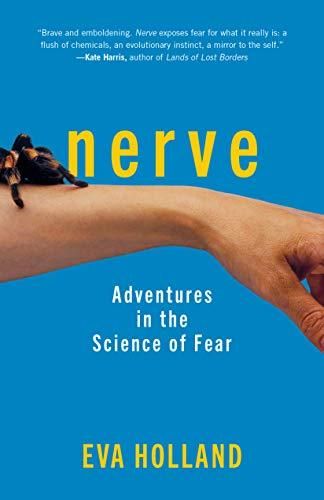

Journalist Eva Holland explores – with admirable candor and charm – the origins of her inescapable fears and the therapeutic paths she followed to minimize them.

Coping With Fear

Essayist Eva Holland knows fear, from a fear of heights to terror about driving that came on after multiple car wrecks. These paled in comparison to her primary, visceral fear that her mom would die. When Holland’s worst nightmare came true, she sought to discover the nature of fear and its origins. Could she conquer fear through psychology and science? Part memoir, part history, part scientific inquiry, Holland’s exploration provides hope for those seeking to overcome their fears.

Her Worst Fear

Eva Holland was on a canoe trip in Northwestern British Columbia when she received the message she’d feared since childhood. A fisheries officer piloted a boat to Holland’s remote campsite, leaving a note that changed Holland’s life: “Eva Holland you must call Nathan immediately regarding your mother.”

I was afraid that I would hurt her, afraid that I would lose her and afraid that, in losing her, I would become like her. I admired her, but I didn’t want to carry the same sadness in my own life.Eva Holland

After her mother’s death, Holland became paralyzed with fear on an ice-climbing expedition. That inspired her to investigate how to defeat or push through her fears.

Primary Emotion

An immediate threat unleashes fear. Inspired by a distinct external stimulus, fear differs from anxiety, which emerges from within. Doctors have sought to alleviate patients’ fears since at least 400 AD, when Hippocrates prescribed special diets, exercises and even poison to reduce what he called black bile.

Fear is, for most of us, simply part of being alive. Eva Holland

In Southeast Asia’s Hmong culture, for example, fear embodies in a nightmare demon, the dab tsog, that sometimes causes sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUND). Many cultures feature legends about murderous, nocturnal evil spirits.

External Stimuli

Holland cites neuroscientist Antonio Damasio and explains how he distinguishes between feelings and emotions. Feelings are ineffable manifestations of the mind’s expression; emotions are quantifiable bodily responses. Experts believe fear emerges moments after something triggers a bodily response. You experience an external stimulus, such as a scary sound in the night. The auditory input goes from the ears to the cranial nerve to the brain, and then from the thalamus to the amygdala to the hypothalamus.

Messages race along the axons throughout your body, from synapse to synapse to synapse, carrying the news of potential danger to your organs, to your skin.Eva Holland

The sympathetic nervous system gets the message. Your pulse races, your breathing becomes shallower, blood rushes to your muscles, and you may start to sweat. After the brain receives and processes information from the body, you become aware of feeling afraid.

In post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a previous experience lodges in the mind. It reasserts itself at inappropriate moments and obviates the brain’s capacity to tell the difference between a risk and a safe situation. Even a seemingly mundane experience can inspire PTSD.

Exposure Therapy

After her near-disastrous ice-climbing expedition, Holland tried exposure therapy. Exposure therapists maintain that if people encounter what they fear without dying, their fear may subside. At indoor climbing gyms, Holland forced herself to climb ever-higher until she felt tightness in her chest and her pulse pounded. Holland saw her new ability to push past her fear of heights as a “panicked success.

Repeatedly terrorizing myself wouldn’t solve anything; it wasn’t enough to scramble through with wild eyes and a pounding heart. I had to learn to stay calm.Eva Holland

Holland spoke to psychiatrist Edna Foa, who suggests that the fearful brain has a “structure” that links a stimulus – in Holland’s case, heights – to a fear reaction. Repeated exposure helps build a new structure that transmits the message that you can make it through a fear-inducing situation. If you still feel panic as you push past your fear, the new structure hasn’t yet replaced the old. To create a new structure, you must experience the fear stimulus and remain calm.

Propranolol

Holland turned to psychologist Dr. Merel Kindt, who believes fears are malleable, and that you can open them up and rework them. Think of fear as an impression you make in wet cement. According to former theories, after the cement dries, you cannot erase the fear. Kindt’s therapy – using 40 milligrams of propranolol, a beta blocker – works by reopening the fear and smoothing over the frightened response in her patients’ brains.

My chest was tight, my breath short and fast. I gulped for air. Kindt brought me a bottle of water and a single pill.Eva Holland

Kindt and Holland went to a fire station, where Holland climbed onto a ladder truck’s platform. The platform rose in the air, shaking in the wind. When Holland felt sufficient fear, firefighters lowered the platform. She received a dose of propranolol, and she felt calm. Kindt told her to avoid thinking about the incident and to get a good night’s sleep. She wanted Holland’s memory of scaling a great height to consolidate with her propranolol-inspired sense of calm. The next day, Holland went up on the ladder platform again. She was elated to discover that her fear of heights appeared to be gone.

Rapid Eye-Movement Desensitization

Psychologist Francine Shapiro developed rapid eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR) in 1987. Shapiro noticed that when she brought a pervasively negative thought to mind, then moved her eyes back and forth several times, the thought “lost its negative power.” After experimentation, Shapiro designed research studies that returned promising results. Clinical studies confirmed that EMDR treatments reduced “flashbacks, nightmares” and “panic” in 100% of research participants.

Many of us carry traumatic memories around with us every day – memories that have the potential to insert themselves into our minds at the worst moments, hijacking our ability to determine threat from safety.Eva Holland

Shapiro taught the method to other therapists. Her idea faced intense scrutiny, but evidence upheld its effectiveness, including with cases of PTSD. Since Holland’s fear of driving had elements of PTSD, she sought EMDR.After several sessions, her fear of driving subsided.

Holland felt her multi-pronged quest to understand and reduce her fears mostly succeeded. She felt she could now explore the world without fear stopping her, but also realized that, if she chose, she could just relax at home with a good book.

Escaping Fear

Holland writes with self-deprecating candor, while understanding herself to be her own – and her readers’ – guinea pig. She ably walks the line between vividly describing her emotional experiences and remaining objective about her responses to various therapies. This makes Holland eminently relatable while bolstering her journalistic credibility.

I wondered if my fear might now be less potent than I had imagined, that it might in the future hold less power over me than I had allowed it to in the past.Eva Holland

Her writing about her fears of her mother’s death and her life afterward prove particularly moving. Holland’s openness about her terrors – and her frustrations with them – will connect you to her quest to escape them.

Eva Holland also wrote Mussolini’s Arctic Airship. Other works on mastering your states of mind include The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman; Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds by David Goggins; and 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote to Chaos by Jordan B. Peterson