Climate Change Solutions Gone Wild

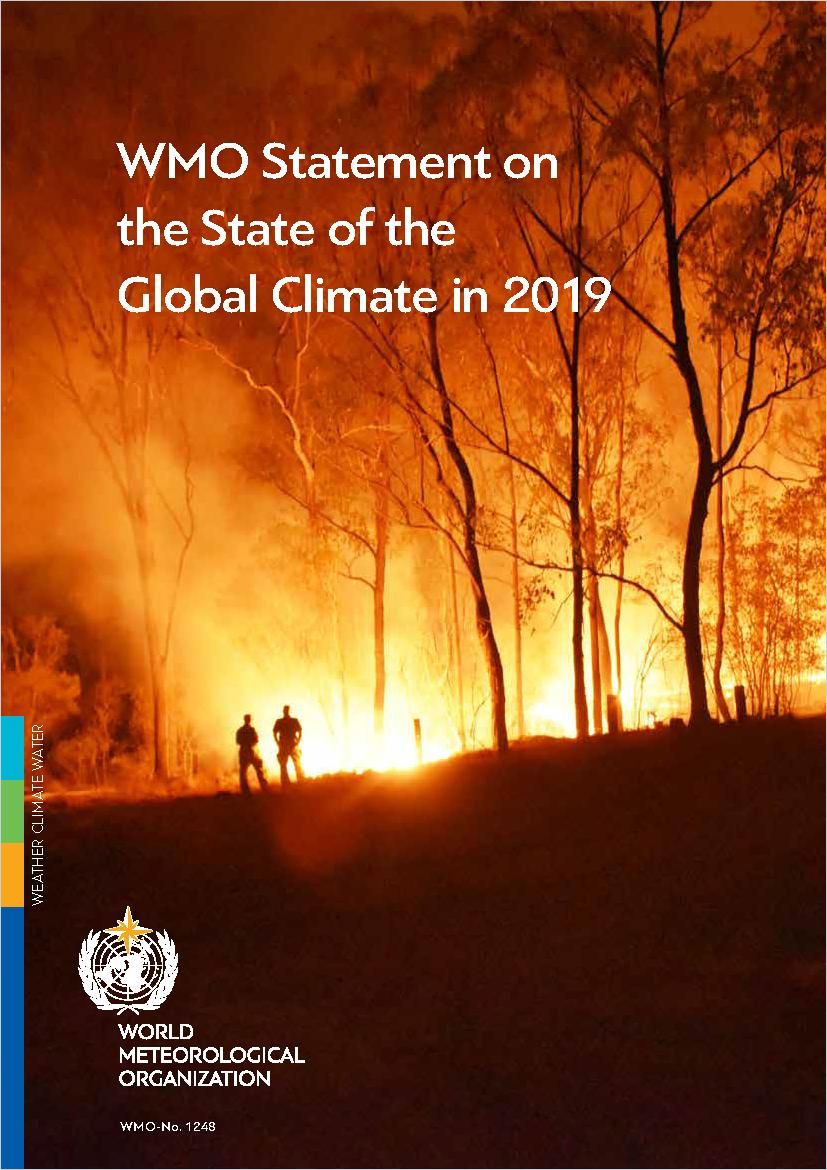

The world already bears witness to the existential threats posed by climate change: out of control wildfires, devastating floods and storms, rising sea levels, and a steep decline in biodiversity. Calibrating climate change is a moving target, with scientists constantly sifting through new data and revising their recommendations. Taking no action puts the world on track to exceed 4oC before the end of the century, reaching “climate departure” by 2047, where extremes become the new normal, with non-stop record-breaking heat waves and super-storms. The threat is existential. Thus, most climate scientists recommend doing whatever is possible to be sure temperatures don’t exceed a 1.5oC rise above pre-industrial numbers in order to avoid the worst of climate change catastrophes. The world needs quick answers and action.

WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2019

World Meteorological OrganizationWhen it comes to removing carbon emissions from the climate catastrophe equation as quickly as possible, scientists and policymakers focus primarily on transitioning to a carbon-neutral global economy built on renewable energy and negative-emissions schemes that draw down carbon already in the atmosphere, sequestering it where it can do no harm. Businesses tend to focus on unperfected high-tech solutions like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) systems that require enormous areas of land and lots of capital or air scrubbers, which are also costly and not up to the enormous scope of the task. The transition to a zero-carbon economy is happening more slowly than foreseen, while climate change impacts accelerate.

