Turn a Corner and There Is Hope

“Please shorten your shopping time! Do not crowd the supermarket!” The intercom repeated as I stood in the dairy section trying to decide between 20 brands of yogurt.

“Um. Argh. Okay, okay,” I muttered as I frantically picked one and moved on. Such is life in Beijing in times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Do not buy more than you need!” The intercom’s pre-recorded message continued to play on loop. “There is no shortage of food.”

My husband and I work in Beijing. Each year, we would leave the city a few days prior to the start of China’s week-long Lunar New Year holiday to spend the vacation with our family in California. We leave early mostly to avoid the rush of what’s known in Chinese as Chunyun, the world’s largest annual human migration, during which about three billion trips take place in the span of 40 days as Chinese people head home to celebrate the Lunar New Year with their families.

We embarked on our annual trip this year on January 17, a full week before the holiday. At the time, the novel coronavirus spreading in Wuhan was still an abstraction for Beijingers. The climate was one of concern, not fear. People pondered if the virus would affect their vacations. Wuhan natives living in Beijing were generally unfazed and still planned to return home for the holidays.

A lot of people, like us, were already on the move. Peak travel season in the world’s most populated country – the coronavirus could not have come at a worse time.

Less than a week later the Chinese government would impose a complete lockdown of Wuhan city, followed by nationwide school closures and orders for nonessential businesses to extend vacation or work-from-home indefinitely.

Beijing: A Ghost Town

When we returned to Beijing in mid-February during the height of the epidemic in China, the city was a ghost town. The line for foreigners at customs and immigration was empty. Airport staff asked us where we were transferring to and raised their eyebrows when we said this was our final destination. Upon arriving home, we were issued entry-exit cards for our residential area, limited to two cards per household. The next day, a representative from our neighborhood committee knocked on our door to confirm our arrival date and go over social distancing rules. Everyone was being asked to shelter-in-place, he said. The apartment building was disinfected daily. Supermarkets were open, delivery services were operating, and a limited number of restaurants were offering takeout. Pretty much everything else was closed. Makeshift walls were put up around our residential area, leaving only two entrances, where gatekeepers were stationed to check entry cards and take temperatures.

This was weeks into the crisis, so the initial phase of panic had already passed. Instead, the nation seemed to be breathing as one. Together we would wake up and immediately check the news for an update on the number of cases. We would clench our fists and curse at stories of selfishness, corruption and disregard for human life. We would cry over the accounts of doctors and nurses working day and night on the front lines risking their own lives. We would sigh over patients’ heart-wrenching stories of reunions and goodbyes.

We stayed home and dealt with our anxiety and cabin fever by live streaming, video chatting, working on home DIY projects, and attempting to conquer the kitchen.

And though, inevitably, there were conflicts that arose out of frustrations, most people did their best to cooperate with the gatekeepers when they went out. Gatherings of three people or more were strongly discouraged. Just about everyone wore a face mask – you’re likely to get a death stare from passersby if you don’t. As Connie Wang wrote in a Refinery29 article, the mask is “a symbol of reassurance and communal trust” and is the person “acknowledging that they are aware of their civic duty regarding public health.”

Mixed Feelings Toward the Chinese Government

This cohesive “breathe in, breathe out – we’re in this together” attitude was calming and inspiring. As the number of new COVID-19 cases began to decline each day, we were excited that these drastic preventative measures were, in fact, working! We also felt encouraged that our self-control was effectively contributing to the cause. At this point, many people began to struggle with their mixed feelings toward the Chinese government. In early February, anger and frustration over the government’s cover-up of the virus had reached a boiling point.

Coronavirus Timeline Leading Up to Wuhan’s Lockdown Shows Clear Signs of Cover-Up

YiCai GlobalCalls for accountability, transparency and freedom of speech on Chinese social media overwhelmed China’s internet censors.

