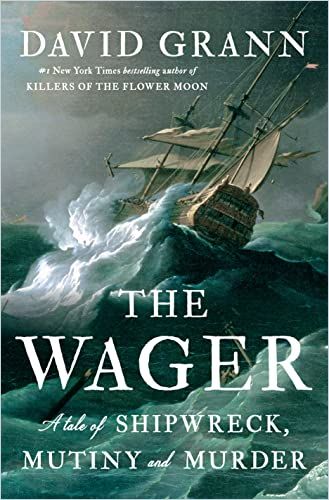

New Yorker staff writer David Grann — author of Killers of the Flower Moon — recounts the 1741 shipwreck, mutiny, depravation, and survival of the HMS Wager‘s crew.

Death at Sea

In this bestseller, New Yorker staff writer David Grann unveils the harrowing saga of the 1741 wreck of the HMS Wager. He is also the noted author of Killers of the Flower Moon, The Lost City of Z, The White Darkness, and the collection The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: Tales of Murder, Madness, and Obsession.

HMS Wager

In the 1740s, Spain and England competed to expand their global presence, establish colonies, and profit from the mineral and slave trades. Their battles took place mostly at sea.

Grann narrows the conflict to one warship. England’s HMS Wager set sail against Spain with 250 officers and crew aboard in 1740. It embarked in a squadron with the warships Pearl, Severn, Gloucester, and Centurion for a voyage around South America’s lethal Cape Horn. The squadron’s well-respected leader, Captain George Anson, had orders to loot Spain’s ships, and particularly to pursue and plunder its treasure ship which sailed from Mexico to the Phillippines.

We rummage through the raw images of our memories, selecting, burnishing, erasing. We emerge as the heroes of our stories, allowing us to live with what we have done – or haven’t done.

David Grann

British naval crews included civilians seized by press gangs — invalids, old men, and young boys. Before the squadron sailed, typhus killed dozens. Hundreds more fell ill or deserted. Just getting through the English Channel and out to sea took a month, including three launches and failed attempts.

The Wager’s crew included Captain Dandy Kidd, a beloved leader, and midshipman John Byron, 16, the aristocratic younger brother of Lord Byron. The Pearl’s captain soon resigned, citing illness. Anson named Kidd as captain of the Pearl and designated nobleman George Murray to lead the Wager.

Since the squadron had left England, 160 of its roughly 2,000 members had perished. And the fleet had not even begun the most perilous part of the journey.

David Grann

When Kidd died of fever, Anson promoted Murray to the Pearl and gave the inexperienced David Cheap command of the Wager. Grann captures how the ship and its crew met their misfortunes under his contentious watch.

Rounding Cape Horn, a gale drove the Wager out of the squadron’s formation. Ice-cold rain and violent winds pounded the ship. Many of the men were dying from scurvy; their teeth and hair fell out, and they suffered intolerable pain and madness. No one then knew scurvy’s cause or the benefits of eating citrus to prevent it. On the Centurion, 300 of the 500 crewmen died. Some 75% of the Gloucester’s sailors perished. The squadron lost 1,000 men.

The Wager survived the voyage around Cape Horn and proceeded up the Chilean coast. Gunner John Bulkeley, who thought Cheap reckless and autocratic, believed the ship could not survive, even to make it to the squadron’s rendezvous north along the coast.

On May 13, the Wager’s topsail gave way, rendering the ship defenseless against the winds and currents dragging it ashore. It grounded that night, fortunately wedging between two rocks instead of sinking immediately.

The 145 survivors salvaged what they could from their ship as it broke apart. Competition for food and rum turned violent. Hunger set in, the island offered little game, and the waters were too rough for fishing. And the inexperienced Cheap struggled to maintain order. Among ample examples of Cheap’s approach to his crew members, Grann captures the moment the Captain reminded them that disloyalty on land was akin to mutiny at sea and would be punished by death.

The native Kawésqar people kept the crew alive by spearing fish, setting snares, and providing shellfish and seaweed. Cheap’s unruliest men offended the Kawésqar by chasing their women, causing the tribe to depart. The men, who hadn’t learned how the Kawésqars collected food, fell back into starvation and chaos.

Factions

The crew split into factions: one loyal to Cheap and the other to gunner John Bulkeley. When a man was caught stealing food and rum, Cheap had him flogged nearly to death. When another sailor aggressively challenged Cheap’s authority, the Captain shot him in the face.

As Cheap lay secluded in his shelter, worrying – Grann reports in a glimpse of the Captain’s inner self – about having killed a crew member, a carpenter aligned with Bulkeley led the salvage and repair of one of the Wager‘s longboats. Bulkeley’s faction planned to sail through the Straits of Magellan, avoiding Cape Horn, and then to go to Brazil. Cheap intended to continue the Wager’s mission up the Chilean coast to the squadron’s rendezvous point.

On August 4, 1741, Bulkeley presented Cheap with written notice of his intention to sail to Brazil. His men offered Cheap a formal letter stating their mission. If he refused to sign it, they told him, they’d forcibly relieve him of command.

Cheap refused. Bulkeley and his men backed off, but over the next few weeks, starvation took many lives. Some men even resorted to cannibalism.

On October 9, Bulkeley’s men arrested Cheap and then, five days later, set sail in three boats, leaving Cheap and 20 loyalists on the island with meager rations and a small, half-destroyed boat.Byron elected to leave with Bulkeley. Not long after they departed, however, Bulkeley sent Byron back in a barge to retrieve necessary materials. Honor overcoming his fear of death, Byron defected to Cheap.

Brazil or Chile

After three months and 3,000 miles of sailing, Bulkeley’s men reached Brazil; only 29 men survived out of 81. From there, they returned to England.

Cheap, Byron, and the Wager’s remaining crew sailed up Chile’s Pacific coast in the repaired small boat and Byron’s barge. They lost the boat and most of their food. The miraculous appearance of native Patagonians, who guided them up the coast in dugouts, saved their lives.

In Chile, the Spanish imprisoned Cheap and his men. Two and a half years passed before they were permitted to return home.

Bulkeley and his men created a sensation when they reached London. To get his account on the record, he published a best-selling book. When Cheap unexpectedly returned months later, his accusation that Bulkeley had committed mutiny led to a court-martial.

Empires preserve their power with the stories they tell, but just as critical are the stories they don’t – the dark silences they impose, the pages they tear out.

David Grann

When Bulkeley entered the courtroom on April 15, 1746, he realized that the Navy wanted to avoid the bad publicity his prosecution would unleash. Accordingly, the court acquitted Bulkeley, Cheap, and all the surviving crew members.

Bulkeley emigrated to America, republished his book, and lived quietly. Byron fathered six children and rose to the rank of Vice Admiral. Cheap’s naval career flourished with the support of now Admiral Anson, who destroyed Spanish ships on his way home across the Pacific and captured the Spanish treasure ship, the greatest bounty of loot in British history. He was eventually acknowledged as the “Father of the British Navy.”

A Great Sea Saga

Grann’s well-structured bestseller vividly describes the HMS Wager’s impossible journey around Cape Horn through gale-force winds and more than 100-foot high waves and its fatal shipwreck off the Chilean coast. Grann may sometimes overwrite, and he repeats crucial insights, sometimes making his descriptions long-winded. But this is one of the great sea sagas, and Grann captures it. He delves into the leadership challenges Anson, a good leader, and Cheap, a bad one, faced amid the complexities of their time and their ships, including their society, politics, inadequate diet, diseases, and class issues. Grann probes revealingly and movingly into the psychology of leaders’ conflicts, human relations, and survival, making this an essential read for anyone compelled by sailing ships, colonial warfare, British history, or human resilience under duress.

In his Author’s Note, which outlines his exhaustive research, including many original sources, Grann writes, “It’s impossible to escape the participants’ conflicting, and at times warring, perspectives. So…I’ve tried to present all sides, leaving it to you to render the ultimate verdict – history’s judgment.”