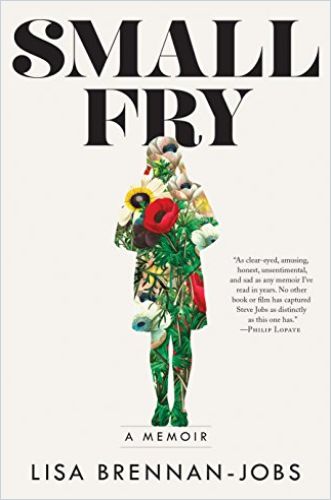

Lisa Brennan-Jobs writes with candor, skill and remarkably little self-pity about her complex and contradictory relationship with her renowned father.

The Eyes of a Child

Lisa Brennan-Jobs was the daughter of Steve Jobs’ former high school sweetheart. When he lost a paternity suit in 1980, the court ordered him to pay $385 a month in child support. He increased it to $500 and signed the documents only days before his company, Apple, went public, making him suddenly worth $200 million.

Thus begins Brennan-Jobs’ tale of her complicated relationship with her father. From their first acquaintance until his death from cancer in 2011, Jobs struggled to show love for his first child. She wonders why he lied about being her father and refused to admit he named his first mass-market computer, the Lisa, after her. Brennan-Jobs never devolves into self-pity; instead she ponders bigger questions: how did her relationship with her father work out, exactly, and why did she need his love so much?

When people speak and write about my father’s meanness, they sometimes assume that meanness is linked to genius. That to have one is to get closer to the other.Lisa Brennan-Jobs

Brennan-Jobs’s memoir was a New York Times and New Yorker Top 10 Book of the Year and a NPR, Amazon, GQ and Vogue Best Book of the Year. The New York Times Book Review called it, “Beautiful, literary and devastating.” Vogue described it as “a masterly Silicon Valley gothic.” The New Yorker said, “Mesmerizing, discomfiting reading… A book of no small literary skill.” And People found it “Extraordinary… An aching, exquisitely told story.”

Mom and Dad

Lisa Brennan-Jobs explains that when her mother, young Steve Jobs’s girlfriend Chrisann Brennan, became pregnant in 1978, Jobs stopped speaking to her. He provided no help until she sued him for child support in 1980. A DNA test, Brennan-Jobs reveals, proved Jobs’s parentage, but he did not meet his daughter until she was three years old.

Jobs took responsibility for Brennan and their child in 1982, when he reunited with his sister, the author Mona Simpson. Jobs respected his sister as a self-made woman who was famous in her own right, and he listened to her. Brennan-Jobs explains that when she was older she learned what Jobs admired most: independence. Mostly, she says, Jobs treated her as a companion and confidante. Her mother told her that Jobs loved her, but that he didn’t know he did.

Brennan-Jobs details how her father introduced her to his fiancée Laurene Powell, remembering that he grew angry with her when he felt she and her mother didn’t pay Powell sufficient attention.

We all made allowances for his eccentricities, the ways he attacked other people, because he was also brilliant, and sometimes kind and insightful.Lisa Brennan-Jobs

Brennan-Jobs recalls that she was hurt by a lack of affection from her father and Powell. When she expressed this to Powell and Jobs in a therapy session, Powell responded that she and Jobs were “cold people.”

Money and Fame

Brennan-Jobs describes how she and her mother subsisted on welfare when she was a child, even after Jobs became enormously wealthy. Brennan, her daughter writes, would call Jobs and beg for money. Later, Brennan-Jobs concedes, Jobs increased his support payments and gave Brennan occasional cash gifts.

There was a thin line between civility and cruelty in him, between what did and did not set him off.Lisa Brennan-Jobs

During her college interview at Harvard, Brennan-Jobs recognized that her accomplishments weren’t compelling, and she casually dropped that her father invented the Macintosh. The interviewer’s attitude instantly changed, Brennan-Jobs writes with both contempt and relief, and Harvard accepted her.

In a particularly telling story, Brennan-Jobs relates how Jobs once offered to buy Chrisann Brennan a house. She found a “fairy-tale house” she loved, but, the author reveals, Jobs bought it for himself and Powell.

She details that Jobs was frugal, particularly with food. His diet was strictly vegetarian with no dairy products, in order, he said, to maintain his body’s purity. Jobs, the author illustrates, was demanding, petulant and cruel in public, but he rarely faced repercussions. Brennan-Jobs says she knew that to avoid becoming a target herself she should not defend the people he attacked.

Loyalty and Loss

Brennan-Jobs divulges that Jobs, who was a college dropout, joked that it was more worthwhile to take his daughter to Hawaii than to send her to college. She laments that he never congratulated her on her Harvard acceptance, and that began their estrangement.

Near him was the safest place to be when he attacked someone else. Lisa Brennan-Jobs

Jobs, his daughter tells, became weirdly fixated on having her attend a Cirque du Soleil performance with him, Powell and their children. When she chose to spend the time with her mother instead, Jobs didn’t speak to her for months. He also took umbrage when Lisa didn’t invite him to her matriculation; after that, he refused to pay her tuition. In the biography on his website, Jobs did not include her in a list of his children.

Acceptance and Death

Steve Jobs frequently said he would become famous and die in his 40s. He never wore a watch because, he said, he did not like to be bound by time. When he knew he was dying of cancer, Jobs told his daughter that he regretted not spending more time with her. He wept, something Brennan-Jobs had rarely seen him do. She accepted his apologies.

After Jobs died, her mother assured the author that her father’s spirit followed her and loved being with her every moment. Brennan-Jobs writes without rancor that she didn’t believe it, but she liked the idea.

Not Such a Small Fry

Lisa Brennan-Jobs doesn’t come across as a small fry at all. She has a solid, amazingly observant voice, and she uses it to great emotional impact. In this memoir, part coming-of-age autobiography, part tribute to one of the world’s most influential innovators, Brennan-Jobs paints a touching portrait of a man who struggled to be a loving father.

At times Jobs was indifferent to her, even cruel, but the narrative never slides from observing and analyzing to blaming and castigating. Brennan-Jobs chooses instead to show the reader her father’s inner conflict: she was a mistake and, therefore, a blight on his ascent to greatness, but she was also his firstborn, and he loved her deeply. Readers usually less intrigued by the lives and families of influential people will be hooked by Brennan-Jobs’ candor, clarity and charm.

Other moving, perceptive childhood memoirs include Born a Crime by Trevor Noah and Educated by Tara Westover. Books offering insider perspectives on Steve Jobs include The Bite in the Apple by Chrisann Brennan and Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson.