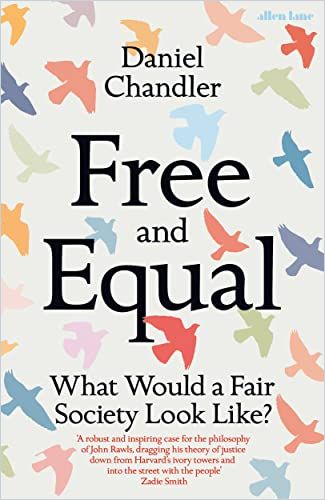

London School of Economics professor Daniel Chandler offers insights into philosopher John Rawls’s economic philosophy and how that philosophy is relevant today.

An Equitable Economy

London School of Economics professor Daniel Chandler considers the works of philosopher John Rawls, positing that Rawls’s precepts inform today’s socioeconomic debates and policies. Rawls describes the basis for a coherent, systematic alternative to neoliberal free market economics, one whose foundation is reciprocity and solidarity, not utility.

John Rawls

Many regard John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice, published in 1971, as the most influential book in modern political philosophy. In that text, Rawls critiques the concept of utilitarianism — the notion that a society should work to ensure that the greatest number of people possible enjoy a commonly accepted level of well-being — and proposes an equally systematic alternative. He aimed to establish principles of fairness, and the tenets he developed gained extensive approval and acclaim.

Rawls starts with an incisive thought experiment: What sort of society — including its laws and social structures — would you build if you didn’t know what your role would be within that society? For example, what if you were a member of a religious, social, or ethnic minority in your hypothetical society?

If we chose our principles…as if behind a ‘veil of ignorance,’ they would be fair.

Daniel Chandler

Rawls’s thought experiment makes people consider fairness and empathy. Pondering the conflicts between the principles you value and the specific beliefs you hold encourages you to critique your default positions or change your convictions.

Rawls’s “maximin rule” holds that, when facing two options, both of which could arguably lead to a bad outcome for yourself or others, you should consider the worst possible outcomes for each option. Pick the option whose worst-case scenario seems the least dire. Consider, for example, a law that serves a Christian majority at the expense of a Muslim minority. If you belonged to that minority, wouldn’t you prefer a society that ensures no one suffers the absolute worst outcome?

If everyone considered the possibility that they could have been born into a group harmed by the laws, prejudices, or structures of their communities, most would seek to prevent the majority or the powerful from supressing individuals.

Rawls believeed no basic liberty is unconditional: Society may need to limit one person’s basic liberties to protect the liberties of others. For example, society must balance the right to free speech with the harm it could do to people, such as inciting violence or harassment, damaging democracy, supporting fraud, or — to use a recent example — harming public health through misinformation about COVID-19 and vaccines. Constitutions and laws must, in turn, enjoy protections via a robust, independent, and nonpartisan judiciary.

“Difference Principle”

Rawls stated that people must tolerate and accept that a free society maintains a “reasonable pluralism.” This means that others are allowed to hold views you might disagree with, and vice versa.All should prioritize laws — or the absence thereof — that protect and balance the different basic liberties of everyone.

At the heart of this approach is a commitment to resolving our disagreements by appealing to public reasons (political values that our fellow citizens can share) rather than to our personal moral or religious beliefs.

Daniel Chandler

Rawls believed that no society can ignore economic inequality if it wants to maintain its government and institutions. Rawls’s “second principle” asserts that all individuals should have an equal opportunity to achieve positions and careers that provide higher incomes. People should gain prized positions due to merit and effort.

Rawls’s difference principle says the only justification for inequality in society is whether it improves life for the least well-off. The difference principle seeks to maximize the size of the slice of the pie going to the least in a society.

Rawls’s “just savings principle” asserts that society should consider fairness and the moral obligation between generations. In 1971, Rawls was thinking about intergenerational material wealth and how consumption today should not come at the expense of future generations.

In a democracy, everyone has one vote. But to varying degrees, the wealthy influence government policy through political donations and media ownership. This concerned Rawls deeply. But he insisted that the right to express political preference through donations is one basic liberty among others, and limiting it might impinge on other rights. Rawls believed that, for a society to reach fair compromises and solve its inevitable disputes, it needed a “civil and respectful culture.”

Equitable Economy

Technology now enables managers to use online interaction and surveillance to control and monitor employees.The difference principle cautions that workplace hierarchies and large companies are justifiable only if they produce a prosperous society for all.

Worker representation imparts feelings of loyalty and motivates employees to work harder and contribute more to business improvements. The cooperative model makes employees co-owners of the companies that employs them.

The difference principle calls for a proactive role for the state in bringing about widely shared prosperity, not only through taxes and transfers but through how we organize our economic institutions in the round, from the education system to the distribution of ownership and the balance of power between workers and owners.

Daniel Chandler

The levels of inequality in most rich countries are far in excess of the conditions described by the difference principle. As the COVID-19 pandemic revealed, low-wage work can prove every bit as important to society as highly paid jobs, and a spirit of reciprocity and unity is more healthy and desirable than is an extreme meritocracy combined with a welfare state.

Progressive government policies enable greater social mobility, which, in turn, yields less inequality. When all parents feel confident about their offspring’s standard of living, the wealthy feel less compelled to give their children special opportunities that the poor can’t afford.

Review

Professor Daniel Chandler provides erudite insights into Rawlsian thinking. He seeks to introduce and guide 21st-century audiences to the philosopher’s primary principles and their usefulness today, and he offers ideas on translating Rawls’s principles into actions. Readers interested in political economy, whether students of Rawls or newcomers to his work, will appreciate Chandler’s astute approach to these more-relevant-than-ever themes.