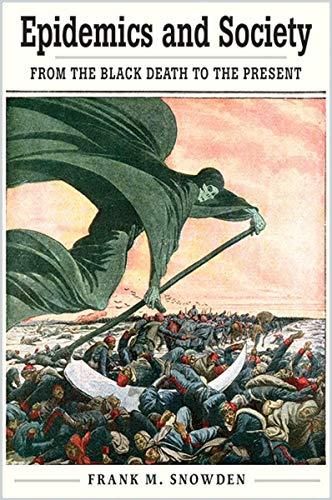

Yale University’s Frank M. Snowden brilliantly discusses centuries of epidemics and their societal effects.

A History of Epidemics

Diseases shape history

In this timely and engaging history, Frank M. Snowden, the Orrick Professor Emeritus of History and the History of Medicine at Yale University, reports that the world faces epidemics of emergent diseases – such as COVID-19, Ebola and HIV/AIDS – and of resurgent ones, like cholera and tuberculosis. He discusses the ways in which diseases have shaped history as powerfully as “wars, revolutions and economic disasters.”

The Wall Street Journal called this a “brilliant and sobering” look at the history and human costs of pandemics. Snowden’s other books exploring the impact of disease on culture and society are Naples in the Time of Cholera, 1884-1911 and The Conquest of Malaria: Italy, 1900-1962. Worthwhile – less academic – works on similar topics include John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza and Laura Spinney’s Pale Rider.

Snowden’s central theme is that epidemic disease drives social change as does war or economic collapse. He cites the modern epidemics of Ebola, SARS, HIV/AIDS and COVID-19, as well as the persistence of malaria, cholera and tuberculosis. He notes that when the novel coronavirus pandemic emerged in early 2020, the world was, typically, unprepared to mount a quick counterattack. This is true even though fully 335 new diseases emerged from 1960 to 2004. Epidemics often incite fear, religious fervor, artistic expression and the impulse to cast blame.Today, Snowden reports, “the National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine says the West faces its biggest risk ever from infectious diseases.”

Bubonic plague

Snowden shows three surges of the plague, beginning in Africa from 541 AD to 755. The second outbreak spread rapidly in Europe and ran from the 1330s to the 1830s. The third plague pandemic started in Central Asia in 1855 and, as Snowden explains, the disease remains a threat.

In many respects, plague represented the worst imaginable catastrophe, thereby setting the standard by which other epidemics would be judged.Frank Snowden

Coercive controls to contain the plague included unprecedented uses of state authority to regulate everyday life. In the second plague pandemic’s early stages, European countries tried to contain the Black Death through “institutionalized public health.” In Venice, local authorities seized ships to clean them while isolating their passengers and crew for 40 days of quarantine.

Smallpox

Snowden discloses that in the 17th and 18th centuries, smallpox may have caused 10% of all deaths in Europe. In 1796, Britain’s Dr. Edward Jenner became the first physician to confirm through experimentation that being infected with cowpox provided immunity to smallpox. Starting in 1959, vaccination on a massive, international scale eradicated smallpox. Snowden cites this effort as the most admirable, practical use of medical science.

Epidemics defeated Napoleon

Throughout his book, Snowden paints a graphic picture of the impact of epidemics on warfare. In two instances, Napoleon provides his case histories. The author reflects on Haiti, formerly Saint-Domingue, which declared independence from France in 1804 after enslaved Africans there rebelled. Yellow fever killed 45,000 of the 65,000 soldiers whom Napoleon Bonaparte sent to suppress the rebellion. In 1812, Snowden recounts, Napoleon invaded Russia with an army of 500,000 men – facing a brutal winter, dysentery and typhus, only 75,000 survived.

Louis Pasteur

Snowden describes in stirring detail how the Paris School of Medicine exerted revolutionary influence from 1794 to 1848. For example, the author names René Laënnec, who invented the stethoscope in 1816. Snowden also celebrates a more famous name, French chemist Louis Pasteur, who published studies from 1857 to 1876 showing that milk, wine and beer spoil due to bacteria. He discovered that heating wine and milk – “pasteurization” – prevented spoilage by killing bacteria.

Nobel Laureate Joshua Lederberg famously argued that in the contest between humans and microbes, the only defense humans possess is their wits. One could add to Lederberg’s formulation our capacity to collaborate – if we so choose.Frank Snowden

In his studies of anthrax and chicken cholera, Snowden marvels, Pasteur helped establish the germ theory. By the late 1870s, this was the prevalent understanding of disease. Pasteur also discovered that putting disease-causing bacteria into the body after attenuating, or diminishing, its virulence provides immunity. Snowden offers Pasteur as a true hero; readers will be hard-pressed to disagree.

Another hero is Scottish professor of surgery Joseph Lister, who demonstrated that if surgeons wash their hands and sterilize their instruments, they reduce the risk of infection.

Cholera

Seven cholera pandemics have erupted since 1817. The seventh, Snowden notes, started in 1961, and – this may surprise some readers – remains ongoing in Africa, Asia and South America. Cholera spreads through oral-fecal transmission in locations with contaminated drinking water, malnourished people, widespread poverty and crowded housing, and it causes as many as 143,000 deaths a year.

Polio

Infantile paralysis, or polio, initially mostly afflicted children, but from 1890 to World War I, “modern polio” victims came to include young adults. Snowden unveils the saga of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine, which won government approval in 1955. Albert Sabin’s live oral polio vaccine gained approval in 1962. Snowden laments that polio has proven less vulnerable to vaccination than smallpox. Among his recurring points is that humans have defeated very few epidemic diseases.

HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS still has no cure, Snowden reports, but antiretroviral treatments are extending lives by preventing immune system collapse.

The responses of populations reflected how they interpreted their encounter with disease, or – in a more recent phrase – how they ‘socially constructed’ their experiences.Frank Snowden

With his overarching attention to tracing trends that link epidemics to each other, he adds that the AIDS epidemic weakened expectations that science could eradicate infectious diseases.

Antibiotics

Dr. Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, warned in 1945 – and Snowden here echoes his warning – that the misuse of antibiotics leads to resistant bacteria. Bacterial resistance to existing antimicrobial drugs is pushing society closer to a future without a defense against new strains of diseases like tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS.

SARS, Ebola and COVID-19

In 2002, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) became the first new disease of the 21st century. Subsequently, the Ebola epidemic in 2013 took 11,325 lives. SARS and Ebola revealed a global lack of planning and preparation for fast-spreading diseases.

Of all the issues raised by COVID-19, the most important is preparedness.Frank Snowden

This is further evidenced by the novel coronavirus pandemic that broke out in 2020. Snowden added a new foreword to this 2019 book offering a preliminary analysis of COVID-19. Readers may hope for further coverage from the professor as the next chapter unfolds in the tragic history he knows so well. For now, he displays scant optimism concerning the human capacity to defeat possible emerging epidemics.

Erudition

Dr. Snowden is a fount of classically educated erudition. Though this review – of necessity – focuses on the most salient and readily digestible facts Snowden presents, the true greatness of this work emerges from his highly engaging ideas, his interpretations of history, and the way he links human reactions to epidemics and medical discoveries across centuries. His informed, non-linear conclusion-drawing will inspire and amaze. This is an enlightening, groundbreaking and necessary work, a pleasure to read from start to finish.