Declaring Human Rights

In 1944, the United States, Britain, China and the Soviet Union established the United Nations (UN) in the aftermath of the authoritarianism and carnage of World War II, as a mechanism against future wars. It was the world’s response to atrocities against humanity, a collective “never again,” which affirmed the central principle of universal human rights. Before that, human rights had a brief but dramatic history, the principle growing in acceptance throughout the 18th century and culminating in the American and French revolutions, grounded as they were in a celebration of individual liberty.

The founding documents of these new republics established the idea that human rights are universal, something people have by virtue of being born human, rights that transcend governments. Despite the lofty pronouncements of universality, in practice “human rights” at first applied to white men of property. Neither America’s nor France’s revolutionary statements of human rights included people of color or religious minorities or women. In fact, when Olympe de Gouges sought to include women in the French revolution, she was charged with treason and executed for her efforts – but it was a start.

An International Agreement on the Fundamental Dignity of Human Beings

UN member countries commissioned a group chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt to develop a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to lay out the rights all countries of the world affirm for their people, and to guide the organization in assessing how various nations treat their citizens. Sixteen member nations sent delegates and all played a part in the language and framework the UN adopted.

Hansa Mehta of India made sure women were included. Carlos Romulo of the Philippines contributed language to affirm the rights of former colonial nations. Chile’s Hernán Santa Cruz focused on the social and economic rights of people in addition to their civil and political rights. Peng-chun Chang of China was Vice Chair of the Commission and ensured the Declaration included all religions and belief systems. Other delegates contributed valuable ideas and language, and the Commission solicited input from the world’s foremost thinkers including Mohandas Gandhi, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Chung-Shu Lo.

The group zeroed in on 15 areas of universal agreement: the right to live, to work, to own property, access to education, information and health, freedom of thought, speech and self-expression, the freedom to participate politically and to expect fair legal procedures, the rights of citizenship, the right to “share in progress,” and the right to “rebel against an unjust regime.”

The chief obstacle to unanimous approval of the Declaration was…its potential for legitimating outside interference in a country’s internal affairs.

Mary Ann Glendon, A World Made New

The United Nations adopted the Declaration on December 10, 1948, without objections, and each year the countries of the world celebrate its anniversary. Since 1948, 90 countries have crafted human rights clauses in their constitutions inspired by its ideals and language.

Human Rights Beget Peace

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights begins, “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…” It goes on to lay out in a series of Articles all the ways in which the principle of human rights infuses personal, communal and political life within democracies. The Declaration emphasizes the values of multiculturalism and democratic processes as the most effective way to maintain global peace. Alone, it has no legal heft, but it packs a moral punch.

Covenants translate the Declaration into law: The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) are the two main ones. But it took another 28 years, until 1976, before ratification by enough member states put it into effect. These Covenants oblige member countries to intervene in certain ways when governments do not accord their citizens equal concern and respect; most often, cases of genocide trigger implementation.

The United States didn’t ratify the ICCPR until 1992 and signed, but hasn’t yet ratified, the ICESCR. The United States remains reluctant to ratify human rights Conventions unless already consistent with its federal law. Human Rights Watch calls the United States out on its deteriorating human rights records on immigration, racial discrimination, income inequality and a host of other issues.

The international politics of human rights is largely a matter of mobilizing shame.

Jack Donnelly, Universal Human Rights

Although in principle all nations affirm the fundamental dignity of human beings, categorizing different rights has made it easier in some cases for regimes that might violate human rights to deny one or the other class of rights. China has yet to ratify the ICESCR.

