FOCUS: Climate Change

A few days ago, Jonathan Watts, The Guardian‘s global environment editor, summarized what many had previously only thought and then rejected out of misunderstood shame: “The environmental changes wrought by the coronavirus were first visible from space. Then, as the disease and the lockdown spread, they could be sensed in the sky above our heads, the air in our lungs and even the ground beneath our feet.”

More specifically, he added: “As motorways cleared and factories closed, dirty brown pollution belts shrunk over cities and industrial centres in country after country within days of lockdown. First China, then Italy, and now the UK, Germany and dozens of other countries are experiencing temporary falls in carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide of as much as 40%, greatly improving air quality and reducing the risks of asthma, heart attacks and lung disease.”

He too, of course, mentions the tragic consequences of the pandemic – many thousands of deaths. But his focus is different, namely on the remarkable environmental effects that the coronavirus has engendered: a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. This phenomenon is something that activists, politicians and companies had only dreamt about before the pandemic, but it has (sadly, at enormous human costs) opened up a glimpse into a possible future without fossil fuels (but with marauding goats).

It is far from unlikely that this whole phase of partial scarcity, isolation and even self-sustainability will have a significant impact on how we deal with resources in the future, especially with our climate.

What progressive approaches to climate protection are there? What is feasible, what is not? And how much political assertiveness is needed – from societies and also from each individual?

What does it take to put an issue on the global agenda?

Let’s go back in time for a second. In August 2018, Greta Thunberg, who was 15 years old at the time, left her Swedish classroom and began a strike. What at first looked like a somewhat bizarre individual action, motivated millions of people around the world to take part in the following months. Whether in the world’s metropolises or in provincial nests whose names no one can spell correctly, the climate strike kept large parts of the world on their toes and put the topic of “human-made global warming” right at the top of the political agenda. Since then, not a few parliaments have been reassembled under green signs; elsewhere the forecasts are also pointing to change.

On Tuesday, December 2, Thunberg arrived in Lisbon after crossing the Atlantic Ocean on a sailboat, to attend the 2019 annual UN Climate Change Conference, known as COP25, in Madrid, where “29,000 visitors are expected over the next two weeks, including 50 heads of state” to “nail down some details left open by the 2015 Paris climate accord, including how carbon-trading systems and compensation for poor countries with rising sea levels will work,” as Foreign Policy put it. So, the debate about the role of humans and their part in the global warming of the last 100 years may be settled (to a large extent), and the public is aware of the problem. But when it comes to dealing with these facts and to define how to actively take countermeasures, things look different.

There are a lot of ideas for this. Initially, that’s good news. But when it comes to applicability and effectiveness, some ideas immediately lose their appeal to either politicians, companies or climate activists. Furthermore, as Michael Shellenberger explained in Forbes, many people, especially decision makers – be it in private or public, in charge of many or just oneself – are afraid of the future. And as sure as fear is a bad counselor in most situations, apocalyptic claims about climate change are misleading in the current debate. So, let’s tackle the most common ideas on counteracting global warming with links to the relevant knowledge in getAbstract’s library.

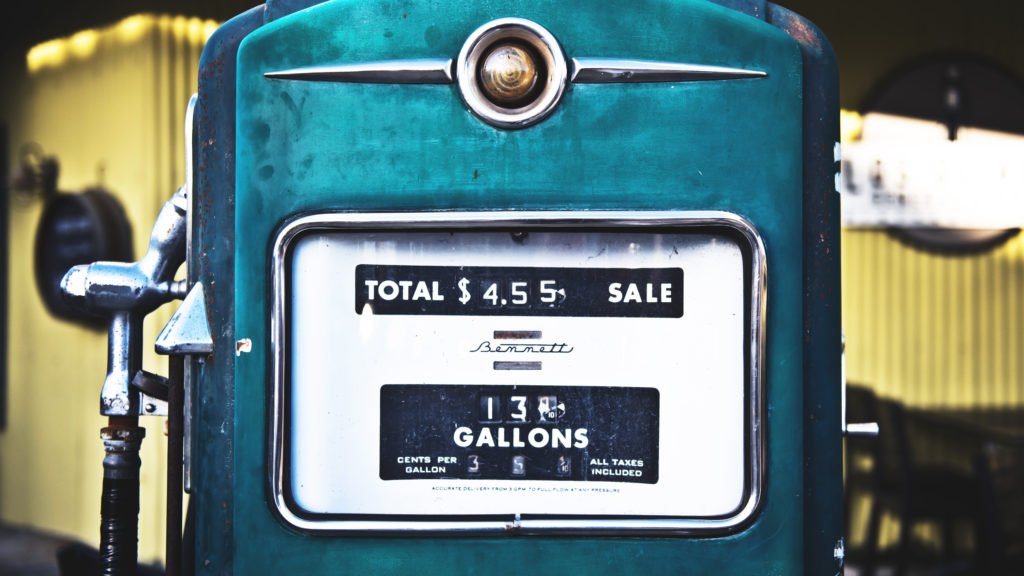

1. Should carbon dioxide emissions be taxed more heavily worldwide, i.e., made more expensive, and should this incentive tax be expected to have the hoped-for effect of reducing emissions?

Carbon pricing won’t work by itself, but it can reduce emissions by 26% if correctly implemented. In Designing Climate Solutions. A Policy Guide for Low-Carbon Energy, Hal Harvey, Robbie Orvis and Jeffrey Rissman argue that everything necessary to make the transition to a low-carbon economy already exists. The technologies are robust and the costs are low.

The only thing missing, they say, is the political will. Among other policies, they argue, carbon pricing “is technology-neutral and generates an efficient source of revenue, which can be helpful for accomplishing other policy objectives.” But: Policy makers should focus on results and not on selecting specific technologies. Policy entrepreneur Ted Halstead, for example, proposes a transformative solution based on the principles of free markets and limited government.

The bad news? Despite 42 countries and 25 sub-national jurisdictions already adopting carbon pricing schemes, carbon emissions have not decreased significantly. As Stanford scholar Jeffrey Ball argues in Foreign Affairs, carbon pricing has so far failed to produce the hoped-for emissions cuts. Even worse, the policy has given governments and companies the false assurance that they are effectively fighting climate change despite evidence to the contrary. Supplementary measures are needed to cut greenhouse gas emissions, such as phasing out coal, keeping nuclear power plants online, promoting clean energy technology, increasing fuel taxes – besides preparing for and adapting to climate change.

2. Is it likely that our economies will go down the drain in the process? And how effective can this strategy be anyway, if only some nations act while others return to business-as-usual?

Since Sweden implemented a carbon tax in the 1990s, the nation has increased its GDP by nearly 80%, while its emissions have fallen by 25%. Therefore, many experts believe that nations must proceed in concert to avoid the economic penalties of acting unilaterally.

Anyway, extensive analyses of optimal emission-reduction scenarios indicate otherwise: In a report from the Boston Consulting Group, their group of authors writes: “Contrary to widespread belief, countries that take ambitious action against climate change can benefit macroeconomically…Many businesses strongly endorse such action.”

Prospects are excellent that nations moving individually but decisively to reduce carbon discharges will bring about both a thriving environment and growing economies. Using proven technologies, reaching about 75% of their goals will cost the United States, China, Brazil, and Germany roughly 1% of their GDPs.

Important notice here, since we hear the following question all the time: But if you do nothing to counteract global warming, it’s “free” (AKA “won’t cost us, so it won’t ‘harm’ the economy”), right?

No. Because ongoing warming will cost the world’s societies and economies a lot more. How much? When predicting the cost of climate change, William “Bill” Nordhaus – winner of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences – argues that a 1°C increase will cost 0.5% of the GDP. A 2°C increase will cost 1%, 4°C will cost 4% and 6°C will cost 10%.

And these are most certainly conservative estimates. In Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet, climate scientist Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman argue that estimates could be exponential because climate change will reduce the rate of economic growth in many places. The present value of expected average losses through 2100 due to climate change amounts to $4.2 trillion, roughly equivalent to the GDP of Japan. Not to speak about likely reductions in food production, starving people, shortened lives, and destroyed ecosystems which can’t be balanced by producing better consumer electronics.

3. Is there any point in using bans, for example, to make individual types of mobility so unattractive that large parts of the world have to switch to more climate-friendly alternatives?

In the currently heated debate on climate, more and more political forces are calling on the leaders of industrialized countries to bring about social and economic change by banning “outdated” technologies and behaviors. The procedure, as simple and effective as it looks, has its pitfalls: If it is rigorously implemented, there’s a risk of political turmoil and protest. In times when large parts of the populations of western welfare states are already complaining about too much bullying, paternalism, and financial burdens, oil is poured onto the fire. Even if it comes to “friendlier” versions of top-down-directing human behavior – such as “paternalistic nudging” – the outcomes are, as law professor Anne van Aaken explains, mixed when it comes to effectiveness.

In addition to this political argument against far-reaching bans on technologies, there is one scientific argument above all: If one bans one technology (or its use) before another is really competitive, there is a risk of serious resource shortages and infrastructural bottlenecks that cannot be offset or can only be offset by enormous additional burdens. This applies to individual use (e.g. in rural areas, where people are generally dependent on affordable individual mobility, i.e., cars with internal combustion engines), but also to entire societies (e.g. national bans on nuclear and coal-fired power plants where alternative energies cannot yet cover demand).

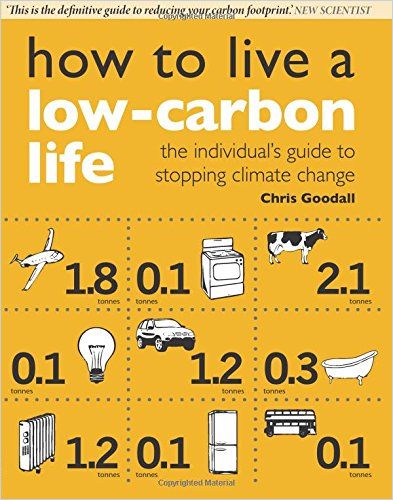

A better – and much more effective – way to drive technology change is social change: Individuals will make the difference! In Chris Goodall’s classic How to Live a Low-Carbon Life, he explains how you can reduce your carbon emissions from an average of 12.5 tons per year to three.

