Smart and Smarter Cities

City planners think about all the different interlocking systems that work together to make a city function. As former Palo Alto Chief Information Officer and Smart Cities for Dummies author Jonathan Reichental said in a getAbstract #gettogether conversation, there is no single, agreed-upon definition for what a smart city is. What’s important to understand is that a majority of the world’s population live in urban areas, and this trend will only grow. “Smart Cities” became a catch-all designation for strategies to manage all that growth.

Smart Cities Are Sustainable

The smart cities movement was originally a sustainability movement. When leaders recognized that burgeoning urbanization would inevitably dump additional megatons of carbon into the atmosphere accelerating climate change, they set about figuring out how to minimize and reduce the carbon footprints of cities. Now, in the era of digital transformation, smart city leaders plan ways to integrate new technologies to improve livability, environmental sustainability – including lowering the carbon footprint of buildings and construction – and responsiveness to residents.

It turns out sustainability is closely related to livability – creating the kind of cities people like to move to and raise families in. Cities with efficient mass transit systems increasingly reliant on renewable energy reduce carbon emissions and traffic congestion, but also make it easier for residents to move about for work or pleasure. Robust transit solutions, not just mass transit, but ride-sharing, pedestrian and bicycling paths, allow for people to live in exurb communities – usually less expensive than center city areas – yet still quickly and flexibly commute to work in downtown areas. Instead of building endless concrete jungle, city density rather than urban sprawl leaves more natural, open spaces untouched, preserving forests and farmland.

Battery electric buses are a more recent invention, but they have a growing market share, with more than 200,000 electric buses sold in China alone in 2015 and 2016.

Hal Harvey, Robbie Orvis and Jeffrey Rissman

Maya Ben Dror and Michelle Avary, lead and head, respectively, of the World Economic Forum’s Autonomous and Urban Mobility portfolio propose a “Shared, Electric and Automated Mobility (SEAM) Governance Framework” for cities as they begin integrating autonomous transit systems.

Shared, Electric and Automated Mobility (SEAM) Governance Framework

World Economic ForumThe ultimate vision is for an inclusive and sustainable mobility system, which improves urban quality of life for all.

Maya Ben Dror and Michelle Avary

Cities with green infrastructure like parks and planted walkways reduce carbon, lower temperatures and give residents a replenishing, easily accessible connection to nature. Walking and biking paths give people room for exercise. Open green spaces help clear air pollution. Green infrastructure also encompasses natural, more effective water treatment solutions for managing polluting stormwater runoff while efficiently conserving water for city plants. “Eco-cities” like Masdar City, developed for a population of 50,000 in Abu Dhabi, aspire to be carbon-neutral.

The Digital Transformation of Cities

Digital infrastructure is as important in the 21st century as roads and train tracks were in past eras because this is the way businesses now deliver their services, and the same is true for cities, as Reichental points out. Cities are adapting to global digital transformation in different ways. In the simplest sense, they’re making their services – help and information, forms and applications – available online.

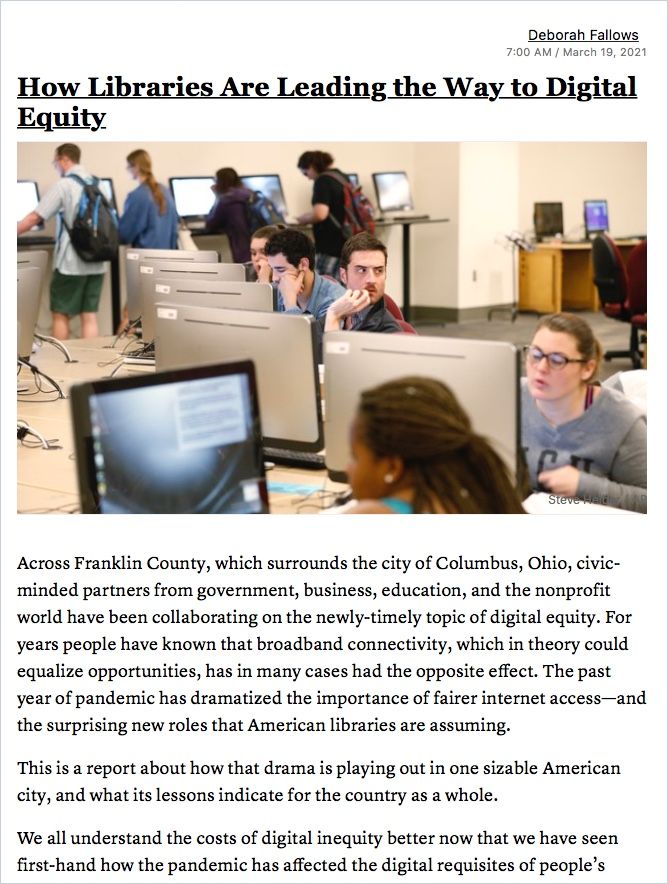

Journalist Deborah Fallows, co-author of Our Towns: A 100,000 Journey in the Heart of America with her husband James Fallows, reports in “How Libraries Are Leading the Way to Digital Equity” the great need for access to computers and broadband internet Columbus Metropolitan Library staff in Ohio witness every day. To them it’s clear the internet is a “fourth utility,” necessary for modern life.

Libraries often offer more than just books, movies and music. They are community hubs for neighborhood groups, toddler story hours, a place where students can get after-school homework help, and residents who may not have computers at home can access the internet to find a job or research reports. A Washington, DC library lends tools and has a 3D printing makerspace for patrons. Library systems offer just one way of extending digital infrastructure with all the access and opportunity it brings into poorer neighborhoods. The public servants that provide these services are examples of the human capital infrastructure good cities rely upon.

Broadband connectivity, which in theory could equalize opportunities, has in many cases had the opposite effect.

Deborah Fallows

“Underdog Cities”

James and Deborah Fallows traveled 100,000 miles across the United States researching Our Towns, visiting 31 third-tier cities, the kinds of places James Fallows calls “underdog” cities. These cities are building on their existing attractive features to lure new businesses to their location and to develop economically. For instance, Eastport, Maine anticipates its deep-water port will be an attractive trade destination to Korea, Japan and China as Arctic ice makes shipping in northern waters feasible. Residents use the tidal currents in the Bay of Fundy to generate regional hydrokinetic electricity.

As companies make permanent their migration to a more digitally connected workforce, and the world eases back into a postpandemic new normal, hybrid work models utilizing a mix of both physical office space and remote teams cause businesses to rethink their investment in expensive downtown headquarters. The Fallowses talk about the “good bones” underlying many smaller US cities, cities that didn’t level their downtown commercial districts even when they fell into disuse.

In Fresno, tech start-up Bitwise Industries has helped that city bootstrap an economic and cultural revival. Fresno is an “underdog” city set in the middle of California’s Central Valley farms, historically poor, but turning it all around by offering a cheaper place to live and a tech hub that focuses on agriculture applications. As Microsoft’s Chief Technology Officer Kevin Scott wrote in Reprogramming the American Dream, in the era of fast-paced technological innovation, regional specialties make a difference as companies build out industry-specific AI-driven solutions. This brings the higher wages that come with a technical education to the usually forgotten areas of the country, so more people can share in the high-tech economy.

We can’t separate who we are from where we’re from. You can’t hire people for livestock that haven’t grown up around it. We have to develop our own developers.

Kevin Scott

Among the cities the Fallowses single out are Greenville, North Carolina, Fresno, California and Burlington, Vermont for their small-town feel and natural beauty. Cities like Allentown, Pennsylvania have old industrial manufacturing bones attractive to modern tech businesses manufacturing a new generation of components. Cities like Toledo, Ohio, a “Rust Belt” manufacturing hub that time forgot, are enjoying a revival. Businesses are reassessing Toledo’s location on the shores of freshwater Lake Erie, updating its image to a “Water Belt” city. In the face of climate change, and especially for manufacturers, access to water will become a greater consideration.

The imbalances in American opportunity – by race, by gender, by neighborhood and region, by class and economics – are of fundamental importance in the politics of the past generation, and in the prospects for renewal in the generation ahead.

James Fallows

Business Infrastructure

Paul Sawers writes in his article “After Embracing Remote Work in 2020 Companies Face Conflicts Making It Permanent” that larger companies will likely pursue a “spoke and hub” strategy where they keep their main headquarters, but invest in smaller physical spaces in various other locations to support a hybrid workforce. As companies pursue these plans, third-tier cities have a chance to attract new business. Now is an opportune time for businesses to leave expensive, highly competitive coastal areas for smaller, more start-up-friendly locations, writes Mark Sullivan in “All the Things Covid-19 Will Change Forever According to 30 Top Experts.” As soaring property values in top-tier cities price out families, those small and mid-sized cities also become more attractive to even well-paid workers. Generally, less polluted areas with green infrastructure and recreational spaces, robust amenities including good public schools and access to higher education or technical training make for nicer places for families to live. “Good bones” is an added draw for businesses trying to attract talent.

Cities implement a variety of public-private partnerships to jump-start revitalization by focusing on their downtown areas. Some cities pair anchor companies with nearby universities or research centers in “innovation districts” to attract other businesses, write Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley in The Metropolitan Revolution. These areas in turn anchor a cultural arts scene.

These districts “draw from the best innovations in both industry clusters and place-making strategies to create well-defined communities packed with resources for firms, entrepreneurs, innovators, researchers and residents.”

Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley

Smart states and municipalities use a variety of incentives to upgrade commercial districts and invest in the small businesses that are the foundations for community. These programs entice locals with higher education to stay and start a business. Toronto, Canada uses a “Business Improvement Association” scheme. Allentown, Pennsylvania utilizes the state’s “Neighborhood Improvement Zone” designation, which gives companies investing in downtown tax breaks. This led to development of a sports/concert complex which attracted other, smaller businesses to the area. All these strategies contribute to growing smart cities.

Good area schools mean families will want to stay, and higher education – at least community college – and technical schools or enterprises like Bitwise train a local workforce, making a location even more appealing to relocating businesses. Amenities like publicly accessible waterfronts, sports teams and nearby recreation pull people together in a sense of civic pride, despite an increasingly politically polarized nation.

