New Digital Tools Change the Way the World Tackles Poverty

Over the past 30 years, prosperous countries and international organizations like the World Bank evolved a different way of thinking about the poor and alleviating poverty. For decades, economists like Jeffrey Sachs, encouraged by early successes, advocated a kind of austerity “shock therapy” for poor economies emerging from the shadows of dictatorships and centralized governments. But economics professor Mark Blyth makes the argument in Austerity that in many, if not most cases, calls for austerity to repair the debt crisis a nation faces is in fact “a transmuted and well-camouflaged banking crisis.” It becomes a national crisis when governments prop up their banks.

Taking on more debt to cure a debt problem seems counterintuitive, however, austerity is hazardous because effects are felt differently among different socioeconomic sectors, it stops the flow of money vital to repair economies and stops it everywhere, all at once. UN Special Rapporteur on Poverty Olivier De Schutter said the poor bore the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic due to years of austerity programs resulting in a lack of resilience in many nations’ economies. He also noted lack of universal health care access and $100 billion diverted from investments in emerging markets made the problem worse for the poor.

Digital Transformation Widened the Wealth Gap Between Rich and Poor

The globalization of trade and the digital revolution benefited countries unequally. Wealth gaps between the rich and the poor widened geometrically in the digital era. Columbia professor and former UN adviser Jeffrey Sachs examined global economic development in his acclaimed The End of Poverty. Originally a staunch austerity advocate, Sachs came to the conclusion that many of the global poor are not able to improve their lives without continuous aid from more well-developed nations. One of the primary ways he saw to liberate resources for countries to spend on services for their people was debt forgiveness, and he and world institutions favored large infrastructure projects like building roads or waterworks or schools to connect the remote poor to the world.

If the poor had access to capital – including resources, infrastructure and education – they would have the surpluses they need to think beyond mere survival to building wealth. In The Ages of Globalization, Sachs notes the threats to the poor from digital transformation include rising environmental harms due to pollution and burning fossil fuels, and increasing automation displacing workers.

Many of the world’s poorest countries are severely hindered by high transport costs, because they are landlocked; situated in the high-mountain ranges; or lack navigable rivers, long coastlines or good natural harbors.

