Our World Is Counterintuitive and Exhausting

Imagine a cubical-shaped pool with edges the length of a kilometer. The pool is filled with water up to the rim. There is a hole in the bottom that leaks 100 liters per hour. How long does it take for the pool to empty? A few minutes? An hour? Some days? Weeks? Months? A year?

I like asking that question during my speeches, and every time I get irritated reactions to its correct answer: 317 years. Equivalent to the amount of time needed for working out a citizen-friendly tax reform.

Note

Our columnist Vince Ebert speaks at congresses, conferences and company celebrations in German and English on the topics of success, innovation and digitization. Here you can hire Vince Ebert as a keynote speaker for your event.

The reason for our irritated reaction is that the result runs contrary to our intuition. That is one of many reasons why most people have difficulties with natural sciences. Scientific insights and findings are often counterintuitive. They don’t fit our natural expectations and contradict our gut feeling.

The Thing about Intuition

Here is another example: If you pierce a beer coaster with a straw and hold the coaster close above a sheet of paper and then blow through the straw, the paper sheet will not be blown away. The exact opposite happens: The air within the gap between coaster and sheet gets compressed, causing underpressure, the so-called Bernoulli effect. The underpressure lifts the sheet. This proves that you can make it to the top with a lot of hot air.

Great scientific findings lie almost always beyond our realm of everyday experience. They hardly ever meet our natural expectations.

Well, this is not to say that our intuition isn’t a fantastic gift. After all, it lets us sense pretty quickly whether the gang of adolescents that come our way in a dark alley is harmless or not. And we know instantly whether our new boss is cool or a jerk.

In his book Gut Feelings, psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer reports about a colleague who played his students a short video of an academic instructor who they didn’t know and asked them their opinion on the competence of the said instructor. To his astonishment, his students’ ratings matched those of students who had been taught by that instructor for a whole semester.

We have perfected these impressive qualities over millions of years of evolution. When a Homo sapiens ran into a stranger at a water hole in the Stone Age, he had to answer a few fundamental questions instantly: Male or female? If female: Ready to procreate or not? If male: Friend or foe? If foe: Stronger or weaker? In a fraction of a second, he had to make his decision. Or there would be nothing left to decide. No meeting, no counseling, no mediation, no call-a-friend. 300,000 years ago, it came down to one question: Sex or war? And then came Starbucks. Now we have to take five to eight fundamental decisions to get a stupid cup of coffee. Soy milk? Almond? Frappucino? Double shot? Latte? Caramel syrup?

Nonetheless, most modern-day clever strategic decisions are based on an entirely different thinking pattern than our primal ancestors. Whether it is about developing a new system software, handling a pandemic or simply our retirement plan: In the 21st century, we have to analyze our decisions on a much broader, bigger scale.

Time Will Tell

We have to plan, construct and sift through enormous amounts of data material. With the help of statistics, we calculate risks and opportunities and immerse ourselves in detailed scientific studies. And more often than not, the result of this laborious and tiring process is the exact opposite of our original intuition. How awfully exhausting our modern lives are!

To recognize a good friend from behind and at a distance of 60 meters is easy for us. Even for a supercomputer, this is still nearly impossible. Because a computer has no friends, but it can multiply 746 x 238 in a split second. A person who can do that usually doesn’t have a good friend either.

