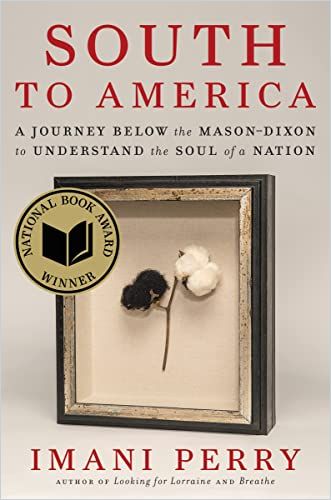

National Book Award winner and Harvard University professor Imani Perry provides a poignant perspective on the American South, past and present.

The South

Using the lens of her Black identity, Harvard Radcliffe Institute and Harvard University professor Imani Perry — whose books include May We Forever Stand and Breathe: A Letter to My Sons — provides a personal tour through today’s southern American states. Perry uses historical stories from Black American history to set a context for the present.

In this National Book Award winner, she explains that the South holds the roots of what it is to be American. Home to a complex culture sprouted from a conflict-ridden history, it is where the founding fathers dismissed the rights they codified, the past refuses to go away, and class and racial stereotypes still seem to shape the future, but still, there is progress and hope.

People tend to tell US history linearly, Perry explains, and often discount the South as a region because of its shameful history of slavery. This narrative choice ignores twin truths: The racial and class-based stratification of America’s population – in various forms, past and present – does not “belong” to the South alone. And, in fact, the South can tell you a lot about the entire nation, because, in many ways, it influences the country’s direction.

Appalachia

Appalachia is rife with stereotypes – poor people, bluegrass music, coal mining, and farming. Mining gave rise to a labor movement, but white workers resisted rallying for justice with Black workers. Today, opioid abuse and poor diets arise from and contribute to the region’s conflicts. As she moves throughout the region, touching base in a wide variety of places, Perry illustrates the contrast between a shared culture and that culture’s racial and class divisions.

In the 1800s, Black people played pivotal roles in Louisville, Kentucky, but powerful white people controlled local society. Too often, people brush slavery aside when discussing, for example, Kentucky’s distilling industry, whose emergence hinged on slave labor.

Virginia’s founders both sought and suppressed liberty, bespeaking the divide between power and freedom. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, the site of an 1859 uprising against slavery, eventually became a center for work on racial justice and home to a school for Black students.

Washington, DC’s lack of Confederate monuments suggests that it distances itself from slavery. Today, the District – home to Howard University, a historically Black college, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture – is gentrifying and becoming less Black. Whether it remains part of the South is in the eye of the beholder.

Everywhere one turns in DC, one witnesses the history of the South.Imani Perry

Maryland technically is part of the South, but it doesn’t share the Deep South’s culture. Before abolition, it had the greatest number of free Black people. Yet, visiting its historic homes where enslaved people once lived and worked highlights the region’s deep ties to the slave trade. The Great Dismal Swamp concealed thousands of people who escaped enslavement. Here, the question of what is preserved and what is lost to time applies to the ongoing evolution of American institutions and identity. Maryland’s narratives often evoke the way people covered vice with a veneer of virtue. Perry suggests that studying this history more deeply can show contemporary leaders the importance of being deliberate about how they shape the future.

Alabama

Huntsville, Alabama was home to an arsenal that displaced hundreds of Black families. Later, the town welcomed a rocket facility that gave rise to NASA. The wealth invested in the space race contrasts with the poverty of local people. Faith and social traditions interpret and shape Huntsville’s reality, though its different population groups diverge over which traditions to preserve.

Huntsville’s Seventh Day Adventist Oakwood University reflects the course of race relations in 20th-century America. It grew with the rise in the number of Black people attending college in the late 1910s. In 1931, its students protested against the false rape allegations against nine black youths in the Scottsboro case, and, in the 1960s, they participated in the civil rights movement.

Birmingham, Alabama, is a city of coal, steel, and civil rights. Perry’s personal story begins here as the child of civil rights activists who organized both Blacks and whites to oppose unjust, abusive imprisonment, police brutality, and the lack of Black land ownership. Birmingham’s struggle for justice and liberation can’t be reduced to just the 1963 marches. Perry sees Alabama’s history as a story of long-term “forbearance,” which sometimes led to change and, other times, kept people mired in place. Oppression remains, she says, but the tactics used to maintain it have evolved.

Mobile on Alabama’s Gulf Coast bears marks of slavery, poverty, and segregation.The sunken wreck of the slave ship Clotilda and the community of Africatown, founded by its former inmates, point to the poignancy of being ripped from a homeland, a theme Perry treats empathetically.

North Carolina and Tennessee

In North Carolina, academia and industry set the tone. The religious right is entrenched and promotes racial animus. Silent Sam, a statue of a Confederate soldier that stood on the University of North Carolina’s Chapel Hill campus until protestors took it down in 2018, exemplified the endurance of Confederate culture. The University has stored it for safekeeping as a relic of history.

Nashville, Tennessee reminds visitors of stereotypical Southern TV shows. The city is home to Vanderbilt University, historically Black Fisk University, and Pearl High School, a segregated school that became a portal to higher education, though Black students still face an uphill slog to pursue higher education and escape poverty.

The reach of institutions that nurtured Black children in the wake of a white supremacist order is much broader than most of us… realize.Imani Perry

In Memphis, riots sparked by the unjust treatment of Black garbage haulers led to unrest and police brutality in 1968. The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was in town to participate in related protests when an assassin murdered him. And, as Perry points out in the kind of cultural contrast she has mastered, the town erected a monument to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, the following year.

Coastal Cities

Georgia’s southeast coast is home to the distinctive Gullah Geechee culture, created by the descendants of slaves. Now thriving tourism has moved into the once-quiet coastal islands. Upstate, Atlanta, Georgia, is a hub for air travel, Coca-Cola, and hip-hop, though grit remains behind the sheen. However, urban Atlanta, with its historic Black colleges, isn’t the only place in Georgia to seek Black culture. In historic Savannah, a remarkable collection of the works of Black artists pays tribute to a rich culture. The First African Church of Savannah, established in 1773, provides an example of how enslaved people maintained African traditions.

So many people live in the ruins of the American drive for prosperity.Imani Perry

In Charleston, SC, former slave Denmark Vesey planned an 1822 slave uprising for which he was hanged. This historic town is also where white supremacist and neo-Nazi Dylann Roof sat in on a prayer meeting in 2015 and murdered the Black churchgoers who had welcomed him.

Perry finds that Florida “is a world of its own.”Indigenous cultures resided there before French, Spanish, and British colonialism arrived. The Seminoles and their Black sympathizers fought for their rights in the early 1800s. Formerly enslaved people established America’s first incorporated Black town, Eatonville, Florida in the late 1800s.

Today, Florida has a mix of vital Latin communities. Miami’s Black neighborhoods have strong Cuban and Caribbean cultures. Orlando’s flourishing Puerto Rican community demonstrates that Hispanics can’t be grouped into a single political entity. They remain politically marginalized, Perry reports, despite their strong, growing presence in much of the United States.

New Orleans, Louisiana, “the most Southern of American cities,” still carries scars of slavery. Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, as residents lost homes and businesses, and the government left them without basic necessities, but Black culture persists. Louisiana’s segregation laws fostered the development of Black schools, hospitals, and places of entertainment, but historically, the divide between the races has been blurred here more than elsewhere.

Jackson, Mississippi is a proudly Black state capitol. Oppression continues in Jackson, but now it affects immigrants from Latin America as well as the descendants of enslaved people.

The Black Belt

The Black Belt, a crescent of rural counties with mostly Black residents and a history of growing cotton,stretches from Virginia to Arkansas. Blues music captures the mood of this region. It speaks from the heart and carries hope.

This is the place…we mean when we say ‘the South’ as a historic location.Imani Perry

Both Black and white people tended to migrate away from this area, but it has a strong pull of home. The story of Bob Zellner, a white civil rights activist whose father abandoned the KKK after positive interactions with Black people, illustrates the region’s ongoing complexities of race and affiliation.

A Perceptive Overview

In this 2022 National Book Award winner, Perry shapes her readers’ sense of what the South – and the nation – has been, is, and might yet become as she relates and interprets the complex evolution of race relations and culture in the South over time. Despite offering her perspective on many historical reasons to fall into bitterness or despair, Perry keeps her spirits high and intends for her tour to elucidate powerful historical reasons for Black pride and for her community’s belief in America as a place of racial redemption. This is a superb overview for high school and college students of any race and, most particularly, for their parents.