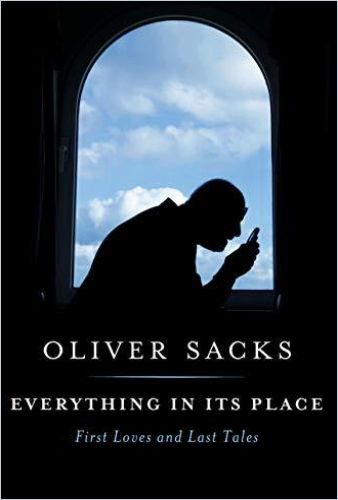

Best-selling neurologist and cultural touchstone Oliver Sacks’s final collection of essays on the fundamental mysteries of the human condition.

Oliver Sacks’s Final Words

The best-selling author, neurologist Oliver Sacks, MD, was a clinical professor of neurology at Yeshiva University’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine from 1966 to 2007 and held an appointment at the New York University School of Medicine from 1992 to 2007. In July 2007, he joined the faculty of Columbia University Medical Center as a professor of neurology and psychiatry.

For decades, Sacks’s insights into neurological conditions helped readers better understand the complexity and variety of the human mind. In this final essay collection, published after his death in 2015, Sacks demonstrates his range and his passion for science. As a child, he delighted in libraries and museums, both of which proved indispensable to his future career path. As a doctor in the New York City area, he treated thousands of patients with neurological conditions. Effortlessly elegant, elegiac and sweeping, Sacks’s last work is a fitting final chapter of a fascinating life.

When this posthumous collection emerged, the critical response was rapturous. The New York Times Book Review said of Sacks, “Life bursts through all of Oliver Sacks’s writing. He was and will remain a brilliant singularity. It’s hard to call to mind one dull passage in his work – one dull sentence, for that matter.” The Scientist wrote, “The Shakespeare of science writing might suffice, but Sacks ultimately defies comparison to bygone or even contemporary authors.” Readers will find Sacks’s usual panoply of human mystery, scientific inquiry and lively humor here in abundance.

Dreams

Sacks finds it curious that neurologists rarely inquire about patients’ dreams, because dreams can assist in diagnosis. Images vanishing from dreams, Sacks recounts, may be a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease.

It seems to me that only science – aided by human decency, common sense, farsightedness, and concern for the unfortunate and the poor – offers the world any hope in its present morass.Oliver Sacks

Finding magic in all medical conditions, Sacks notes that the unconscious mind might be more aware of neurological changes than any doctor can determine. Sacks offers his own dream – one that occurred when he was recovering from a leg injury. He dreamed that he walked using one crutch instead of two.

Alzheimer’s

Sacks discloses that, in defiance of widely held notions, Alzheimer’s patients usually have insight into their condition. The idea of self, Sacks says, remains until the late stages; for instance, the patient may recognize stories and songs. Here Sacks returns to and underscores his theme: Throughout your life, every action, thought and utterance is an expression of your selfhood.

Psychosis

Psychosis, Sacks explains, makes the sufferer feel like the most important person in the world. He argues that mania isolates people. Sacks offers this surprising rebuke to conventional wisdom: He says mania and depression are two expressions of the same impairment, not opposites on a spectrum.

Insane Asylums

Sacks explains that “asylum” means refuge; and that there have been asylums for the mad, the indigent and the criminal since the fourth century. In the 19th century, Sacks found that patients sometimes spent their entire lives in institutions, sharing community and purpose. However, Sacks laments that overcrowding, corruption and incompetence became common.

Sacks mourns that in the 1980s, deinstitutionalization put hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people on the streets. He offers a model for a different approach in Geel, Belgium, where households host mentally ill “guests,” who integrate into their community and gain respect and love. Otherwise, Sacks reminds readers, the mentally ill are among the world’s most marginalized citizens.

Gardens

Sacks regards Europe’s beautiful botanical garden as living museums. He believes that gardens restore and calm the mind, and can be more powerful than medication. He suggests that gardening becomes instinctual for Alzheimer’s sufferers. Being in nature fuels mental health and well-being; it changes brain physiology.

Those trapped in this virtual world [of smartphones] are never alone, never able to concentrate and appreciate in their own way, silently.Oliver Sacks

Sacks credits today’s obsession with technology as generating alienation and obliterating privacy. He holds that no one is alone in a virtual world, and no one can find the peace simply to exist. As technology fosters amnesia, Sacks finds it erodes the institutions of culture and history that unite people. He is adamant that the arts and sciences improve people’s lives and offer hope for a better future.

Only One

Oliver Sacks’s writing has evolved over the decades. Here he provides a more personal, less objective tone and spends less time detailing the complex science behind the phenomena that enthrall him. In other words, he has become more generous, present and readable. Sacks’s compassion and empathy form the very model that – as author Brené Brown, among others, continually reminds readers – makes up life’s crucial nourishment. Sacks’s nimble imagination and bottomless curiosity take the front stage here and offer one delightful surprise after another. Sacks, to put it simply, found great joy in the world, in humanity, in science and in the endless mysteries of existence. He shares that joy as a great gift.

Sacks’s wonderful, illuminating books include Gratitude, On the Move, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, A Leg to Stand On, Awakenings, Migraine, Musicophillia, An Anthropologist on Mars, Uncle Tungsten, The Island of the Colorblind and The Mind’s Eye. There is no one who thinks and writes like Sacks. If his voice speaks to you, read any or all of these titles.