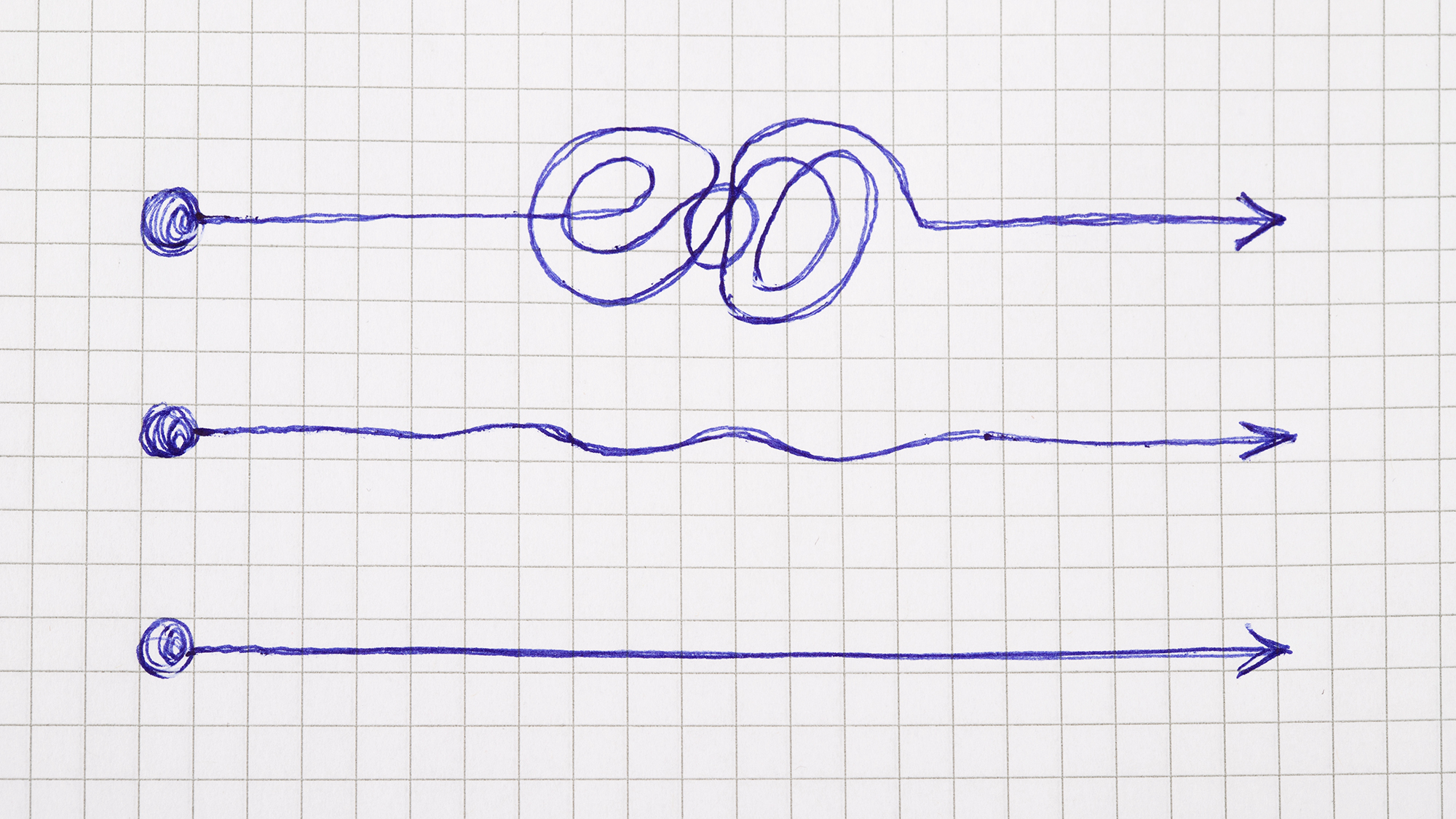

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman has been dealing with this human dilemma in his research for decades. He assumes that there are two basic kinds of thinking: a) intuitive thinking and b) rational thinking. The problem being that our intuitive thinking comes up with conclusions extremely quickly, long before our rational thinking even had time to warm up. That is very useful when hanging out in a cave and suddenly a saber-toothed tiger sticks his head in. Today saber-toothed tigers don’t present much harm anymore. Nevertheless, our brains fire up the exact same panic mode at the sight of insurance agents and used-car salespeople.

Therefore, this is my advice: If you have time to decide, try to quiet your intuition and instead let your rational side take over. That will take longer and is sometimes quite strenuous, but your brain will reward you with a pleasant surprise.

For further reading on the topic, Vince recommends the following from our knowledge library:

A Structured Approach to Strategic Decisions

MIT Sloan Management Review Read SummaryPhoto: Frank Eidel