Three Women Leaders of Labor

The international labor movement began in the early 1800s and its strength has waxed and waned over the centuries. It ushered in the 40-hour workweek, occupational safety laws and ended child labor, among other reforms. Women have been a part of that movement since its origins at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

The Lowell Mill Girls

Lowell, Massachusetts was a hub for textile manufacturers in the early 1800s. Young, single women flocked to the city for jobs, where they lived in company-owned boarding houses. Perhaps the first women’s union was the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association created by the garment mill workers, which pressed for better working conditions including shorter hours. In 1836, despite an economic boom, mill owners raised the costs of board without raising wages. More than 1,500 women walked out on the job, protesting what amounted to unjustified pay cuts. They won their struggle, with most companies dropping their rate hikes. Many of the young women working in the Lowell mills then would later apply the organizing skills they learned there to building organizations dedicated to winning women’s suffrage.

“Mother” Mary Jones

Born Mary Harris, “Mother” Mary Jones, galvanized by personal tragedy to do something to help low-wage workers in the United States, traveled across the country between the 1890s and 1920s speaking out on behalf of worker rights, primarily miners and railway workers. One politician called her “the most dangerous woman in America.”

Children spent all day stooping over frames that were just two feet from the floor; they would fall asleep and be strapped to stay awake.

Charles Perrow

According to Charles Perrow in Organizing America, factories routinely employed children as young as nine to work 12-hour shifts, often while standing, for a reduced rate. In 1903, after 90,000 mill workers in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania region walked off the job in protest of unfair working conditions, Jones led a “Children’s Crusade” of child workers in a walk from Philadelphia to President Theodore Roosevelt’s New York home to demand child labor law reform. The president refused to meet with her, and major newspapers of the time refused to publish stories about the children, but the march sparked an enduring effort to get children out of factories and into school. A few years later, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York passed meaningful child labor laws.

The New Deal and Labor Reform

In 1911, 146 garment workers, mostly immigrant women, died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, due to lack of safety protocols. Among other hazards, workers couldn’t escape because the factory owner had chained exit doors shut during working hours. A young Francis Perkins was an eyewitness to the tragedy and it affected the trajectory of her life. She would go on to become the first women ever appointed to a US cabinet position as Secretary of Labor, appointed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Although most people credit Roosevelt for New Deal programs, in fact Perkins was the primary architect of many of the era’s projects and policies, including Social Security and public works programs that gave Americans suffering through the Great Depression jobs. She shepherded the Fair Labor Standards Act through Congress, which established a minimum wage, guidance for overtime pay and effectively ended child labor in the United States.

I had to do something about unnecessary hazards to life, unnecessary poverty. It was sort of up to me.

Francis Perkins

“Si, Se Puede“

New Deal era reforms did not apply to farm workers or domestic workers. Hillary Rodham Clinton and Chelsea Clinton write in The Book of Gutsy Women about Dolores Huerta, who co-founded the United Farm Workers Union with Cesar Chavez to advocate for agricultural workers. These workers are often immigrants and work seasonally and itinerantly, according to where there are jobs. They worked in often brutal conditions – long hours, no breaks, no bathrooms and sometimes no water – for large agricultural businesses in the valleys of California. Chavez was the well-known face of the organization, the one most often associated with it, but Huerta was its tireless primary organizer. When everyone told her what she fought for was impossible, she would reply, “Si, se puede,” – “Yes, we can.” This became the Farm Workers Union motto.

The mother of 11 children, Huerta organized a successful nationwide boycott of Coachella Valley grapes which led to growers signing contracts for improved working conditions and basic rights for farm workers. Huerta was among the first organizers to push for worker protections against harmful exposure to pesticides, a fight she continues to this day.

Fighting for the Dignity of Essential Workers

Ai-Jen Poo is the director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, an organization that advocates for better working conditions for homecare workers including nannies, housecleaners and caregivers. 90% of home caregivers are women, mostly women of color. They do the most essential work there is: taking care of the young, the sick and the elderly, helping families take care of their loved ones, yet, as Poo notes in her TED Talk “The Work That Makes All Other Work Possible,” they are an often invisible workforce because they work inside people’s homes rather than offices. They work for low wages and without access to safety net services. Sometimes they are victims of human trafficking and can’t escape their situation. The Alliance works to build a higher profile for domestic workers and for policies that protect their human rights.

In “Advice From Women Who Lead,” 18 women leaders talk about their experience as women leaders. Ai-Jen Poo’s advice to other leaders is: in moments of vulnerability or in the face of criticism, rather than trying to toughen up, instead open your heart and “choose to love more.”

It’s precisely the people who are considered the least ‘likely’ leaders who end up inspiring others the most. Everyday people and everyday acts of courage eventually change everything.

Ai-Jen Poo

Female Labor Supply and Why Women Need to Be Included in Economic Models

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Read Summary

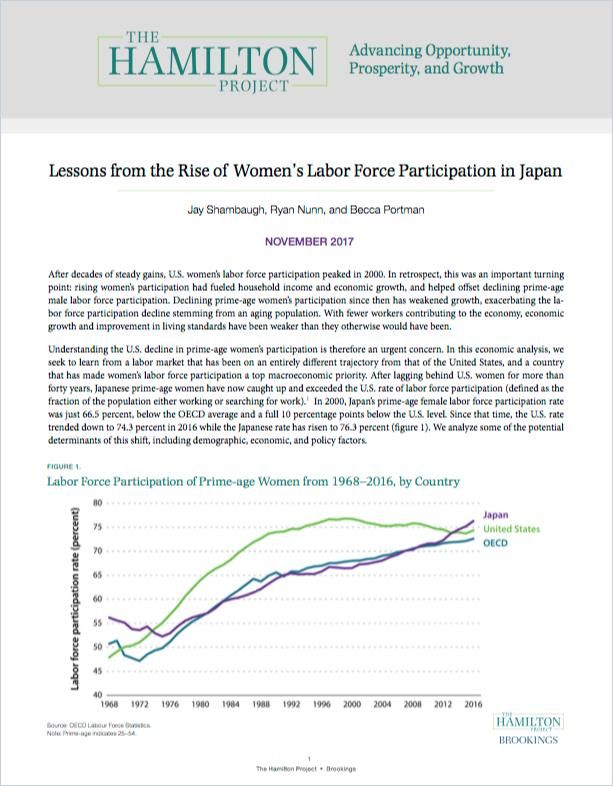

Lessons from the Rise of Women’s Labor Force Participation in Japan

Brookings Institution Read Summary