And, of course, politics can provide smart incentives to use better technologies additionally. This won’t incapacitate citizens; on the contrary, it could increase their choice and decision-making scope, open up new markets and ideally ensure “green growth”.

4. But when it comes to electric vehicles, for example, what’s the CO2 emissions impact within the industries behind battery-powered cars?

Well, there is currently no reliable way to assess the environmental life cycle impacts of electric versus conventional vehicles. However, the International Council on Clean Transportation reports that a typical European electric vehicle produces about half of the greenhouse gases that a conventional car produces during its first 150,000 kilometers of use. Factoring in driving conditions, such a car would “pay back” its manufacturing emissions in about two years. But most car batteries used in Europe are produced in South Korea and Japan – at plants where 25-40% of electricity is generated from coal. So, greener electrical grids are crucial for the effort to maximize electric vehicle life cycle emissions – and they will happen. More good news? Future lithium-ion batteries will undoubtedly be larger and less carbon-intensive.

5. So, let’s say I decide to change my habits: How about reducing (or even skipping) beef and other high-emission foods? The food industry is responsible for 31% of global CO2 emissions.

Well, let’s keep it short and simple here: Good idea.

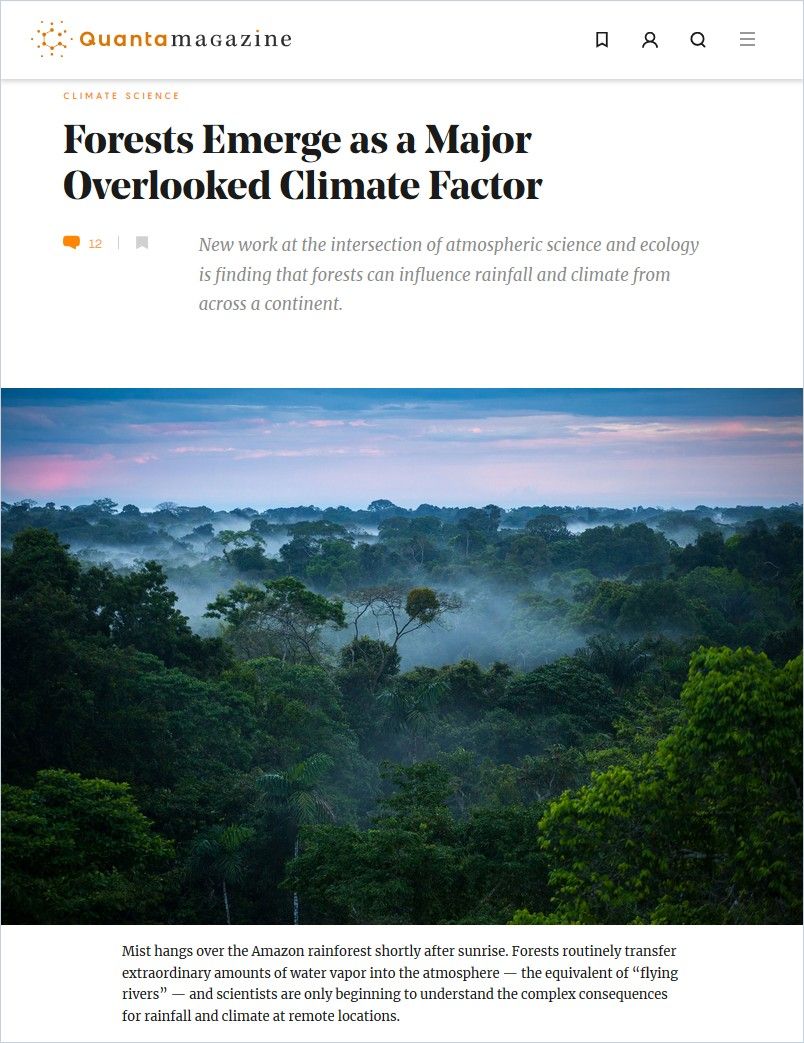

6. How about just planting a lot more CO2-absorbing trees around the world?

Indeed, forests are powerful biological engines which create “flying rivers,” points out Abigail Swann, whose groundbreaking work stands out in an elite scientific community studying the effects of forests on climate. Journalist Gabriel Popkin refers to her findings and aims to transform the landscape of perspectives on the role of plant ecosystems in climate change in his 2018 Quanta article. Other Negative emissions technologies (NETs) will help reduce global warming, too. One of the most promising is Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). In Science, Julia Rosen explains how it works.

7. Is there enough time to counteract global warming anyway?

In view of the inertia of many people and countries to date, this is not entirely certain. But perhaps we can borrow time to solve the problem in the future. Climate innovation activist Kelly Wanser explains possible fast-lane solutions (like, don’t shake your head immediately, “marine cloud brightening”) to buy scientists the time they need to reduce global temperatures permanently.