To make sure your students retain their lessons, engage their brains’ memory systems!

How Students Learn

“Fire Together, Wire Together”

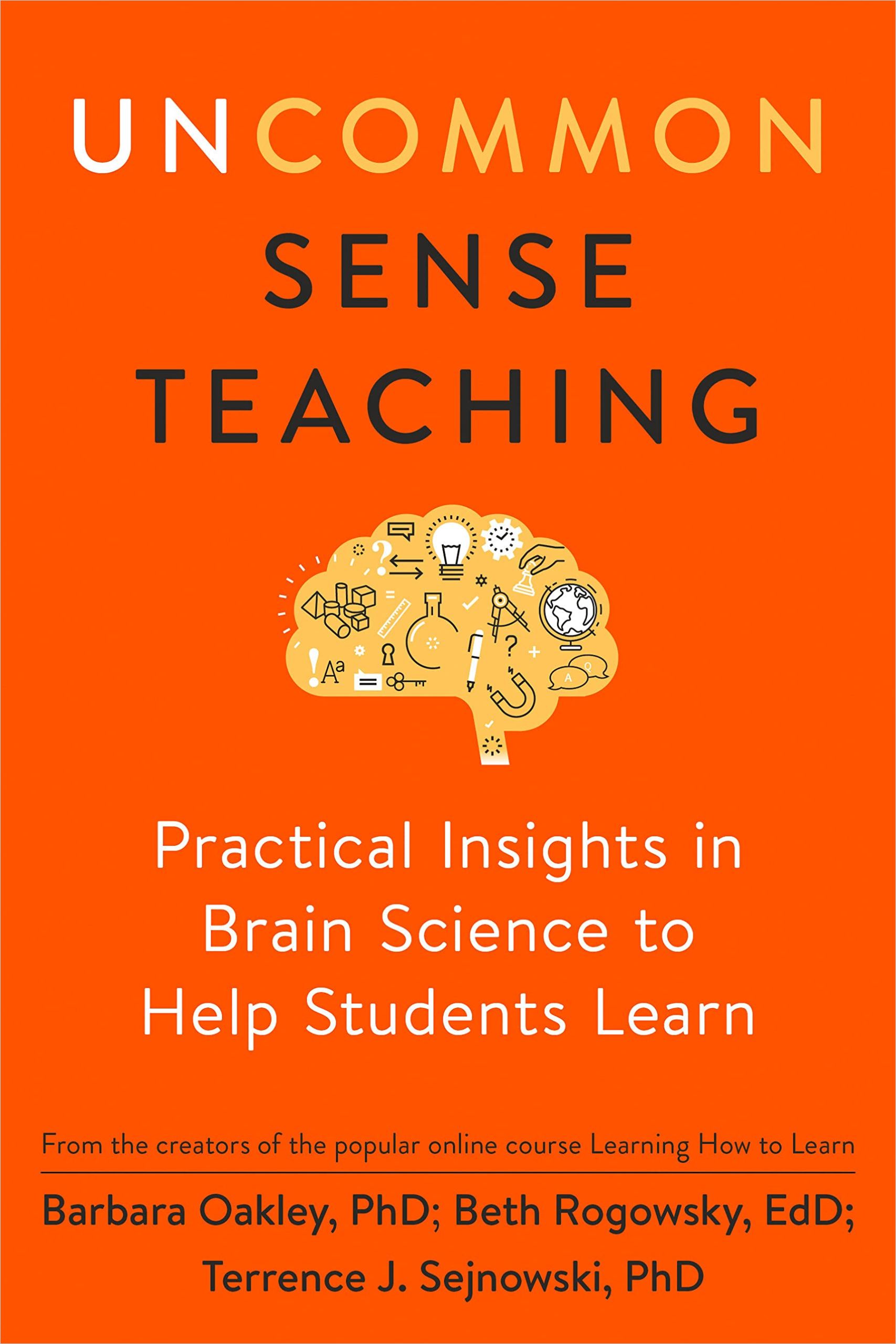

In this practical teaching guide, professors Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky and Terrence J. Sejnowski share their knowledge of educational methods and the neuroscience of learning. They help teachers understand how their students’ brains work and show them how to meet individual student’s needs.

Barbara Oakley, PhD teaches bioengineering and neuroscience at Michigan’s Oakland University. Beth Rogowsky, EdD teaches education at the Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, and Terrence J. Sejnowski, PhD teaches computational neurobiology at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

As students are learning, neurons are linking and strengthening…this process [is] ‘learn it, link it’.Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky and Terrence J. Sejnowski

The authors explain that learning requires establishing, fortifying and expanding neural pathways in the neocortex’s long-term memory through a process they call, “learn it, link it.”

The brain uses different memory systems. Working memory holds a few separate clusters of information so briefly that they may disappear within seconds. Long-term memory’s neural pathways can manage and extend the capabilities of working memory. Learning requires connecting working memory with long-term memory, which retains content over the long run, potentially for life.

Working memory capability varies among students, so teachers must diversify their methods to make sure each person can learn – without overwhelming or underwhelming individual learners. To avoid overburdening students’ working memories, the authors say, fragment information into smaller conceptual units and activities.

Active Learning

Students engage in active learning during class activities and discussions, both of which can accelerate the process of channeling information. To help their students’ brains fortify new neural links, teachers can intersperse their presentation of new information with exercises and short (60 seconds or fewer) “brain breaks.” With practice, the neural links going from working memory to long-term memory get stronger and retrieval becomes faster.

Teachers can use the spaced repetition of important knowledge to help students transfer it from working memory to long-term memory. Collaborative exercises, such as group discussions, can help students process the material they are learning. Retrieval techniques, like quizzes, benefit long-term memory.

When you just think about something you don’t like or don’t want to do, it can cause feelings of pain that encourage you to think about something different. The result is procrastination.Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky and Terrence J. Sejnowski

Students often procrastinate when they are facing demanding assignments. Teachers should encourage them to work until they encounter frustration and then to take a break to switch between modes. This can alleviate students’ anxiety as they learn complex subjects. Teachers can also help students overcome procrastination by encouraging them to be more accountable, establish to-do lists and tidy up the area where they study.

Learning flourishes when students pair rigorous mental effort with cognitive downtime, including sufficient sleep. However, when students face tasks they dislike or are hesitant to undertake, they feel uncomfortable and tend to think about something else. That also leads them to procrastinate.The authors warn, however, that cramming the night before an exam does a poor job of building neural links.

Two Pathways

The declarative learning pathway consciously facilitates knowledge acquisition, while the procedural learning pathway operates unconsciously.

Teachers can guide students in acquiring information through both systems to help them become flexible, swift and adaptable problem solvers. First, enhance your students’ declarative learning by starting with explanations and demonstrations. Then, follow up with practice sessions to activate their brains’ procedural pathways.

Be aware that explaining a concept to students doesn’t guarantee that they will develop a deep understanding of it.The authors advise that students must apply a concept – not just verbalize it – to understand it fully.

Fundamentals

Productive learning and studying behavior can become second nature to your students, with your help. Make sure they arrive on time for class with the necessary materials and always complete their assignments. Describe what you want your students to learn. Create a detailed lesson plan with clear goals, expected outcomes and questions students should be able to answer after they complete studying the relevant material.

As you begin, describe the tests or other assessments, materials and resources the students will work with, and outline the rules of educational engagement, including strict start times and homework expectations.Schedule individual meetings with students to build relationships with them and discover their unique qualities.

Connect the lessons you’re teaching to concepts that might be of extra interest to your students, such as real-life problems, case studies and experiments. Cover challenging material first, lecture-style. Build on students’ prior knowledge, ask questions and offer demonstrations. Teach difficult ideas in chunks that build on each other. Encourage students to take notes and even illustrate the material.

At its simplest, neurons link, are strengthened with practice and…extended with new and diverse learning experiences.Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky and Terrence J. Sejnowski

Chronic stress can damage students’ health. To avoid it, encourage moderate, short-lived stress, which triggers the release of glucocorticoids and other biochemical agents that enhance their learning capacity, cognition, working memory and physical strength.

Design group learning tasks to encourage practice, positive interdependence, individual responsibility and social skills. Establish standards for collaborative work, including behavioral expectations and strategies to deter loafing on teams.

Linking brain science to learning

Professors Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski link neuroscience to teaching principles and explain how the brain learns. This dual mission could disappoint readers who seek a deeper dive into neuroscience. And, the basic teaching responsibilities the authors outline will not be new to most teachers, though Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski do provide a systematic approach that less experienced teachers will welcome.

The book is written in a dry, academic tone that may hinder readers’ retention of its lessons, but the authors’ passion for teaching – and for teaching teachers how to understand their students’ learning processes, often a frustrating mystery – overcomes any flaws in their style or approach. By describing how information moves between working memory and long-term memory – along with techniques, hacks and motivators to improve this process – Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski provide teachers with valuable, applicable insights derived from solid research.