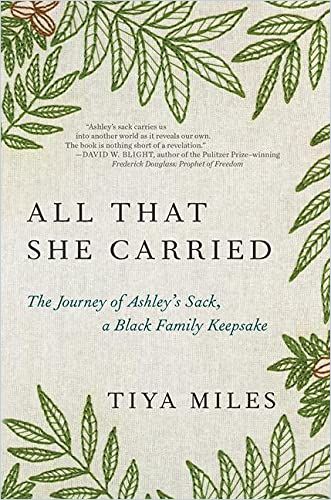

US National Book Award winner Tiya Miles relates the heartbreaking saga of a young enslaved girl being separated from her mother and sold in pre-Civil War America.

Identity in a Small Sack

The auction block meant terror for enslaved people in the United States before the Civil War. In this lyrical US National Book Award winner, Tiya Miles – MacArthur Foundation fellow, Harvard professor and author of The Dawn of Detroit – describes how one enslaved mother packed a survival bag for her preteen daughter before an auction severed their connection forever.

A Survival Bag

South Carolina plantation owner Robert Martin died in the mid-1800s. Rose, an enslaved woman, feared Martin’s family would sell the plantation’s so-called “human assets,” including Ashley, Rose’s nine-year-old daughter.

Brokers and plantation owners sold children for profit. Enslaved female children and teens faced the risk of rape, sexual assault and exploitation. Some would-be buyers lobbied to “sample” the human merchandise before they bought.

When the auction block loomed on her little family’s horizon, Rose gathered all of her resources – material, emotional and spiritual – and packed an emergency kit for the future. Tiya Miles

Rose’s fears were realized when Martin’s heirs sold Ashley to another plantation owner.Facing her daughter’s imminent departure, Rose packed a small emergency bag of supplies to sustain her daughter on emotional, mystical and physical levels. Rose never saw Ashley again.

Three generations later, Ruth Middleton – Rose’s great-granddaughter, Ashley’s grandchild – held the same cloth sack Rose had given Ashley.

Ruth Middleton

In 1921, Ruth Middleton took up needle and thread to record the pre-Civil War history of Ashley’s cotton sack. Ashley’s bag, now decorated with the narrative Ruth embroidered, highlights the life and motherly love of three Black women: Rose, the enslaved matriarch; her enslaved daughter Ashley; and Ruth Middleton, Ashley’s granddaughter. The fourth woman in that generational saga, Middleton’s mother Rosa, died young, and therefore plays only a minor role in the history of Ashley’s bag.

The bag has historical significance to scholars, but its meaning was deep and personal to Ashley after her forced separation from her mother.

Decades later, Ashley shared her story with Middleton.

Historians have had difficulty gathering simple facts or concrete proof to document Rose’s existence. Basic details – her last name, birthdate, birthplace and the day of her death – vanished into the historical void of enslavement. In contrast, copious records detail the life, property and homes of Robert Martin and other plantation owners who bought and sold enslaved people.

The emotional shelter of love eternal would travel with Ashley inside the sack.Tiya Miles

Plantation records yield few clues about Rose, including her name. “Rose” was a common name for enslaved women, as can be seen in the surviving “blanket books,” which are records that list the names of slaves who received bedding or fabric from plantation owners. The name Rose appears frequently in blanket books preserved in South Carolina and other Southern states.

Traveling Bag

In mid-December of 1852, a physician diagnosed plantation owner Martin with a fatal case of “brain disease.” The enslaved people on his plantation began worrying about possible liquidation sales that would split up their “unfree” families

After a sale, enslaved people often traveled from their last home to their next one carrying a small bag of possessions and keepsakes. Speculation about Martin’s health and impending death prompted Rose to prepare such a sack for her daughter.

Rose collected and packed items that would sustain Ashley on physical, emotional and mystical levels. Records suggest Rose worked in the kitchen of the Martin home. With access to its supplies, it seems she would have been able to prepare an empty flour bag or “cotton seed sack” to serve as Ashley’s traveling bag.

The bag demonstrates Rose’s creativity, dedication and resourcefulness. You can envision her searching the plantation kitchen or storage room to find a suitable container to serve as an emotional “parachute” for her child.

In her embroidered inscription, Middleton provides an inventory of the items Rose put in the sack. The bag contained one worn dress, three handfuls of pecans and a single braid of Rose’s hair.

Ashley later told her granddaughter Ruth that the bag also contained eternal love. The act of packing the bag and the items in it nourished Ashley during her relocation, and nurtured her descendants with evidence of enduring motherly care, affection and protection.

By packing a dress – even a worn or tattered garment – Rose asserted Ashley’s claim to dignity, femininity and “bodily protection.”

When Rose added pecans to Ashley’s bag, she packed a practical protein snack for her young daughter. Pecans rank high as a long-lasting survival food. In this case, they represented two layers of hope and sustenance. As a snack, the nuts provided Ashley with nutrition during her journey. And as potential seeds, the nuts promised future growth and sustainability.

Family Memoir

During the 1920s – only two generations after the end of slavery – Middleton embroidered a family memoir about maternal love on the outer fabric of Ashley’s bag. Its inscription reads: “She never saw her again.”

Ashley survived the Civil War and its violent aftermath, when African-Americans faced deprivation and terror. She would have been about 20 years old when the war ended. After the war, armed, violent groups of white men terrorized Black families.

Following the upheaval of war, freedom for African-Americans was ‘fragile,’ an uncertain condition of new ‘privileges’ bound with ‘terrible disappointments.Tiya Miles

Legislators in South Carolina and Virginia enacted racially oppressive “Black Codes.” These laws limited African-Americans’ activities, employment, civil rights and voting rights. Those who committed misdemeanors or other infractions could be sentenced to forced labor.

In 1918, Ruth and her husband Arthur migrated to Philadelphia to escape the racial dangers Black Americans faced in the South. Ruth carried Ashley’s cotton sack.

Emotional resonance

Tiya Miles is a skilled and moving writer. She distills history to its core of emotional resonance. Here she connects disparate facts to create a clear portrait of the cruelty of slavery and the depth of familial love. That love, Miles makes clear, was the only protection against the physical, emotional and spiritual brutality of enslavement. Her book is necessary today as a document of what enslaved people suffered before and after the abolishment of the practice in the United States. Yet this is not an entirely grim tale. Miles’s depiction of Rose’s family’s devotion – including the legacy of love family members continued after Rose’ death – is inspiring. Miles’s heartbreaking account will resonate with anyone seeking the truth about the horrors of enslavement.