-emitting technologies.

The problem is the world needs a solution to the thornier problems that have kept renewable energy from massively scaling up. In the US, money for renewable infrastructure set aside in the Internet Reduction Act will help, with large investments across the spectrum of energy solutions and decarbonization. A clean energy transition is vital to confronting the effects of climate change. And, from Bill Gates‘ perspective, increasing nuclear power generation is the only clear path forward to reducing atmospheric carbon emissions 90% by mid-century. However, nuclear has its own issues with scalability and timelines.

As Gates discusses during a post-Fukushima talk on energy innovation, fossil fuel-powered plants are the sites of energy “factories,” whereas renewable energy from solar and wind comes from energy “farms.” The farms take up enormous land areas compared to the factories, and the output is intermittent, unlike the controllable output of energy factories. Non-carbon-emitting nuclear generation, especially in high-demand urban areas with less available land for energy uses, is far preferable to building more fossil-fueled stations to provide anchor baseloads for a reliable grid at scale. Gates puts his money where his considerable intellect has taken him: He is invested in TerraPower, a company building next-generation, smaller nuclear power plants in the US, with the aim of replacing coal-fired plants. Unfortunately, the war in Ukraine has put his projects on hold: Russia provides the fuel for his reactor.

Read some of the titles Gates recommends to stay informed on energy issues:

While in theory, nuclear provides a reliable, controllable source of energy at utility scale, consider that France, long dependent upon nuclear for nearly 70% of its energy needs, and usually an energy exporter, is having unprecedented problems keeping its reactors online due to safety issues and the insolvency of the agency that administrates them. Finland’s OL3 reactor has similarly faced operational delays. The plant was originally scheduled to be up and running in 2009.

3. Safer Designs Reduce Traditional Worries that Accompany Building Nuclear Energy Plants

Nuclear plant disasters, especially Three Mile Island in the US, Chernobyl in the then Soviet Union, and Fukushima in Japan, alerted the world to the terrible potential downside of nuclear energy, which contributed to lengthy stagnation in the industry. More than ten years later, the Japanese government is still grappling with what to do with over one million tons of radioactive wastewater still stored at the site. The radioactive fallout, both figurative and literal, is not just Japan’s to deal with, as its Pacific neighbors continue to remind the country. Russian shelling around the Ukrainian Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant gave the world fresh worries about unforeseen dimensions of nuclear warfare.