Jeffrey D. Sachs

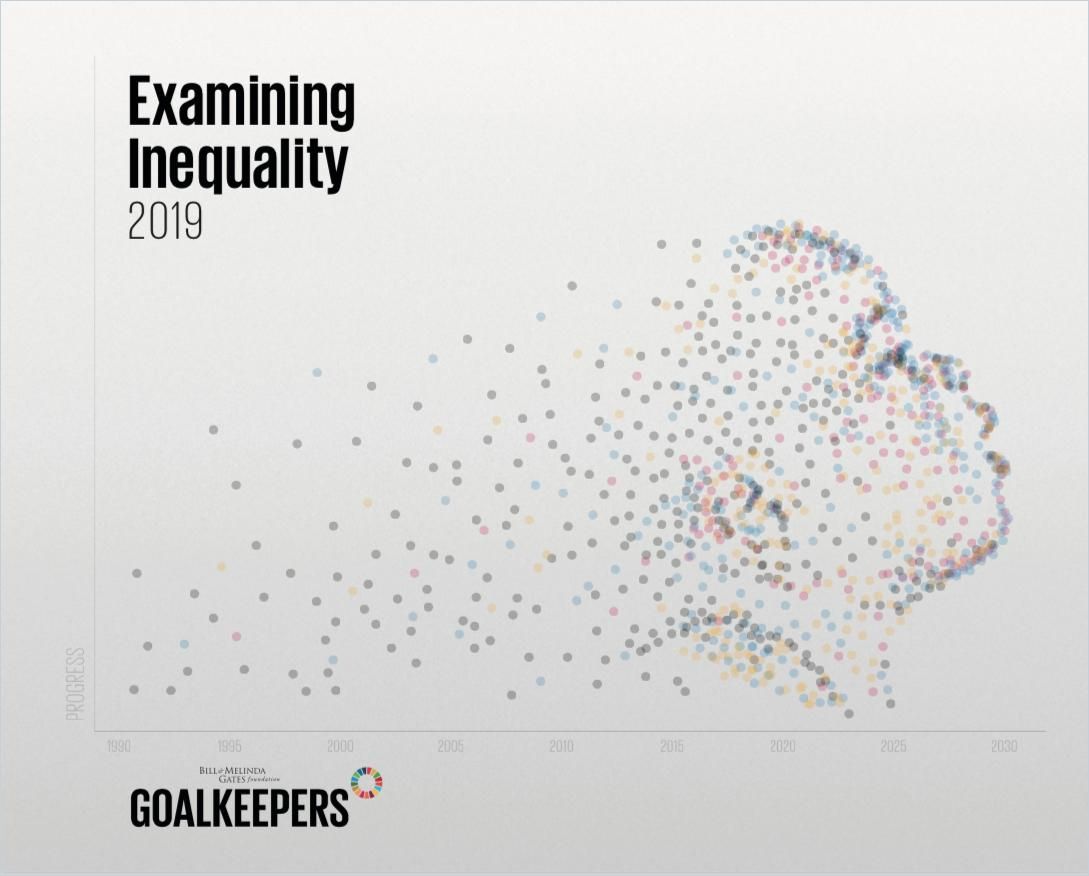

Bill Gates and Melinda Gates concur that geography, as well as gender and access to technology make a large difference when it comes to the benefits of globalization. In “Examining Inequality,” they explain why they focus their efforts on bringing education to the poor in order to help improve their future prospects.

For instance, girls in sub-Saharan Africa generally stop being educated in their teen years, and thus are less prepared to get a job. Customs and cultural prejudices against women need to change too, but closing the gap in education between the genders can improve equality as well as circumstances for women and their families.

Climate change is caused by the actions of richer countries, but the most vulnerable people in poorer countries are feeling it first.

Bill Gates and Melinda Gates

Sachs’s former approach favoring intensive infrastructure projects has had critics all along. Journalist Nina Munk claims in The Idealist that these top-down, capital-heavy projects yielded lackluster results. Though implemented with the best of intentions, building a school in Dertu, Kenya, in one of Sachs’s “Millennium Villages,” ultimately failed to offset the town’s lack of electricity and water.

Loans to farmers without accountability ensured their default. Add to that deep-seated official and unofficial corruption, misappropriation of funds and “refugee syndrome” which resulted from programs that incentivized living in UN-run camps over self-sufficiency. Ultimately, these projects were money pits that did nothing to alleviate poverty.

Broken water pumps, half-finished health care clinics, abandoned housing blocks, roads that lead nowhere…Africa’s strewn with the remains of well-meaning development projects.

Nina Munk

Investing in the Poor

Enter economics professor and Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, “banker to the poor.” Like Sachs, he agreed the biggest problem for the poor was the lack of capital that might allow them to build wealth. The poor can’t invest or save, which would help them pull themselves out of poverty. Part of the problem was, whether as a fan of austerity or stimulus, those theorizing about the poor didn’t spend a lot of time in their company. Yunus set out to understand firsthand the seemingly intractable problems they faced.

Instead of funding large infrastructure projects with dubious likelihood of their benefits trickling down to the poorest of the poor, Yunus found that granting microloans directly to the poor to invest in their own enterprises yielded outsized rewards. He founded the Grameen Bank and other enterprises to do just that. He discovered women were better loan risks than men, more likely to spend extra money to improve the lives of their family rather than themselves. In Creating a World Without Poverty, Yunus lays out his vision of capitalism working in a way that includes and benefits the poor, by including them in markets. He talks about “social businesses” – similar to social benefit or B Corporations – which emphasize the “triple bottom line” of people, planet and profits. A social business needs to be financially sustainable, but takes healing social ills as its purpose along the way.

Social business must be an essential part of the growth formula because it benefits the mass of people who would otherwise be disengaged. And when people are energized, so is the economy.

Muhammad Yunus

To Yunus’s way of thinking, when nations make sure resources reach the poor and not just the wealthy, the disadvantaged may participate directly in market economies that lift all boats. In A World of Three Zeroes, Yunus sums up the Grameen model of microloans and views it within the framework of a globalized, interdependent economy. As of 2017, Grameen Bank lent $2.5 billion annually to the poor, mostly to women, and enjoyed a 98.6% rate of repayment. Over the years it has helped more than 300 million people find a path out of poverty.

