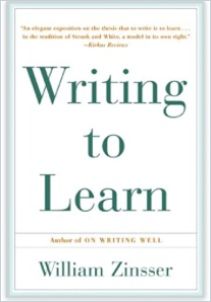

Writer, editor and teacher William Zinsser’s passion for clear writing fuels this inspirational treatise filled with elegant examples of beautiful writing.

Write Well, Think Better

Writer, editor and teacher William Zinsser, author of the classic On Writing Well, illuminates the connections between writing and learning. He provides broadly applicable lessons on how to improve your writing, using examples of great writing from more than a dozen thinkers from a wide range of disciplines.

Kirkus Reviews called this, “An elegant exposition of the thesis that to write is to learn…in the tradition of Strunk and White, a model in its own right.”

Fear of Writing

Zinsser opens by citing what he regards as two fears that bond millions of people. The first, he says, is a fear of unknown disciplines. The second fear, he writes, unites people across disciplines: a fear of writing.

We all need models, whatever art or craft we’re trying to learn.William Zinsser

Zinsser proves reductive as to the source of this fear. He contends that English teachers have to teach writing, but they love literature and an elevated bookish writing style, which students neither need nor want. Zinsser blames this tendency for students’ lack of motivation. He is not entirely convincing.

Writing organizes and clarifies our thoughts. Writing is how we think our way into a subject and make it our own.William Zinsser

But Zinsser hits the nail on the head when explaining that students would embrace learning to write if they understood that writing is difficult, and that any smooth, clear piece of writing likely has gone through a grueling editing process.

Zinsser describes the writing process as “linear and sequential” – the second sentence follows the first, the third follows the second, and so on. He posits that an author should provide readers with as much information as they need to understand what the writer wants to convey and nothing more.

Art

Zinsser discusses How to See, American designer George Nelson’s guide to decoding art’s complex codes. And he admires John Szarkowski, a curator in photography at the Museum of Modern Art, who shares the essence of photos and photographers to help viewers to understand them. Zinsser’s list of excellent art writers includes Paul Rand, a graphic designer, who shows readers how lines and fonts make up commercial design, and art historian E.H. Gombrich, who links art to the biology and psychology of vision. The best critics, Zinsser concludes, bring their passions to the page.

Again, Zinsser states the obvious to get his main points across. He notes that a good writer can bring any subject to vivid, engaging life. He enjoys zoologist Archie Carr, for example, on sea turtles in So Excellent a Fishe, which blends detailed, conceptualized understanding with image and metaphor.

Zinsser throws a bit of a curveball when he cites The Periodic Table, by Italian chemist Primo Levi, who enthusiastically discusses the names, qualities and categories of the various elements. Zinsser shows how, for example, Levi provides an unlikely, fascinating exposition on tin: Starting with his current scientific use of tin, he leaps back in time to the Phoenicians and how they traded it.

Think

Zinsser maintains that society desperately needs clear explanatory writing that communicates known information from one person to another. He ardently believes that lack of sound explanatory writing paralyzes society.

His suggestions are rudimentary but form a worthy program: Think through what you want to say. Write it out. Review it to see if you’ve conveyed what you set out to convey. Is your writing clear? Does it communicate the information needed? Zinsser states the obvious aloud – to any writer at least – when he explains that this kind of rigorous thinking about your writing always proves more difficult than the writing itself.

Zinsser crusades against noise – bad handwriting, poor page layout, weak typographics and cluttered sentences. He repeatedly urges you to omit from your writing all ambiguity, jargon, unneeded repetition and pomposity.

Information is your sacred product, and noise its pollutant. Guard the message with your life.William Zinsser

Zinsser cites George Orwell, author of Animal Farm and 1984, who felt modern writing had become abstract, wordy, distant and obscure. Zinsser stresses that to avoid these traps, you must write in active voice, with lively verbs and concrete, specific nouns.

Happily Off-Topic

Zinsser doesn’t exactly prove his supposed thesis about the links between writing and learning. Happily, he goes slightly off-topic to remind readers how to write and to provide outstanding examples of writers in arcane fields – as cited above – whose wordsmithery enables laypeople to learn and understand. Zinsser reverts to describing – with great clarity, purpose and understanding – how you should write, how you should never write, how you should think about what you have written, and how you should improve it. In this handbook, as in his renowned On Writing Well, Zinsser produces a canonical work, one that will inspire and improve any writer, no matter how experienced. Zinsser’s heartfelt passion for the written word would be inspiration sufficient, but coupling that passion with accessible worthy examples makes this an invaluable, fun and illuminating text.

William Zinsser’s books include, among others, Writing About Your Life, Inventing the Truth and The Writer Who Stayed. Otherwise helpful books on writing include Bird By Bird by Anne Lamott; The Elements of Style by William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White; and Writing Tools by Roy Peter Clark.