Instead of cutting-edge tech solutions, environmentalist George Monbiot and many climate scientists favor a low-tech solution already proving its worth: letting nature restore depleted landscapes.

Trophic Cascades with Benefits

Monbiot calls such restoration “rewilding.” The idea is to re-introduce flora and fauna native (or close to native) to a depleted area and let nature take its course, rebalancing the ecosystem. It’s based on James Lovelock’s “Gaia Hypothesis” that the Earth is an interconnected living organism capable of healing itself.

When scientists reintroduced endangered gray wolves to Yellowstone Park in Wyoming after being absent for 70 years, they quickly worked to check a sickly elk population too large for the park to sustain, causing a trophic cascade – a ripple of benefits throughout the ecosystem. The elk stopped grazing in the valleys, where they were easy prey, which allowed plants and trees to grow back, which attracted birds and smaller prey animals. More stable river banks encouraged beavers to build more habitats, perfect places for otters and fish to rebound. Coyotes retreated. Twenty-five years later, experts consider this experiment in rewilding a resounding success, barring a few ranchers convinced without much evidence they are a danger to their stock herds. Yellowstone’s success was a big selling point in Colorado, which recently voted to reintroduce wolves in the state.

Trophic cascades reflect the complexity of nature, and it’s in that complexity that nature builds its resilience.

In addition to sequestering carbon efficiently, rewilding works to protect the world’s biodiversity. Whales in the South Pacific work in a similar way, as a trophic species, to anchor ocean biodiversity and sequester carbon at the ocean floor.

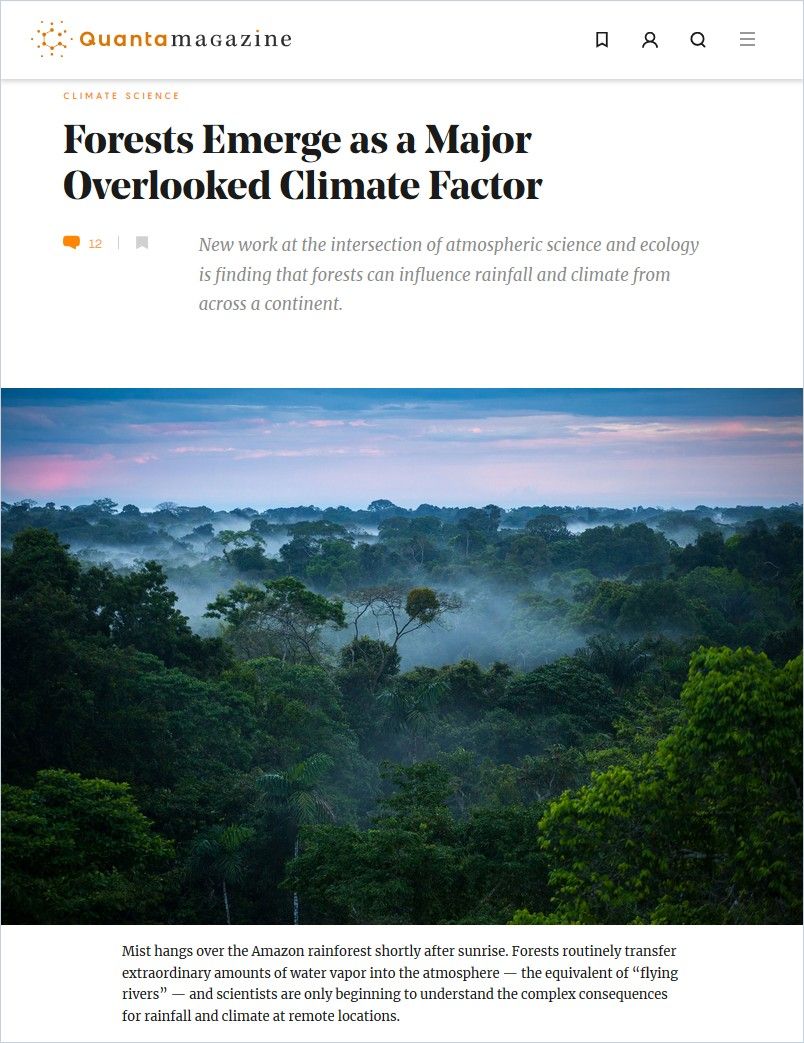

Sometimes You Can’t See the Forest for the Trees

Many countries signed up for the Bonn Challenge in 2011 to convert large areas of their lands to forest, a total of 350 million hectares globally by 2030. Experts predict these lands can draw down and store 25% of the carbon the world needs to meet its carbon reduction goals. For many, though, “forests” was a term too broadly defined. Member countries pledged a mix of restored natural habitats, agroforestry, which preserves trees that work symbiotically to protect and nourish crops, and plantations. While plantations and agroforestry have their pluses – they boost local economies and are more sustainable approaches to agriculture – they don’t do as good a job soaking up CO2 as natural landscapes.