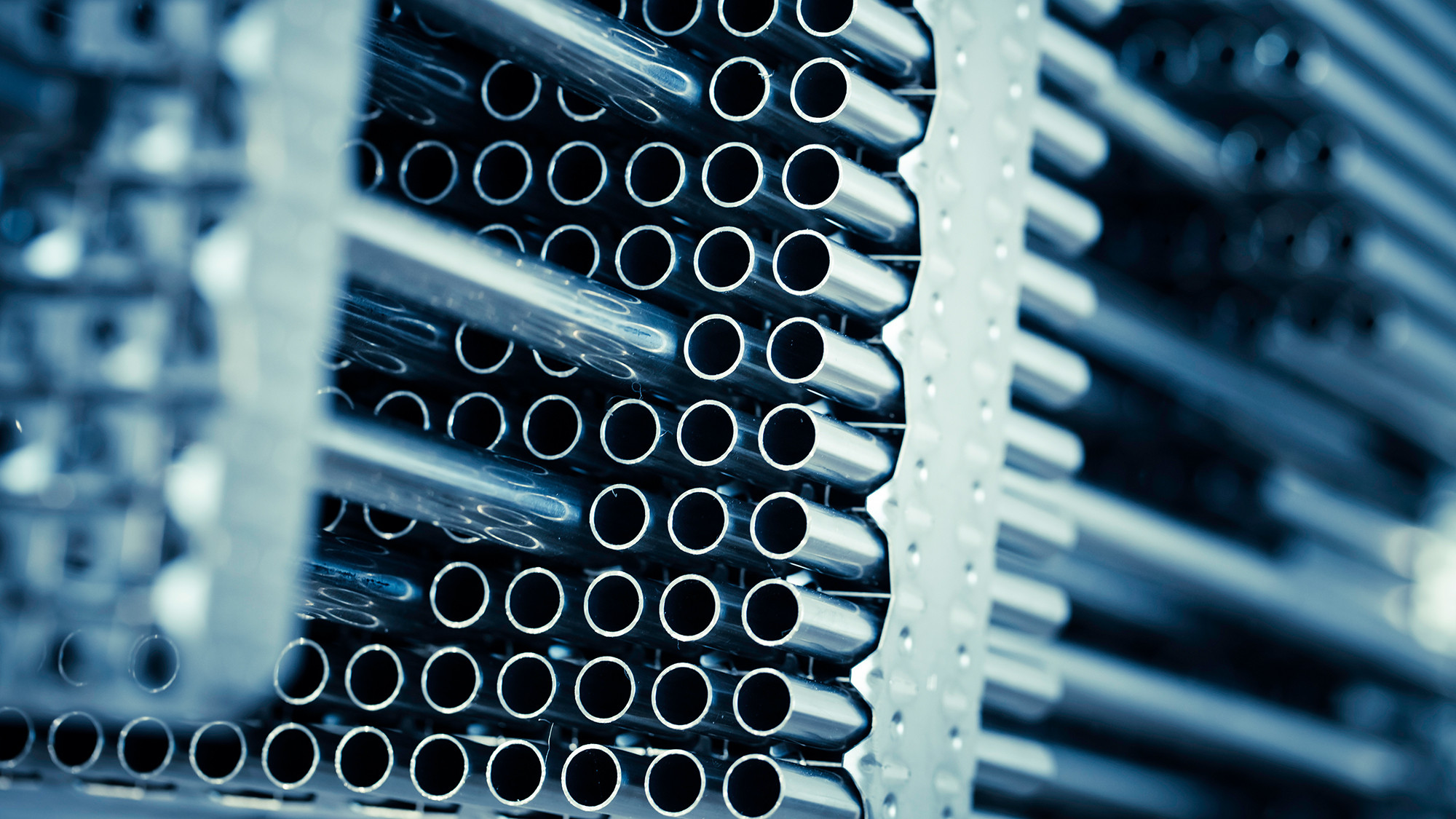

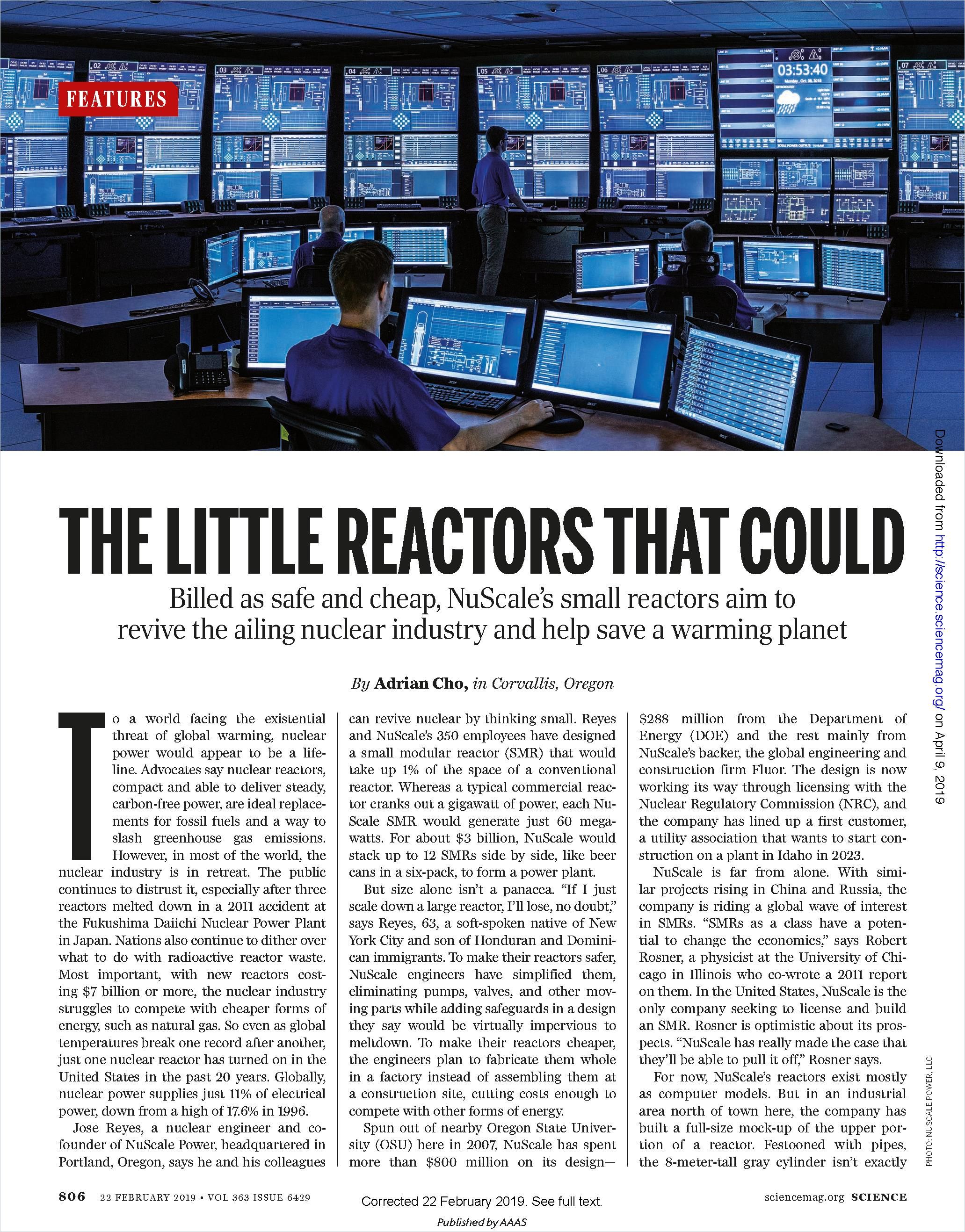

Journalists Heidi Hutner and Erica Cirino argue in “Nuclear Power is Not the Answer in a Time of Climate Change” that in a warming world, nuclear may be an even less safe option, considering the heightened threats of wildfires and rising seas. They also argue that renewables-fueled stations produce more energy per investment dollar and are inherently less risky. But newer, safer reactor designs have revived interest in nuclear energy. Small, modular reactors (SMRs) are more compact than previous generations of reactors. They are considered “generation IV” designs.

Because the reactors are manufactured as contained units and connected together on-site with the total number used depending on the ultimate output desired, they are inherently safer than previous models. They’re also cheaper, argues Science journalist Adrian Cho.

For about $3 billion, NuScale would stack up to 12 SMRs side by side, like beer cans in a six-pack, to form a power plant.

Adrian Cho

CEO Leslie Dewan, co-founder of Transatomic Power, which designs generation IV nuclear reactors, explains how newer reactor designs vastly reduce the radioactive waste they generate. Dewan says Transatomic Power reactors can process the world’s existing nuclear waste – 270,000 metric tons of it in 2014 – as new reactor fuel capable of generating 72 years worth of electricity to meet the world’s growing demands.

We should start viewing nuclear waste as an important resource to be tapped, as a valuable material, rather than as a liability to be disposed of.

Leslie Dewan

Experts say nuclear energy organizations would do well to better engage the public on their concerns. Nuclear disasters are low-frequency events, but they come with high costs, and acknowledging that and mitigating those costs will go a long way to shoring up public buy-in.

These Journal articles offer additional insights about climate change, energy and looking toward the future: