“In Times of Confusion, It’s Crucial That the Message Gets Through.”

Esther Duflo and Abhijit V. Banerjee, let’s get straight to the topic: Will COVID-19 be a setback in the, so far, successful fight against poverty?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: Right now, it’s a disaster. First, I think our economies are paralyzed. And second, I think, economic thinking is paralyzed in some ways, too. Both are feeding on each other. That’s why the policymakers really do not know which way to turn. They are extremely busy fighting the infection. And the combination of those things means that they’re a bit like a deer in the headlights. We have poor policy combined with a big shock. And that’s not surprising. It’s an unfamiliar new shock. Nobody, even in Germany, where they are doing very well, had a measure of it, and it’s still an extremely unusual circumstance to be in. In many poor countries, on the other hand, it’s still at the level of just getting through the day. But the economies are bouncing back. How far? How fast? It’s anybody’s guess. There are a whole range of possibilities, including the one that, relatively quickly, the economies go back to the pathway they were on – with a big loss. A big, but maybe not a permanent, loss. That still remains a reasonable possibility, and it depends on the policymakers and on how well, how adroitly they handle the shock.

Do you think that especially the poor countries, which can’t afford a second wave or a second lockdown, can tackle the economic consequences of the spread of the pandemic successfully?

Esther Duflo: They are certainly in a weaker position than the rich countries – but not necessarily because they were hit harder by the virus. In fact, many countries in Africa so far have been hit much less badly by the novel coronavirus, at least to the extent we know. But they are not in a position to borrow to help smooth out the economic shock that goes with the measures they have to take such as lockdowns, but also the fallout from the fact that all other countries in the world face an economic crisis. So, if we take a very poor economy in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, it was simply not in a position to do what Europe did or what the United States did, which is to go on a spending spree.

If poorer countries try to borrow, then first, nobody is going to give them the money and, second, they couldn’t endure their credit risk, which would put them in an even weaker position in the future.

Esther Duflo

So, very early into the crisis, we made that point and we called for a Marshall Plan for the poor countries to help them deal with it. But the rich countries have been completely absent. There has been very little international solidarity. The rich countries were completely obsessed by their own issues. Perhaps it’s understandable. But, as a result, the poor countries have been left trying to deal with this situation on their own. And that fact makes things much worse than they could have been otherwise.

What was the Marshall Plan about in concrete terms?

Esther Duflo: Well, there were two aspects to it. One, of course, is the health aspect, which turned out to be maybe less critical because, in many of the poorer countries, COVID did not have the impact we feared it would have – I’m not including middle-income countries here, like Brazil and India that were hit the strongest. But if you take the poorest countries, they needed help. Some of them have only two or three ventilators in the entire country. And they all have very underfunded health care systems that need help with personal protective equipment, or gear for hospitals. But, and that’s the second aspect: They also needed economic help to be able to immediately support their citizens in the midst of the economic consequences. What we advocated for very early on is to immediately go and provide unconditional relief. In a lot of African countries this would have been possible using cellphone electronic money, for example. But that requires cash. And very few countries were able to do this in a sufficient way because they just didn’t have it.

Rich countries had their own problems: They had to fight the coronavirus themselves, and they simply had no money capacity in time…

Esther Duflo: The problem is not capacity. The suggested help would have been a drop in the bucket compared to the money they spend on themselves. It’s more the fact that they don’t have visibility on their own problems.

Mr. Banerjee, you are on the council of advisers in India…

Abhijit V. Banerjee: In the state of West Bengal. Health is a federal subject in India.

What is the policy advice that you gave to the state? What is the most efficient way to tackle the pandemic using as little money as possible?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: Well, interestingly, right now is the moment where our advice is most useful. They hit a very specific problem, which is that the annual social-religious festival Durga Puja is coming up.

There are 90 million people in West Bengal, and a lot of them are out in the streets partying – it’s like a carnival for five days. That’s potentially going to cause a disaster in a place where the number of infections is rising all the time and is already very high.

Abhijit V. Banerjee

So, one of the things we’re trying to do is to map out a proposal for how to manage this sentimental and important event to keep it relatively safe – without canceling it. We have given 15-point memos to the government advising that the festival should be organized as far as possible outdoors and in ventilated areas, etc. And they have, in principle, accepted our recommendations. They have been responsive. Very responsive.

Why do you put so much emphasis on the last point?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: In this crisis, it’s key that if you don’t master the details – and that’s sort of what makes it very hard, because there are a lot of details and a lot of them were, I think, not understood at the beginning – you have to take small steps. In the United States, for example, they said masks are optional, or even “Don’t use them”, and when they first became essential, then mandatory in some places, everybody was confused. Even today, many details are not yet understood. Governments simply don’t have the capacity to interpret every new study in publications like The Lancet or in Science to react accordingly. And when it comes to India: They are still lagging behind in many parts, prescribing [the anti-malarial drug] chloroquine or something. It’s a big technocratic challenge to provide the necessary know-how, so you have to give the advice that makes most sense at a single moment.

Usually, before you give economic policy advice – and this is also what you won the Nobel Prize for – you conduct trials. Could you give an example of how you do these studies and of the findings?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: One of the trials we did right after the pandemic started had to do with a video I sent to 25 million people. Because of the Nobel Prize I am well known in West Bengal and I was chosen to record a video to help Bengals following the COVID-19 rules. So, in the first place, there were several million people, randomly selected. We’ve sent them a SMS with the link to my video, and, interestingly, it had effects on all kinds of behavior, which was seen as a success. So, we did another video, and sent it to around another several million people to see what could be improved. In all, eight variants of these video messages were sent, to a total of 25 million people with three million people in the control group, each emphasizing one necessary routine to counter the virus – such as social distancing or hand-washing – or a social problem to tackle that occurred with the virus. In between productions, we’ve been working on how to design and improve the next messages to see what proves to be effective. Currently, we are doing the same in the United States. I certainly think that this kind of work with COVID is even more essential. In times of confusion, it’s crucial that the message gets through.

But sometimes the insights you gather from your trials must be quite ambiguous. Since people want simple answers to complex questions, for example on how to tackle poverty, what do you tell them?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: As we say in our book, Good Economics for Hard Times:

There are no silver bullets when it comes to deal with poverty. There are only silver ballots.

Abhijit V. Banerjee

I think the current coronavirus crisis made it very clear that poverty is a set of many different, separate problems and therefore you need many different, separate answers as well. At the moment, for example, it seems like the world’s poorest are not hit as hard as estimated in the first place, because they live in remote villages and crop their own land. Actually, these families are relatively unaffected, because they were growing their own food and had no access to places where the virus is spreading. The migrants who were making a reasonable living in the cities were hit much harder, because the cities were shut down – and with it their daily income and their perspectives. That is what we mean when we talk about the many silver ballots: You need to identify the real problem before you try to solve it.

Since 2001, the getAbstract International Book Award has been presented annually to books that make a particularly important contribution to current economic, social and business-related topics. In this anniversary year, the prize will be awarded symbolically through a series of interviews and digital events. Find out more here.

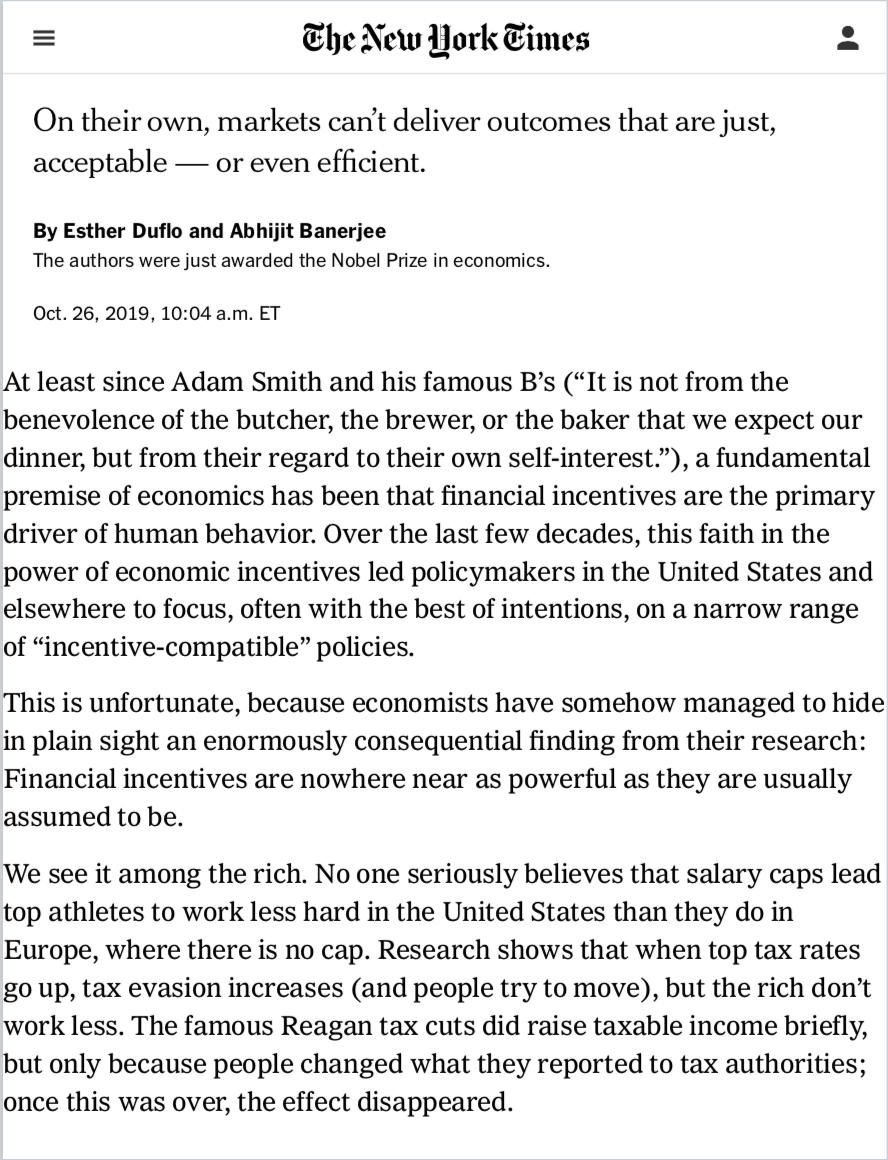

The image of those silver ballots is correct, but, unfortunately, as the American economist Robert Shiller recently pointed out, the ideological narratives in economics prevail because of even better pictures and stories that stick – plausible sounding one-size-fits-all solutions, for example.

Abhijit V. Banerjee: I think one thing we don’t do well in economics is to grant the viewer his or her intelligence. We all must acknowledge complexity. So, we try to give our audience a lexicon for thinking about why some things are complicated and you just can’t reduce it to one formula or the other. I think what economics has done for too long is, in a sense, tried to reduce things to a simple dilemma – for example, that you have to tolerate lots of inequality and poor people suffering to have the right incentives for growth.

That very simple opposition between every regulatory cause and growth has been the core message of economics for so long. And we really want to push back against that, because there is no proof for it.

Abhijit V. Banerjee

We try to fight simple messages. That doesn’t mean that economics is completely inaccessible or mysterious. It’s actually pretty commonsensical! But in many cases you have to unlearn the particular common sense that economics has taught you in the first place. Only then, you actually learn something useful from it.

Are there any completely new ideas in the fight against poverty that have evolved during the past six months as the crisis unfolded? Totally new approaches because this has changed so much?

Esther Duflo: There might have been. I don’t know. I haven’t had any radically new ideas. But it’s not really the way I function. That relates to the silver bullet question: We are never really looking for one new idea that changes everything. We are working with many kinds of partners to evaluate the various ideas to make incremental progress. So, when faced with the coronavirus, the temptation to find something that is going to make the entire problem go away is very big. We can see it in the public and politicians’ obsessions around a vaccine. But even the people who work on a vaccine tell us: Look, there won’t be a perfect vaccine. We’ll have an “okay” vaccine or, in fact, more than one okay vaccine. And at the same time, other things will improve. The treatment has already improved; people are better at protecting themselves. We understand better what’s important and what’s not. You see, the problem’s solution is not going to be one genius discovery. And, I somewhat agree, that’s disappointing, because we would, very much, want to wave a magic wand and then go back to where we were sometime in late 2019. With poverty it’s the same thing. It is not going to be erased by one magic treatment.

And if you look at the past several decades since the early 1990s, there has been tremendous progress in the fight against poverty, in many different variations of poverty.

Esther Duflo

And because now, with COVID, it’s worsening again, we will need to climb out of this, readjusting to the new circumstances one step at a time.

But will economic policy improve through – and after – the crisis?

Abhijit V. Banerjee: In a way, yes. But I think mostly because if this crisis did anything, it made it very clear how fragile our prosperity is. Even in the United States, suddenly everything was just frozen, falling apart. And maybe what that does – and I really hope it’s true – is to make people realize that we live shared lives on a very fragile planet. Once that happens, it creates an economic discourse, and this discourse will generate a different attitude to policy, maybe a more humane attitude to policy. That’s the most optimistic view. And you can see a little bit of a trend towards this in Europe. There seems to be a continental European consensus, with a little hint of views coming together, that in the end the state is important. Of course, its actions must be challenged, but the state has a very critical role to play in modern lives. Its consequent delegitimization in the last 25, 30 or 40 years since Ronald Reagan did neither economics nor our economists much good.

Esther Duflo: Everybody realized that it’s actually quite convenient to have a guardsman because who else is going to enforce a mask mandate and who else is going to borrow at a low interest rate to make sure that we can continue to pay our bills during the lockdown? Having said that, I’d like to add two aspects to the “shared lives on a fragile planet” thought. One is the fragile planet bit, which is, I think, that it has made people aware that sometimes nature is just bigger than us and sometimes the crisis that is foretold by scientists will happen.

Human psyche suffers from projection bias: As long as things are not broken, you cannot imagine that they might be one day. What we have seen in this crisis is that it’s not that epidemiologists were not telling us that there would be a pandemic one day. The problem is that nobody paid attention.

Esther Duflo

Least of all me or him [points to Banerjee]. But this, we saw. And we said: “Oh my God, this is happening!” I think this could really change the way people pay attention to other scientific warnings – for instance to climate warnings.

Economic Incentives Don’t Always Do What We Want Them To

The New York TimesAre there any hints that this is already happening?

Esther Duflo: Yes. We have seen it in France’s municipal elections. The first one was before COVID, the second one was after COVID. And the Green Party just cleaned up like never before. People start to realize the fragility of the planet. And a “shared life” is the idea that, usually, when in a normal state of life, some people suffer economic shocks that are in most cases not their fault, then they need help and the rest of us are very suspicious and don’t want to give them any help. That’s why social protection systems are very unkind to anyone who needs help. Now, this crisis is a shock that hit everyone at the same time – and suddenly, most people needed help, at least to some extent. This might make people realize that sometimes you are hit by a shock and it’s not your fault. And, yes, people who were hit by the shock should be helped. This thought might stay with people, even after the COVID crisis is under control. And it might change the political decisions they go for.

How is living and working in the United States right now?

Esther Duflo: [Laughs.] We are in Paris.

So, are you lucky to be in Paris these days?

Esther Duflo: We had planned to be here this year, long before any of this happened. But yes, we are very pleased to be here. This is a much more serene situation than in the United States today.

You live and write together: What effect does this have on your work? Do you start discussing it at breakfast – and only stop after you go to bed?

Esther Duflo: We talk…

Abhijit V. Banerjee: …all the time.

Esther Duflo: All the time. [Laughs.]

Abhijit V. Banerjee: And we actually don’t have breakfast together, so there is no breakfast table. We both have breakfast on the run while taking our children to school. But there’s a whole day to talk about work…

Esther Duflo: …and once we have talked things through, that gives us a lot of clarity that allows us to put it together, to put it down on paper. And whoever writes it first, it is with much more of a sense of where it should be heading than it was before, because we’ve had the benefit of that ongoing conversation.