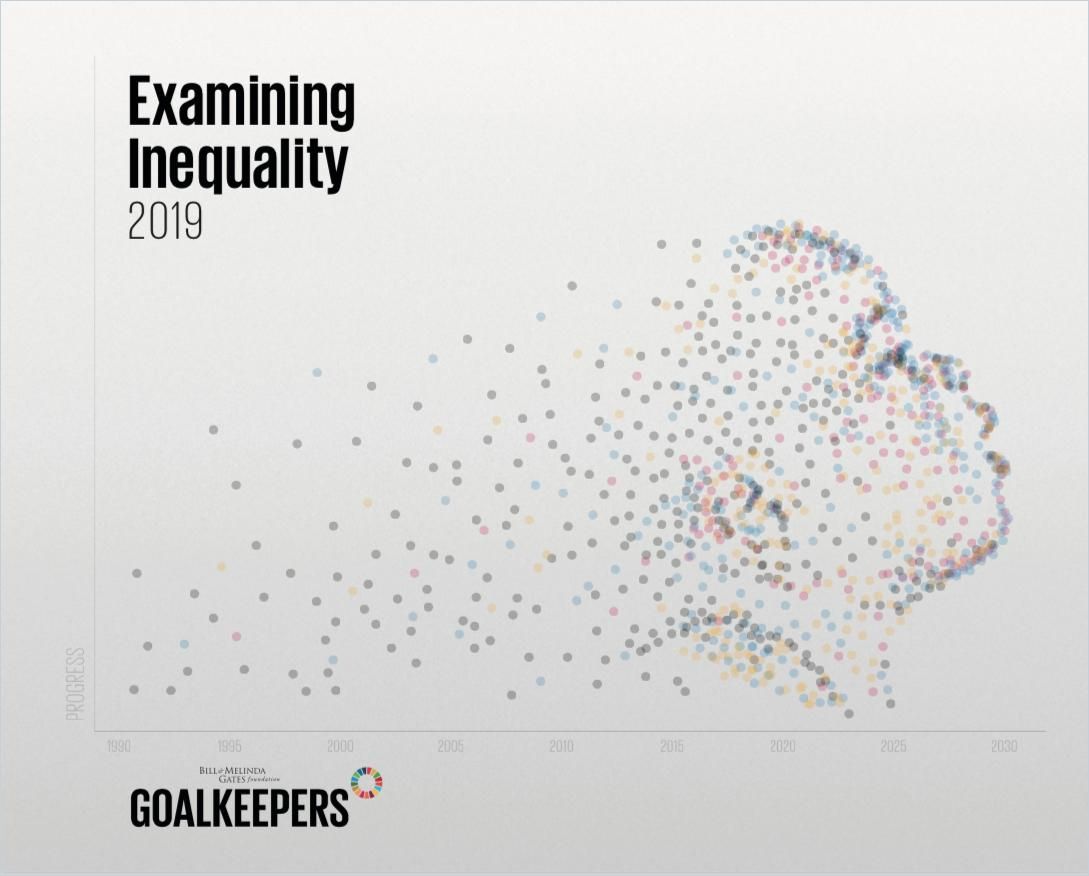

The UN Human Rights Council regularly reviews member state records on human rights. International treaties also provide oversight and non-governmental organizations focused on particular issues such as genocide, slavery, torture and discrimination include more and more marginalized groups under the umbrella of human rights protections. Countries that devise social safety net programs mitigate some of the inequalities often caused by free markets while preserving justice and human dignity.

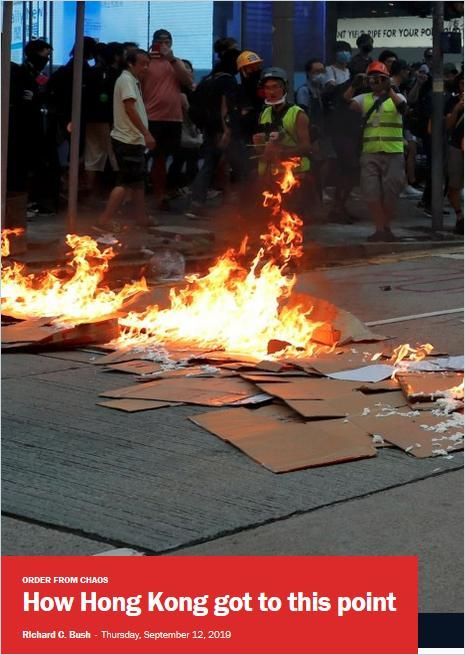

China’s Growing Rejection of Human Rights

China signed the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as part of its agreement with the United Kingdom on the transfer of Hong Kong sovereignty, affirming it would stay in effect for Hong Kong, but it remains unratified. The country met growing pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong with brutal suppression followed by little international condemnation. Many fear its actions in Hong Kong test the waters for Chinese aggression in Taiwan and other territories.

Is It Too Late to Save Hong Kong from Beijing’s Authoritarian Grasp?

The Guardian Read SummaryChina has long been suspicious of an international standard for human rights, framing it as a Western construction and an imposition on Chinese sovereignty. According to Human Rights Watch director Kenneth Roth, China now actively campaigns against human rights principles and the institutions that uphold them. Russia similarly seeks to undermine the global institutions in place to protect human rights.

The Chinese government suppresses domestic dissent; it established a public surveillance protocol unprecedented in its reach. Facial-recognition and other intrusive surveillance methods track people’s movements.

China has particularly targeted Xinjiang, an area in the northwest of the country where upwards of 13 million Muslims live. China has detained over one million Muslims in detention centers for the purpose of “reeducation.”

At the same time, China uses its power and influence at the UN to prevent action against human rights violations globally, including airstrikes against Syrian and Yemeni civilians, ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, and economic devastation in Venezuela. China refuses to allow international scrutiny over its own human rights violations. The United States imposed sanctions prohibiting the regime from buying some US technologies implicated in human rights abuses.

If China succeeds in leaving the UN toothless on human rights, all will suffer.

Kenneth Roth, director of Human Rights Watch

European countries remain focused on internal affairs, and the United States under Donald Trump is uninterested in defending human rights. Chinese investment globally is powerful incentive for many to remain silent in the face of human rights abuses. Even companies such as Volkswagen and Marriott self-censor for fear of offending Chinese business partners. Hollywood producers edited out the Taiwanese flag Tom Cruise wore on his jacket in his Top Gun sequel. Fifty-seven member states of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation likewise remain silent about China’s concentration camps.

Coming Soon to the United Nations: Chinese Leadership and Authoritarian Values

Foreign AffairsChina is flexing through the United Nations to push its own policy interests, jeopardizing the historic role the UN has played in protecting human rights. Only countries working in concert can confront these abuses and begin to change them.

Only global cooperation can solve many of the world’s most pressing problems. It’s time to reform international institutions so they’re equipped to deal with multiplying international threats such as pandemics, financial upheaval, climate change, international and cybercrimes, and migration. Geneva conventions governing warfare need updating to account for autonomous and automated weapons technology.

Business Too Must Affirm Human Rights

83% of senior executives in a 2014 global survey said they believe business has a role in protecting human rights. But it’s a tricky needle to thread. Business leaders must weigh community relations and stakeholder expectations against long and short-term costs. When US companies in Hong Kong initially condemned pro-democracy protesters for closing down the business district, they were excoriated by human rights groups around the world, damaging their reputations.

Ultimately, business leaders look to government regulations and international treaties to guide their company’s behavior. Obviously, stability in the world order benefits business.

Democratic governance is only as effective as the people willing to uphold it. With a new US administration already planning to rejoin international obligations and defend human dignity, now is the time for nations of the world to reaffirm the universal principles of human rights as the foundation for global agreement and cooperation.

Read more about the United Nations and areas of international concern: