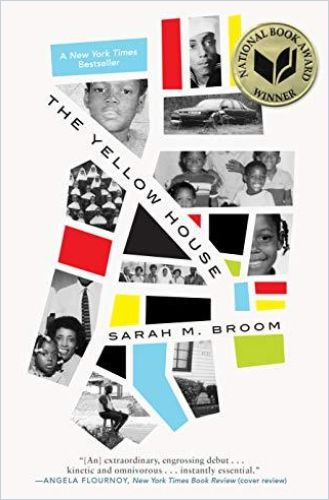

National Book Award winter Sarah Broom’s evocative, singular memoir describes her family’s close-knit poverty and the New Orleans house at the center of their lives.

What Is Home?

The Yellow House

New Orleans native Sarah M. Broom, who garnered the 2019 US National Book Award for this memoir, paints a loving portrait of the family, house and city of her birth. Hurricane Katrina – which Broom calls the “Water” – tore all three apart in 2005.

In a time of increased toxic tribalism in the United States, Broom presents an extraordinary, moving chronicle of the most nourishing kind of tribe – a family linked by blood and mutually assumed responsibility. In her consistently matter-of-fact voice, Broom depicts how working-class and poor Black Americans don’t even think of asking the government or civic structures for help; they know none is forthcoming. Instead, she remembers, the people in her family looked after one another. Or, as she wrenchingly relates, sometimes failed to do so.

Major magazines that have published Broom’s work include the New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, The Oxford American and O, The Oprah Magazine. She won a Whiting Foundation Creative Nonfiction Grant as well as the National Book Award, and she was a finalist for the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Creative Nonfiction.

4121 Wilson Avenue

In 1961, Ivory Mae Broom, Broom’s mother, purchased 4121 Wilson Avenue, New Orleans East. Broom regards with reverence how the Yellow House – in the neighborhood of New Orleans East – witnessed the lives of the family members who came before her and provided the context of her own life.

Broom delineates a family tree that grew through blood relationships and need – cousins who were as close as sisters and neighbors whom Broom treated as mothers. She dedicates her book “with love and heart” to her mother, Ivory Mae, grandmother Amelia (Lolo) and her mother’s sister, Auntie Elaine.

Broom notes that she was the youngest of 12 siblings and step-siblings, some born in the 1940s. Ivory Mae raised the children and ignored differences in their parentage.

[My mother] would, in fact, always insist that there was no difference among any of us children – that our having been raised by her made null any paternal or maternal differences.

In 1958, Broom discloses, instead of starting 11th grade, Ivory Mae married Edward Webb. Baby Eddie arrived in 1959, and Michael came in 1960. A car struck and killed Webb in 1960, when Ivory was pregnant with Darryl; the driver wasn’t arrested, though Broom says flat out that the family believes his death was a racist murder. This resonates as a hard fact of life for Black New Orleans’ residents.

Ivory Mae remarried in 1964 to Simon Broom, a widower 19 years her senior. He had three children, Simon Jr., Deborah and Valeria. Ivory and Simon together had Carl (called “Rabbit”), Karen, Troy, Byron, Lynette and Sarah, the author. As a family, they moved into “the Yellow House.”

“Unruly Child”

Broom explains that Simon Broom – her father – died when she was six months old.

No one who came before me, the people on whose memory I must rely, has a thing to say about my father’s reaction to me for the six months he and I lived in the same house, which is technically the six months I knew him.

Broom then lists Ivory Mae’s responsibilities: She managed the house, the bills and driving. Six of her children were adults, two were teenagers, and four required her full attention. Broom casts the Yellow House as the “thirteenth and most unruly child.” The author admires the way Ivory worked with Auntie Elaine as a nurse’s aide, studied for nursing exams and earned “a commercial sewing degree” at Louisiana Technical College.

Five locations delineated Broom’s childhood world: her grandmother’s home, the family car, the Yellow House, church and school. She avows that outsiders were not welcome.

By the early 1990s, Lynette left for college, which granted Broom her own room. Grandmother Lolo moved in, and Darryl developed drug problems.

Broom went on to attend student exchange programs at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and William Paterson University. Returning home seemed like a regression. When Broom’s childhood friend Alvin died in 1999, she returned for his funeral. After that, she never spent another night at the Yellow House. This moment raises mixed feelings for Broom; she had separated herself from that place and its dynamics, yet she always thought the house would be there for her.

Hurricane Katrina

The “Water” hit New Orleans on August 29, 2005. Broom and Lynette were in New York City. Lolo evacuated with a bus full of patients from her nursing home; Broom tells of the family’s panic when they couldn’t find her for a week. Ivory Mae fled to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, which was also flooded, and then went to Dallas.

Broom tracks the trauma of the family’s diaspora, which – she underscores – was entirely typical of New Orleans refugees. Her sister Valeria, her daughters and grandchildren got to Ozark, Alabama. Michael and Carl were stranded in the water around the Yellow House. Michael left and flew to San Antonio. Carl and his two dogs survived for two weeks amid the destruction.

Those images shown on the news of fellow citizens drowned, abandoned and calling for help were not news to us, but still further evidence of what we long ago knew.

Broom joined her mother, Ivory Mae, and much of the family at her brother Byron’s home outside San Francisco. He sent airplane tickets to his relatives and to a former neighbor who’d escaped the floods. Nine people filled this “shelter for the dispossessed.”

The family, Broom recounts, found Lolo in a Tyler, Texas, nursing home, where she died a month after the storm. “Grandmother’s house,” in Saint Rose, Louisiana became a refuge. Ivory and Auntie Elaine lived there, sharing a room.

Broom reveals that the city of New Orleans marked the Yellow House – along with 1,974 other homes – as structures at risk of collapse. She portrays the heartbreaking image of Carl guarding the home’s ruins. Ivory started a “Road Home” application to sell the house to the state and buy another home in Louisiana. As Broom laments, the application dragged on for 11 years.

“Dismemory”

Broom went to New Orleans in 2011 to write this book. Her French Quarter apartment’s spare room had once been home to enslaved people. The Quarter’s restaurants and hotels once banned Black visitors. Broom relates that Ivory Mae, then 71, stayed in the apartment with her – the first night she ever spent in the French Quarter.

This is the place to which I belong, but much of what is great and praised about the city comes at the expense of its native Black people, who are, more often than not, underemployed, underpaid, sometimes suffocated by the mythology that hides the city’s dysfunction and hopelessness.

Broom details the city’s high unemployment, low-paying hospitality jobs, and insufficient health and mental health services. She describes the permanent gulf between tourists and those who serve them. A 2011 discrimination suit, Broom explains, finally curtailed the endemic racist practice of giving Black residents lower pre-market valuation grants on their homes than those given to whites. Amid considerable change, Ivory continued to pursue her Road Home application. The family can’t rebuild the house, but Broom knows they will preserve its memory.

A brave work

Broom comes to grips with the joys and heartaches of her tight-knit clan. Broom’s evocative voice in this rare book portrays the wrenching effects of generations of poverty and her own battle to escape it. As Essence magazine wrote: “This brave work delves into such issues as poor housing, subpar health care, family bonds, personal erasure and survival.” It’s all that and more: You can’t stop reading Sarah Broom’s compelling voice.