“Let’s Stop This Together”

It is day two of the general lockdown in Italy, where I’ve been living with my family since 2003. We’ve been receiving many inquiries from worried friends and family members, and it feels odd to say this in a moment of great uncertainty, fear and also widespread misinformation: But we are perfectly fine. Our family has been less affected than others. My husband and I work from home in any event. For reasons unrelated to the COVID-19 crisis, we have already been homeschooling our older daughter. The younger has been telelearning since March 5th, when all schools and universities were closed by government decree.

Just to be clear: None of us is taking it lightly at this point, nor are we trying to ridicule or even undermine the efforts to contain the threat. Thus far, there are 37 people who tested positive in Umbria, our adopted home in Central Italy. No one has died from the disease here. We live on a beautiful hill in the countryside, there’s fresh produce from the garden, eggs from our chickens and ducks, and we can go for walks in the woods whenever we want. From our point of view, things are not so bad, after all. The new tagline all over social media is “Io resto a casa, #fermiamoloinsieme” – I’m staying home, #let’s stop this together.

People are advised to curl up on their couch with a good book or favorite miniseries, avoid going to work or seeing friends for a coffee or meal and take it easy until April 3rd, when, hopefully, things will begin to go back to normal.

No Passeggiata

Most people seem to take it stoically. In Umbria we are used to “special periods,” and in many ways the situation is reminiscent of 2016, where we were kept on edge by two major earthquakes and countless aftershocks from August through December. Yesterday, I went to the nearby town of Spoleto to run a few errands. The place seemed like a ghost town. Bars are required to close at 6 p.m., and the Corso, where the Spoletini usually go for their treasured “passeggiata” – a walk up and down the main shopping street to see and be seen – was deserted. When I went to see a friend who has a car repair shop, he told me I was the second person to come in that day. Another friend with a shop for handcrafted leather and jewelery – same story. He is actually going to close up for now and stay home. At the post office and supermarket you have to pull numbers and wait in line outside. Security personnel allow you to enter only when another person is leaving the premises, to make sure that people stay at safe distances from one another. Yet people can’t help but make the odd harmless joke:

“You don’t want a face mask, do you?” asked the guy in the hardware store when I went in to get some matches. “Because then you are out of luck: Sold out since yesterday morning.”

Closed Businesses, Dwindling Income

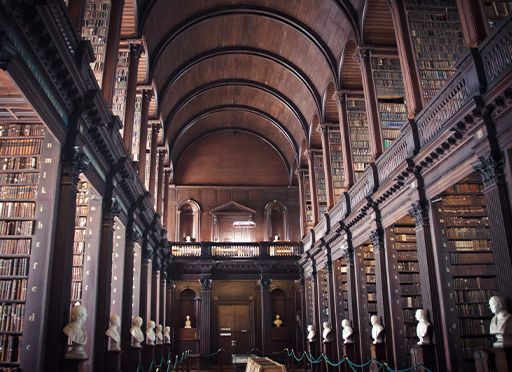

Still, for many, the weight of the crisis is becoming difficult to bear. Nine days ago – several days before any quarantine measures or school closures were in effect in our region – our older daughter and I went to visit a local hand-weaving workshop in Perugia, our regional capital and a true medieval gem. The manager of the cooperative, Giuditta Brozzetti, is an impressive, bustling craftswoman who has kept her family’s tradition of hand-weaving on antique Jacquard frames alive against all odds, one of the last in Italy to do so. The workshop is located in an ancient Franciscan church dating back to 1252, with high, luminous windows that were put in the 19th century when the building was first used as a place for textile manufacturing. In short: It’s any foreign tourist’s dream of traditional Italian craftsmanship combined with modern, effortless chic come true. Yet Brozzetti is currently very fearful about her workshop’s future: The business is marginal in the best of times. It relies entirely on tourist groups that relish her style and pay for the high-quality, hand-woven fabrics she produces with two other cooperative members. The day we visited her, we served as extras for a TV piece that was shot for local TV.

In the afternoon, a group of tourists that was rerouted from Venice that day – declared a red zone long before the rest of Italy – were scheduled to show up. But after that: Zero.

All bookings have been canceled until further notice. “If this goes on for much longer, I’m afraid I’ll have to give up,” she said.

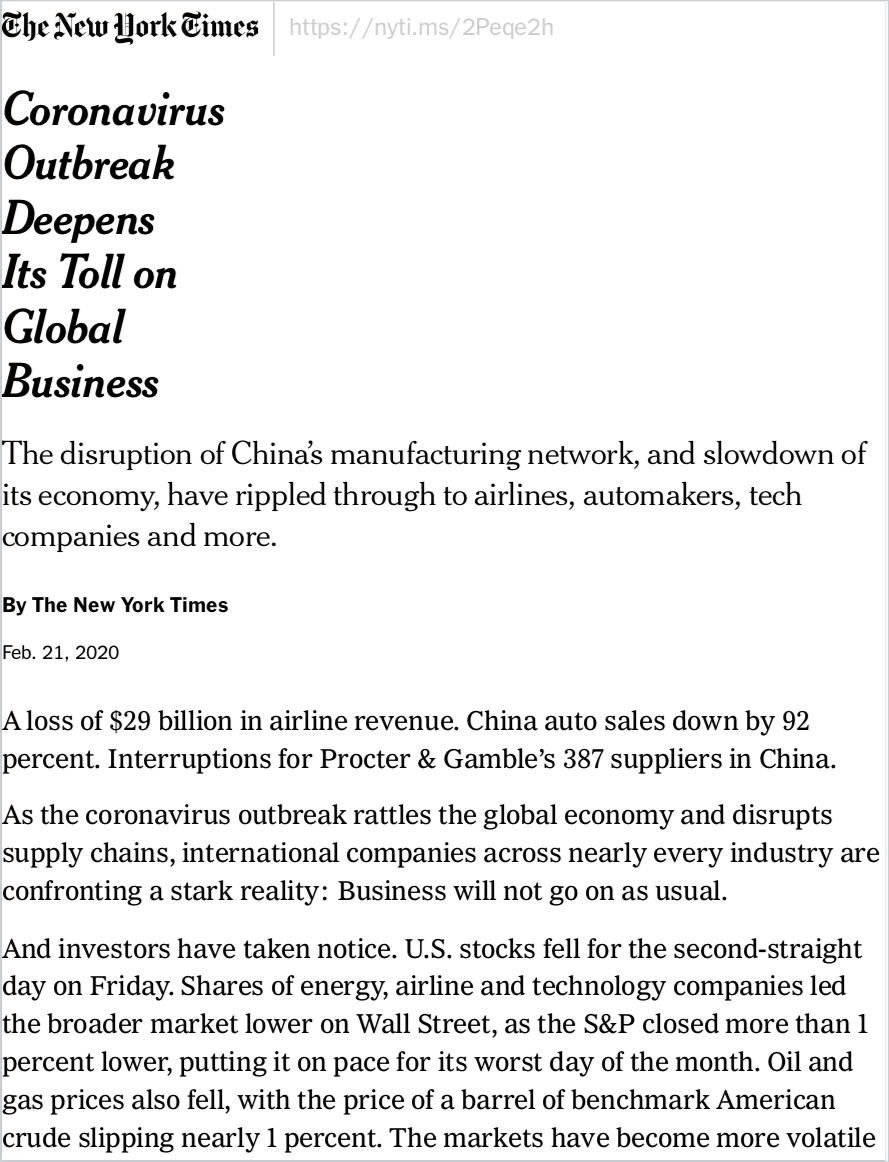

She isn’t alone. Tourism has been the only bright spot in an otherwise shrinking and stagnating economy over the past decade. It accounts for over 13% of the economy and was projected to rise steadily over the next few years. Now thousands of small and middle-sized enterprises – the backbone of Italy’s economy – are facing ruin.

This has even given rise to some acrid comments on the “I’m staying home” movement that’s sweeping through social media: “Lucky you, if you stay home on a state salary or on company leave. But how about us self-employed suckers?” The Italian government has already declared several emergency measures, aiming to help private mortgage holders or businesses in distress. Yet many people I know shrug this off, not least because they don’t trust their elected officials, who also gave many bold promises after the disastrous 2016 earthquakes – precious few of which, according to popular wisdom, have been kept.

Left Alone

Moreover, many Italians feel that they’ve been left alone in this. Contrary to the virus itself, the hashtag #let’s stop this together doesn’t transcend borders. In stark contrast to the 2008/2009 financial crisis, which saw some kind of coordinated action and public announcements to stem “contagion” early on, this time there has been deafening silence. Every country seems to be improvising alone, more concerned with a futile effort to keep out contagion than turn the tide on the virus. Already, France and Germany seem to be following the Italian pattern of infections with a delay of 8 to 10 days (on March 1st, Italy had 1337 cases). It may be better to follow Italy’s lead now, rather than wait for the numbers to climb ever higher.

“There are four stages of epidemic grief: denial, panic, fear, and if all goes well, rational response“, wrote Karl Taro Greenfeld in The Atlantic on March 5th. He was the editor of Time Asia living in Hong Kong during the height of the SARS outbreak between 2002 and 2003, which saw about 8,000 infected and 800 killed at the time. As of today, 12,462 have been diagnosed with the COVID-19 virus in Italy alone, and over 800 have died. Quite possibly, I myself was in a state of denial until just a few weeks ago, comparing this new disease to the common flu, pointing to all the other daily risks in life that we seem to accept and do nothing about.

By the Classic Playbook

Albert Camus wrote in The Plague: “A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure. Therefore, we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogey of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away.” Failing that, we scapegoat the most convenient bogeyman there is. The effects of rumors, fake news and mob mentality on the public psyche have also been in evidence here. Early on, people started to boycott Chinese restaurants and shops, suspiciously eyeing everyone that seemed to be of Asian descent.

Then, more recently, a post appeared on our village WhatsApp group announcing in all caps: “THE PATIENT ZERO WAS GERMAN – and GERMANY has hushed it all up, in a conspiracy to plunder the Italian people.”

Finally, when people were rushing to the trains to get out of Milan just before 16 million in northern Italy went under lockdown this past weekend, people in more modestly affected areas were lamenting the refugees’ egocentric behavior and lack of concern for their largely corona-free brothers and sisters in central and southern Italy.

Some of the most harrowing and moving accounts of societal breakdown in times of pestilence were written in this country: In The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio described the 1348 bubonic plague in Florence; how husbands left wives and parents fled their children, locals blamed foreigners and burned witches, and institutions dissolved. Another is The Betrothed, Alessandro Manzoni’s fictional rendering of the 1630 plague in Lombardy, which killed about two-thirds of the population at the time. The most haunting scene is the true story of a makeshift field hospital outside the walls of Milan with 16,000 suffering from the plague, where a herd of goats carefully moves between a teeming crowd of orphaned infants and toddlers, offering them their teats to suckle on. Truly, a last lifeline for kids abandoned in the plague. It is the story’s turning point: The young hero finds his betrothed, who has recovered from the disease, and life begins anew.

Habits Will Have to Change

A few months into this crisis, what we know for sure is that we still know too little about the coronavirus. Panicking, whether hoarding toilet paper in Australia, rushing trains in Lombardy or rioting in prisons, will not make the situation better. Until the scientists can catch up and offer clear answers about treatment, cures, vaccines and how to prepare for the next pandemic, patience and kindness are our best tools.

Self-isolation and distancing – staying a meter apart whenever in public – are not the same as alienation and egoism.

Habits will have to change, whether shaking hands or breaking bread, but just as students and teachers are rapidly adopting telelearning, we have to adjust to building and supporting our communities to build resilience in the face of such stresses. After a decade of finger pointing and weaponizing public discourse, our current crisis might offer us the best chance of learning how we can deal with global challenges without ripping ourselves apart.

For more information on the COVID-19 pandemic, please check out our related Coronavirus and Epidemics channels and subscribe to our getContext newsletter here.