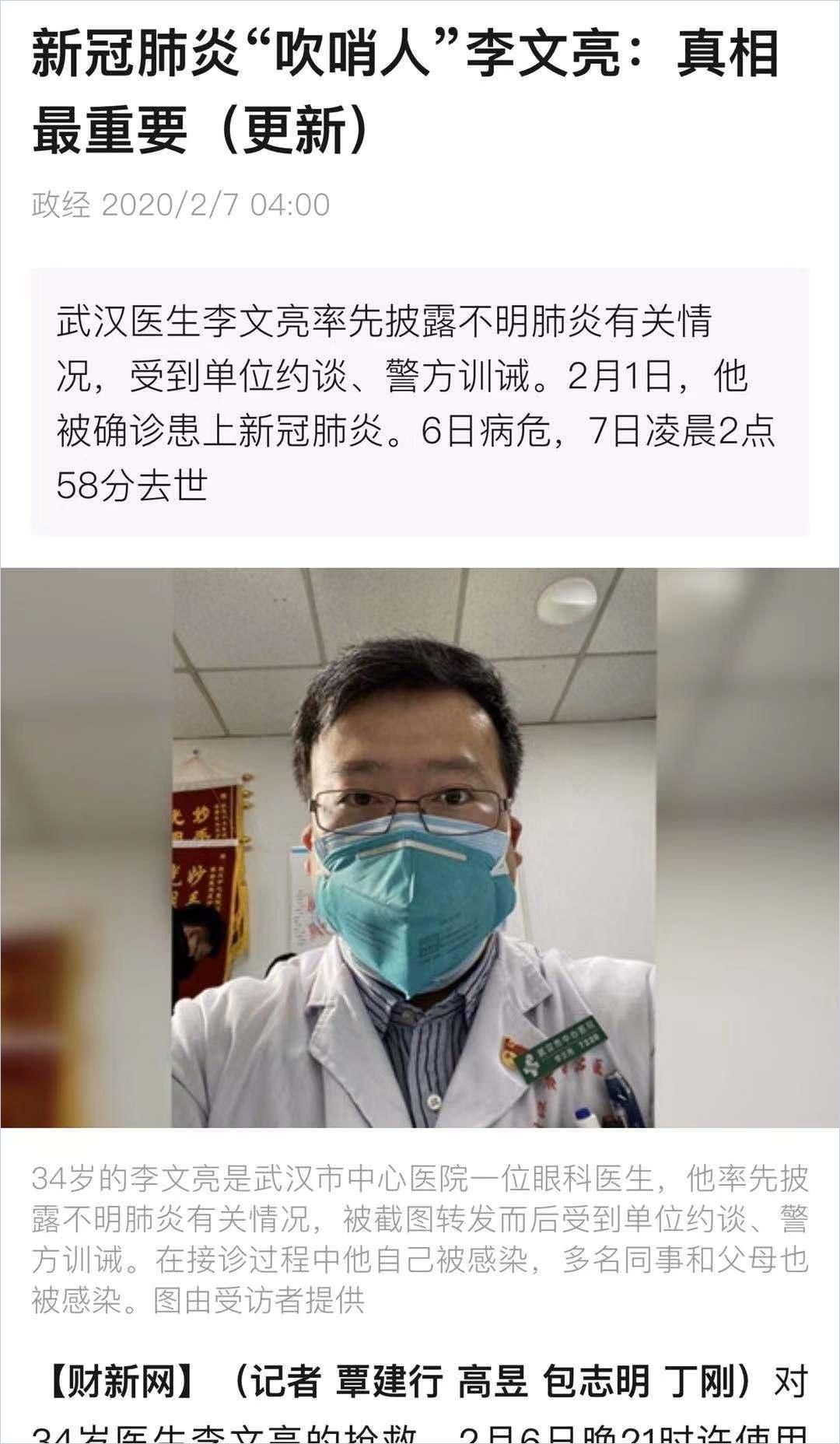

Coronavirus Whistleblower Dr. Li Wenliang Wanted Transparency More Than Justice for Himself

CaixinBut now that the government’s swift, bold, aggressive lockdowns have effectively controlled the spread of the virus, citizens are feeling a sense of pride for the government – especially knowing that such extreme measures are likely impossible to implement elsewhere in the world. People shake their heads at the irony as they try to reconcile this coexistence of pride and anger.

Overreliance on Technology

Chinese urbanites have very much been spoiled by the conveniences brought to us by the combination of cheap labor and advanced mobile internet services. The complaint is silly and trivial, but for many Beijingers one of the biggest disruptions brought on by the novel coronavirus has been being stripped of these conveniences. Many young people, for example, had never cooked before the pandemic. With affordable delivery services and nearly all restaurants offering takeout, urbanites routinely order food once or twice a day. We habitually order coffee, groceries and medicine to be delivered to our home or office. To send mail or packages, all you have to do is fill out a mailing form on your smartphone and a courier comes to you within an hour to pick up whatever you’re sending. Now, delivery can only get as far as the gated checkpoint of your residential area. A tent has been set up at the gate where couriers can leave your food and packages for you to pick up.

Through all this, people have been surprisingly good about not stealing other people’s stuff.

One positive that has come out of this challenging time is that we – a generation that barely knows how to feed ourselves without the apps on our phone – have actually become more hands-on with life. We’re going to physical supermarkets even when there’s a delivery option, because the supermarket really isn’t that much further than the gate and offers much more produce. As cabin fever sets in, trips to the supermarket have become a much-needed breath of fresh air. Young people are starting cooking challenges and competitions online, posting their successes and failures on social media as a form of entertainment.

China’s overreliance on technology has had one particularly notable plus side during this pandemic. The country is well on its way to a cashless society with 577.4 million people using mobile payments. In China’s largest cities, WeChat Wallet and Alipay have become the main means of payment for daily purchases. To prevent the exchange of germy cash that would aid the spread of the novel coronavirus, stores in China have put up signs asking all customers to use mobile payment methods.

Back to Normal?

Things here are now slowly getting back to normal. In fact, as I’m writing this blog article, a notification just appeared on my phone that the number of domestic cases of COVID-19 reported today has dropped to zero for the very first time! With the world still engulfed by the pandemic and the future unknown, it’s much too early to celebrate. Even as restrictions are eased, everyone is still acting with an abundance of caution. Every store, restaurant and office building continues to take logs of your name, temperature and contact information in case of infection. Now that more people are going out, restaurants are asking customers to sit diagonally from each other instead of face-to-face, and are providing serving chopsticks for each dish so that personal utensils are not dipped into communal dishes.

For my husband and I, while the immediate threat of the virus has seemingly subsided, anxiety has not. We fear for our friends and family outside of China. We’re afraid of what a global economic recession will mean for our future. And as Chinese Americans we’re frustrated by the xenophobia that is spreading more rapidly than the virus.

And yet, over the past month, I’ve video-called and reconnected with more friends than I have in years. I’ve also learned to take better care of my loved ones, my home and myself. As with any crisis, you turn a corner and there is hope. And it is my hope that we will come out of this – however long it takes – with something learned, something appreciated, something remembered.