A New Era of Digital Infrastructure

The promise of smart cities remains that they will reduce the friction and hassles of everyday life and make urban areas a nicer place to live, but advanced technologies are allowing planners to envision an even more connected, autonomous, smarter city than ever before. Imagine residents take autonomous, constantly running transit to the store, buy what they need without standing in a checkout line, enter hotels or office buildings or gated communities without keys, with the help of facial recognition technology (FRT).

Using technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), 5G wireless internet and blockchain management, smart cities will use AI-driven technologies to adjust traffic lights based on real-time need to ease congestion, monitor pollution, waste management and utility usage, run transit networks, surge resources to areas during an emergency and make it easier for law enforcement to locate criminals. Residents can hop online to contact schools or access government records; city services are available by app. Cities with “smart grid” electricity are better able to manage and conserve electricity and integrate renewables, especially during fluctuations. Ditto smart water systems that can automatically detect leaks or disease, for instance.

We are bearing witness to…the early days of a variable and distributed generation revolution.

Gretchen Bakke

China’s Smart City Initiative

China is at the forefront of smart city-building, developing whole packages of solutions to connect smart city systems and users. Within China, the government is building smart cities from scratch. The Xiongan New Area south of Beijing is one such project, built for a projected five million residents.

Since 2012, China has invested massively in smart city technology, developing an estimated 400 smart cities by 2018. While Chinese technology automates traffic, police and fire services, it also heavily emphasizes crime prevention and maintaining social order. In fact, China often refers to these cities as “smart-safe cities.” Chinese companies market these systems to cities and states around the world, offering low-interest loans to build them out. As impressive as these mega-projects are, some of these massive developments will fail. Businesses would do well to analyze their underlying strengths – the geographical “bones” – when considering investments.

At home, China is building a massive surveillance infrastructure that tracks movement, payments, faces and even voices, often through social media apps like WeChat and TikTok developed by private companies but accessible to officials. Companies using FRT for employee entrance routinely share their data with law enforcement.

In China, urban planning projects are decided on by the central government, then implemented by local government without much input from them, an extension of authoritarian control. In contrast, European and US cities implement smart city plans primarily through the leadership of strong mayors and through an open civic process. Yet private companies also develop IoT and facial recognition technologies in western countries. Their incentive is to monetize the data they collect.

China’s dictatorship is updating itself with the tools of the 21st century.

Kai Strittmatter

Transparent City Planning

Every city has to figure out what its main problems are and devise solutions, integrating technology and inviting citizen engagement. To remain resilient in the face of climate change or unforeseen disasters such as a pandemic, and to manage competing priorities of residents, cities make plans to handle expansion, transit, traffic and other moveability needs including the delivery of goods, fire-fighting, law enforcement, public amenities such as parks, schools, libraries and recreation centers, and the management of various utilities: the electrical, water and gas systems. Some cities, like Chatanooga, Tennessee, install public Wi-Fi. But what the smartest cities have in common is a dedication to engagement with residents so they feel connected to and responsible for what happens in their hometown.

The city has always been a laboratory for figuring out what works, in business, in government, in culture.

Anthony Townsend

In the normal course of doing business, cities accumulate a lot of data. Facial recognition enhanced closed-circuit video surveillance systems (CCTV) systems add to that data stream. Whereas in the past, documents such as permit applications, birth certificates and property transactions were stored in endless rows of file cabinets that were nonetheless publicly accessible, it wasn’t until they were digitized that public accessibility to data became a raw material for new businesses, an avenue for entrepreneurs to ferret out niche markets or understand new problems and their potential solutions. Seoul makes the enormous amount of data it collects available to businesses and individuals, spurring the creation of new tools and services. But all those data points are also a security vulnerability.

It is the strangely conspiratorial truth of the surveillance society we inhabit that there are unknown entities gathering our data for unknown purposes.

Jathan Sadowski

To a technologist, smart cities highlight urban virtues and eliminate or at least minimize their hassles. To an environmentalist, smart cities are the best chance to reduce the carbon emissions from cities by meaningful levels as urban areas grow. To many, smart cities offer relief to poor populations by extending access and opportunity into every neighborhood. To privacy activists, however, pervading surveillance and data collection is cause for concern, which is why Reichental and others emphasize that city planning done right must engage residents and other stakeholders. For best results, author Anthony Townsend argues in “Smart Cities: What Do We Need to Know to Plan and Design Them Better?“, cities must develop a digital plan that is transparent about what data it captures and how it is used.

When Google’s Sidewalk Labs built a pilot program in Toronto, a place that frequently makes the lists of most livable cities, it had to prove to residents from the beginning that all user data collected by smart systems were anonymized. The company developed tools so residents were informed when their data were collected. More recently, however, Amazon’s Sidewalk shared mesh network technology is being implemented for everyone who owns an Amazon Alexa or Ring device with an opt-in default – people will have to specifically turn off the capability on their devices.

These competing visions of what a smart city is and could be are translating into what might be a point of global contention, with an east/west divide on aspects of implementing 5G. Interoperability is crucial to maintaining a free flow of trade, migration and information across borders.

Read More:

Keinen Channel gefunden.