Monocultures make ecosystems more vulnerable to disease and depletion, less complex and therefore less resilient. For commercial plantations, harvest time releases all that stored carbon, erasing benefits. Restored forests sequester carbon 40 times more efficiently than plantations, and they hold onto it over decades, so long as they’re protected.

A full two-thirds of all lands pledged for restoration in the Bonn Challenge are in fact slated for plantation use. Brazil pledges to more than double land dedicated to plantation crops, and counts this towards its reforestation goal, decidedly not in the spirit of the Bonn Challenge. In this way, official climate goals might be inadvertently incentivizing the destruction of existing forests. This kind of system gaming is rampant among countries when it comes to climate change commitments. Solutions built on a foundation of unchecked development and endless market expansions will fail.

Bonn Challenge countries need to strengthen their terminology as well as their commitments to restoring more natural habitats in addition to their plantations or agroforestry projects.

A Caveat

Climate scientist Abigail Swann is doing a lot of work to determine the impacts of forests on climate change, and the effects of their eradication as well. It turns out you don’t want to encourage forests in northern climates because they diminish the positive albedo effects of ice reflecting heat away from the earth. Forests growing in what was once frozen land may wreak the same magnitude of environmental damage as do rising sea levels from melting glaciers. Also, according to Swann, excess CO2 in the atmosphere may cause forests such as the Amazon to stop releasing water vapor, which would cause tree systems to die off, with devastating consequences.

Monbiot specifically suggests focusing on rebuilding equatorial rainforest systems across the globe, relying on large plant-eating mammals to spread seeds of trees most efficient at sequestering carbon. Temperate forests also act as efficient carbon sinks, so long as stewards introduce apex carnivores to keep herbivore populations in check.

Restoring coastal mangroves may bring the biggest, most immediate carbon savings of all.

Generally speaking, the effects of forest systems on climate change in near and far terms needs more study. Forests replacing frozen tundra in northern climes also release carbon and methane long stored beneath permafrost. Successes in Yellowstone and elsewhere inspired scientists in Russia to slow down permafrost melt by restoring these areas to vast grasslands, better able to reflect sunlight, and also preserve permafrost. Ancient grasslands were once kept in check by woolly mammoths. These scientists are genetically engineering a mammoth cousin, adapted from the Asian elephant.

Resurrecting the Woolly Mammoth and Other Climate Moonshots

Aspen InstituteThe experiment is extreme, but the stakes are particularly high, since the Arctic is warming at faster rates than expected. Average temperatures matter, but so do the peaks and valleys. Rewilding is only useful if part of a larger, more comprehensive effort to remove carbon from global economies and from the atmosphere in other ways.

Preserving Biodiversity

At a UN biodiversity summit in September 2020, 64 nations pledged to protect 30% of the world’s lands and oceans by 2030 in order to stem runaway species loss and environmental degradation. The fact is the natural world supplies humans with everything they need to live: soil, water, oxygen, plant and animal life. Animals pollinate crops and control pests. Rock formations and other substrate filters fresh water. Photosynthesis causes plants to grow. Coastal lands protect communities against storm surges.

The list of nature’s benefits to humanity is literally endless, and science is just beginning to realize the ways being in nature enhances human well-being, including lowering blood pressure and positive changes in hormone levels and brain chemistry.

Humans depend upon the rejuvenating powers of nature as much as fresh water and air. Biodiversity is essential to a world that supports human (or any) life. Almost all economic activity relies upon nature. Experts estimate that, without efforts to reverse habitat loss, the world will lose $10 trillion in environmental services by 2050.

Restoring ecosystems – rewilding – is a way to meet multiple goals at the same time: sequester carbon, provide habitats to protect the world’s biodiversity and safeguard the valuable and indispensable services nature provides to people and planet. This is a goal only countries working together can meet.

Learn more about switching to carbon-neutral energy solutions: