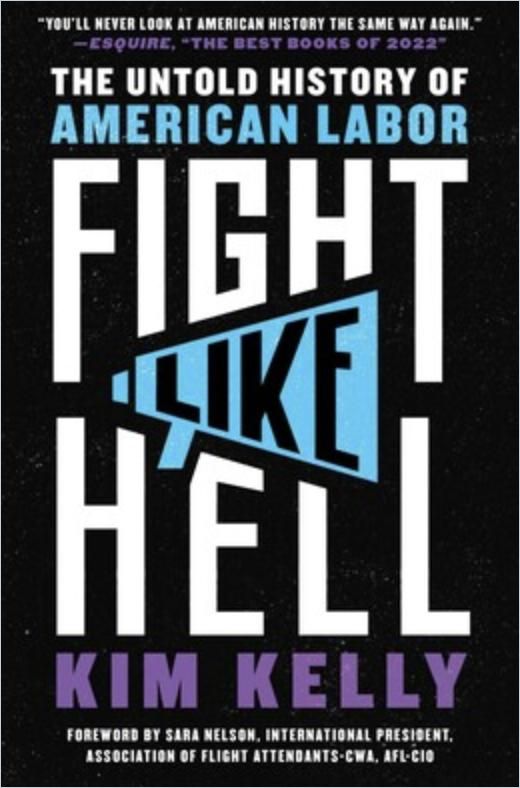

New Republic journalist Kim Kelly offers an impassioned history of the United States’ labor movements and the tactics owners used against workers.

To the Barricades!

Journalist Kim Kelly, who writes on labor, class, politics and culture, offers a history of United States labor movements, highlighting courageous workers and union leaders; the prominent role of women in labor organizing, and corporations’ often-violent anti-union tactics.

Kelly’s work appears in the New Republic, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Nation and Esquire. She is also a columnist for Teen Vogue.

America’s Industrial Revolution

During the Industrial Revolution in 19th-century America, formerly self-supporting farmers and craftspeople took jobs in factories, slaughterhouses, railroads and mines. Factory employees worked with unprotected dangerous machinery, losing fingers and limbs. Coal dust gave miners black lung disease, and cotton fibers gave textile mill laborers brown-lung disease. At a typical factory, like one in Rhode Island, children as young as seven toiled up to 16 hours daily for 40 to 60 cents per week.

Every labor story invariably builds on years – if not centuries – of previous organizing victories and failures.Kim Kelly

In the Victorian era, immigrant, Black and Indigenous women earned meager wages doing domestic labor. As the Industrial Revolution advanced, middle-class women began working at textile mills. They labored in 12-hour shifts in New England textile mills under terrible conditions.

Kelly traces the history of US labor protests, starting in 1824, when women carried out America’s first factory strike against eight Pawtucket, RI mills. Hundreds of male coworkers joined them. More than 20,000 New York garment workers went on strike in the 1909 “Revolt of the Girls.” In the 1912 “Bread and Roses Strike” in Lawrence, MA, 25,000 mill workers walked out.

Mill owners believed young female workers would quit when they got married and thus could never be part of a permanent labor class. They worked in stifling factories where bosses often nailed the windows shut and locked the doors to prevent theft. On March 25, 1911, 146 workers died in New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire; many were unable to escape because the factory’s doors were locked.

Minority and immigrant workers

After Emancipation, many Black women washed white families’ laundry by hand for low pay. In 1866, a pioneering group of Mississippi laundry workers organized as The Washerwomen of Jackson and petitioned the mayor for $1.50 for a day’s washing. Similarly, in 1881, Atlanta laundry workers founded the Washing Society to seek higher wages. The washerwomen won formal control over the city’s “hand-laundering industry.”

Whether held in bondage or living freely, Black women were expected to work from the moment they were old enough to hold a broom.Kim Kelly

In the late 19th century, mines hired immigrants from around the world – China, Japan, Mexico, Latin America, Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean – in hopes that workers of different nationalities would never join together in collective labor action. That hope was thwarted. For example, during an 1890 labor dispute, the Union Pacific Coal Company recruited Black workers to replace white ones. The Black workers refused to be strikebreakers and joined the strike.

In the early 20th century, the Women’s Trade Union League and the Domestic Workers Union of New York advocated for laundry and domestic workers. The National Domestic Workers Union (NDWU) grew to 13,000 members in 10 cities.

Labor activist Frances Perkins joined President Franklin Roosevelt’s cabinet and contributed to developing Social Security, the 1935 National Labor Relations Act and the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which instituted a minimum wage and banned child labor.

Intimidation and Violence

Kelly reports that corporate anti-labor and anti-strike actions often became violent. During the 1914 Colorado Coalfield War, mining company thugs and the state National Guard killed 21 striking miners. During a 1917 strike, the Phelps Dodge mining company shipped 1,200 union members in cattle cars nearly 200 miles from an Arizona copper mine and left them in the desert. During the Montana miners’ strike that year, armed men kidnaped labor organizer Frank Little, tied him to their car, dragged him out of town and hanged him.

Anti-labor actions may have become less violent, but not necessarily less drastic. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan crushed a Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike, firing thousands of air traffic controllers and banning them from the airline industry for life.

The Industrial Workers of the World

Before World War I, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or “Wobblies,” became the most prominent anti-capitalist union. Membership was open to everyone, except police, prison guards or landlords. IWW member Ben Fletcher, a Philadelphia dockworker, led the IWW’s Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union, Local 8. He encouraged members to support America’s World War I efforts, but the US government arrested him and other union members under the new Espionage Act. The government sentenced Fletcher to 10 years in federal prison and fined him $30,000. In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt pardoned Fletcher and other imprisoned Wobblies.

“Militant socialist” Mary Harris, far better known as Mother Jones, was one of the 19th century’s most effective labor organizers. She cultivated a grandmotherly image by wearing a black dress with a lace collar and pulling her white hair back into a bun, but she proved a fierce fighter for mill workers’ and miners’ rights. In 1903, to protest child labor, she led 100 workers on a three-week trek from Philadelphia to the New York home of President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1914, on her way to the Colorado Coalfield War strike, authorities arrested and imprisoned her, making her forever a feisty symbol of labor rights.

Anti-Union Conservative Dogma194

Reagan-era antipathy to union labor hardened into a central pillar of Republican ideology and policy in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Large strikes grew rare, dropping nearly 90% between 1977 and 2016. Republican-controlled “right-to-work” states raised almost insurmountable barriers to union organizing.

Kelly reports that a 2020 poll found that 65% of Americans approve of labor unions. Anger over inequality and injustice increased during the COVID pandemic. Millions lost their jobs or had to work under risky circumstances without labor protections.

[The pandemic] exposed the rotten, hazardous conditions that have been allowed to fester thanks to capitalist cruelty and federal malfeasance…by hitting the streets and raising the alarm, workers are now fighting back.Kim Kelly

In 2021, nationwide protests, walkouts and strikes increased. In a movement that came to be called the “Great Resignation,” millions abandoned poorly paid or high-risk jobs. In September 2021, 4.4 million Americans left their jobs. This mass movement may reveal new opportunities for renegotiating relationships between capital and labor.

“I’m Stickin’ With the Union”

Kim Kelly is a pro-union firebrand as well as an accurate, evocative historian. Her passion makes this an inspirational union history – for some. Those who do not sympathize with organized labor may not empathize with her manifesto of worker support, though they’ll have an eye-opening read. Kelly writes with a keen awareness of class divisions in America, something few writers note with insight. Her historical research delves into the struggles of immigrants, people of color, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ employees, sex workers and prisoners. Kelly firmly believes that labor must organize to fight corporate owners’ tactics, particularly when they become oppressive. As the real value of wages diminishes and the top 1% grows daily richer, readers may find much to learn and to like in Kelly’s chronicle of labor battles.