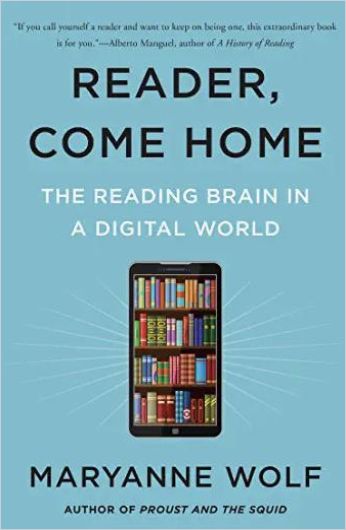

Maryanne Wolf, author of Proust and the Squid, discusses the mental, psychological and spiritual benefits of reading.

Read!

Maryanne Wolf, Director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, urges you to respect the time and space of deep reading in a world of technological distractions. She explains complex research in neuroscience and psychology that reveals how engaging with technology alters your ability to read. She says children today are the unwitting subjects of a massive social experiment in technological proliferation.

While Wolf raises numerous issues, she also proposes solutions. Her work articulating technology’s neurological and intellectual impact is profound, and proves relevant for parents and educators.

The Washington Post said that Wolf, “offers a persuasive catalog of the cognitive and social good created by deep reading.” And The San Francisco Chronicle said, “Wolf is a lovely prose writer who draws not only on research but also on a broad range of literary references, historical examples and personal anecdotes. [She]… makes a strong case for what we lose when we lose reading.”

Reading

Speaking is natural, Wolf explains, but reading requires an education that enables the creation of neural circuits that process language and vision. To produce the act of reading, the author explains, the brain must create vast neural connections.

Wolf cites a worrisome Stanford study finding that young people today are exhibiting a 40% reduction in empathy. She attributes this decline to their overdose of media stimulation. Today’s glut of information, Wolf maintains, makes people less likely to examine what they receive, compare it to other situations and remember it for future situations.

Words contain and momentarily activate whole repositories of associated meaning, memories and feelings, even when the exact meaning in a given context is specified.Maryanne Wolf

In comparison, Wolf discusses how deep reading allows people to capture other people’s feelings. She details how it cultivates the analytic skills of observing and drawing hypotheses and predictions based on inference and deduction, testing and evaluation, interpretation and conclusion.

Wolf asserts that reading requires a kind of attention that electronic communication does not. Media produces both stimulation and a disposition toward boredom that encourages switching tasks, which leads to hyperattention. Wolf reveals that reading on screens leads people to scan for words, imagine the context and leap to conclusions. Increasingly, she cautions, people come to process all information as if it were entertainment. She bemoans the loss of complex thought articulated in precise language and finds that people become less likely to identify subtle distinctions in society and group dynamics.

Children

Wolf emphasizes that young minds need to learn to focus. Electronic media put kids in a state of stress because cortisol and adrenaline must flush their brains to manage the constant influx of stimulation. Children thus develop an addiction to dopamine, the hormonal reward of rapid shifts in attention. This search for constant external stimulation, Wolf unpacks, leads to multitasking, boredom and an inability to sustain effort.

She relates that many adolescents spend more than 12 hours a day on screens, and researchers do not yet understand what neurological impact that is having. Wolf reminds you that the stimulating environment of digital media makes it difficult for children to settle into a reflective mind-set.

Wolf explains surprisingly that adults typically can’t listen to a news report and simultaneously read the text scrolling beneath it. Yet, such stimulation bombards children, so, she concludes, their working memories may be shrinking. Wolf warns that researchers don’t know yet understand how this might change children at later developmental stages.

Children, Wolf insists, should become aware that reading takes time and attention. She cites evidence suggesting that parents have been tending to read less to children since 2008. E-books seem to change the reading dynamic; adults don’t address content the way that they do when reading a physical book. And, Wolf shows, children whose parents don’t read to them score worse on literacy measures than children whose parents do.

“Hinge Moment”

Wolf explains that investor Warren Buffett leaves blocks of time with no scheduled activity in his calendar because he views time for reflection as precious. The author argues that time fuels the critical analysis necessary to transform information into knowledge that your memory will hold. She refers to this as a hinge moment because interactions, perceptions, understanding and decision-making all change during it.

Deep reading is both a real, flesh-and-cranial-bone reality and a metaphor for the continuous expansion of human intelligence and virtue.Maryanne Wolf

Wolf returns to her theme to restate that advances in technology should never come at the cost of analysis and reflection.

Reading

Wolf offers a call to action that can be summed up in one word: read! Unlike many authors who lament the likely impacts of social media and media bombardment in general on literacy, intelligence and human bonding, Wolf offers ample studies and citations from experts to back up her conclusions. Her impassioned exhortations in favor of the printed page are likely to resonate deeply with those already vested in such reading.

Whether she can – as she clearly wishes – bring screen addicts to printed works is another question. Wolf may be preaching to the choir, but she obviously hopes to convert people to the cause of reading from a real page – at the very least, parents who read insufficiently to their children. Wolf’s own writing is lively and accessible, and the depth of her arguments seem irrefutable. So, take a half an hour today, and open a book. Your brain will be glad you did.

Worthy ancillary works on reading and the brain include Wolf’s Proust and the Squid; Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene; and Language at the Speed of Sight by Mark Seidenberg.