Yunus points out that technology innovators usually market to the affluent and then, once successful, iterate for the poor. Smartphones and online platforms have greatly eased the way for social benefit companies as well as brought direct help and powerful low-cost resources to the poor.

To me, changing the quality of life of the bottom 50% of the population is the essence of development.

Muhammad Yunus

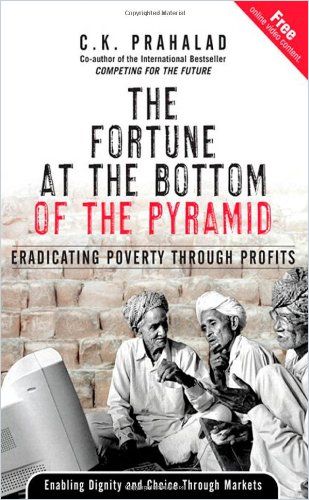

Marketing to the “Bottom of the Pyramid”

Author C.K. Prahalad calls this market segment the “bottom of the pyramid” (BOP), and explains how to engage the poor for profit. With a change in mind-set to market directly to the poor rather than via governmental aid projects, and the extension of laws to include protection of the poor and their growing assets, companies might realize profits at the BOP while reducing the corruption that drives up costs and misery for the poor in the first place. In “The New Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid,” innovation expert Deepa Prahalad updates her father’s now classic advice: The poor do not need charity so much as they need to be included in markets, so they can participate in improving their own lives. She particularly highlights the profound changes that the cell phone has brought to the lives of the world’s poorest.

With a smartphone, farmers can check on the fair market prices of their goods. Along with being able to pay their bills, people can voice their opinions online and participate in local decisions that affect them. They can find jobs via digital platforms. Brookings think tank noted the success the Togo government had transferring digital cash payments to its citizens during their pandemic lockdown using cell phones combined with several data sorting methods. Businesses can now easily analyze the data points of these emerging markets to provide attractive products and services, or to provide a selling platform for local merchants. Businesses have every reason to be optimistic that they will do well by also doing good. This is a sea change from the trickle-down school of thought on development in poor countries.

The traditional view of needs explains very little of what is being adopted and purchased at scale in emerging markets.

Deepa Prahalad

In Taming the Sun, clean energy expert Varun Sivaram describes how mini-grid solar electrical systems are now affordable to the rural poor. In East African countries, entrepreneurial companies build out solar installations, then collect payments via cell phone from ratepayers in a pay-as-you-go program.

These monthly contracts can be used as securities to attract additional investment to continue building out solar. What was once a problem that looked like it required huge infrastructure to achieve – getting electricity to the poor – is solved with new technologies and innovative market solutions. Sivaram cautions that government investments in electricity should be careful not to compete with these off-grid endeavors. However, they can eventually be linked together or connected to a national grid. Chief technology officer for Microsoft Kevin Scott describes in Reprogramming the American Dream how the integration of artificial intelligence in business, though it might take away some jobs, will provide opportunities for others, and bring those opportunities to where people live already, rather than just a few prosperous regions.

In The Prosperity Paradox, rather than pushing projects or innovations on the poor, authors Karen Dillon, Efosa Ojomo and Clayton M. Christensen recommend that companies develop products and services that people can “pull” into their lives, to see if they’re viable. Food manufacturer Tolaram created inexpensive and easy-to-make noodles and marketed them to great success in Nigerian urban centers despite there never having been a market for noodles there before. Here’s some guidance for businesses to think innovatively about BOP markets:

- Target “nonconsumption” by either adapting higher-end products or creating new markets.

- Use technologies to improve manufacturing efficiencies and lower consumer prices.

- Innovate value by bringing your offering to where the people are.

- Remain flexible and willing to learn, which is why executive support is essential.

If we create a market that successfully serves a growing population of nonconsumers, that market is likely to pull in many other resources an economy requires.

Karen Dillon, Efosa Ojomo and Clayton M. Christensen

Additional reading:

Learn more about the trends changing the world:

Find out more about B Corporations, conscious capitalism and CSR programs that inspire: