With his usual literate empathy, Dr. Oliver Sacks details the effects of music on those with dementia, Tourette’s syndrome, Alzheimer’s and other conditions.

Music: Revelation or Damnation?

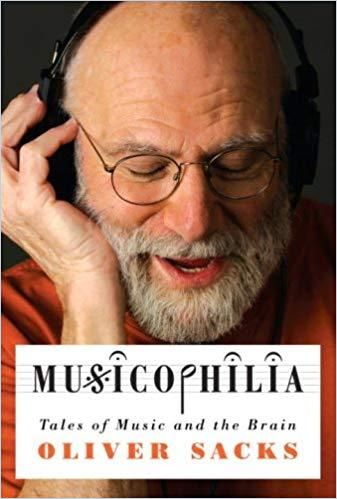

The best-selling Dr. Oliver Sacks (1933-2015) was a British-born neurologist whom critics described as the “poet laureate of medicine.” He’s best known for his many books featuring patients with atypical neurological disorders. Here Sacks explores – with his usual compassion and lyrical insight – neurological functions and dysfunctions pertaining to music and its power to inspire, heal and pacify. Sacks makes no secret of his own eccentricities regarding music and his soulful generosity welcomes and sustains the reader.

Maladies and Therapies

Sacks posits that aliens visiting Earth would be unable to decipher the singular role of music in the human experience. Music suggests a language, but has no self-explaining iconography. It emerges entirely from itself.

Whether people hear music from inside the brain or out, Sacks explains that it can cause some people to suffer seizures, and can bring on hallucinations for others. Musicians with synesthesia, for example, associate various senses with music – color, smell or taste.

Sacks offers “musicophilia” as an umbrella term for an array of maladies and therapeutic strategies for patients suffering from Alzheimer’s and amnesia, Parkinson’s, Tourette’s, strokes, frontal-lobe syndromes and other conditions.

Revelation or Damnation?

Sacks offers a panoply of compelling case histories. For example, Tony Cicoria, 42, a surgeon, was struck by lightning and had a near-death experience physiologically and neurologically. He woke up a few days later with a craving to hear piano music, especially Chopin.

There is an innate musicality in virtually everyone.Dr. Oliver Sacks

Then the music in Cicoria’s head changed. It was no longer Chopin, but Cicoria’s own music, as though Cicoria had become a human radio frequency. The music demanded to be played. He bought sheet music and studied notation. He acquired a piano, got up at 4 a.m. to practice, went off to the hospital to work and practiced piano all evening. He had no choice.

Sacks describes this case history as he does every other case, with his singular, career-long tone of scientific objectivity, gee-whiz enthusiasm and profound empathy.

The “Mozart Effect”

Sacks cautions that science doesn’t know much about the brains of musical prodigies. Correlations do exist between anatomical development, the age at which a child begins musical training and the intensity of that training. Music can be as critical to a worthwhile education as writing, reading and math. That may explain the well-publicized assertion that listening to Mozart can result, at least temporarily, in more cognitive power. Sacks cites scientists, who, using magnetoencephalography, recorded “striking changes” in the left hemisphere of the brains of children who spent a year learning to play the violin compared to children with no musical training.

Imbalance of Powers

Sacks offers the case study of Martin, who came down with meningitis at age three. His illness led to limb spasticity, language disorder and odd behaviors. Martin suffered severe eye problems, a characteristic often found in musical savants. Along with absolute pitch, Martin possessed a “phonographic memory”; he could replicate any piece of music he heard, either on the piano or with his limited voice. Martin memorized 2,000 operas and each of Bach’s cantatas. His playing technique was impressive, as was his ability to improvise.

Being a savant is a way of life, a whole organization of personality, even though it may be built on a single mechanism or skill. Dr. Oliver Sacks

For Sacks, the fascinating question is whether meningitis restricted certain abilities and stimulated others.

Tourette’s Syndrome

Music may act as both jailer and liberator, even in the same person. Sacks points out that this is not uncommon for people with Tourette’s syndrome. Some music brings quick and lasting relief; very rhythmic music, unfortunately, may stimulate severe tics.

The power of music, whether joyous or cathartic, must steal on one unawares, as a blessing or a grace.Dr. Oliver Sacks

For example, English musician Nick Van Bloss suffers 40,000 tics a day. Sacks conveys Van Bloss’s ecstasy when he plays piano, because when he plays, his tics stop.

Music and Dementia

Sacks discusses the case of Woody Geist, who first showed signs of Alzheimer’s at age 67, and declined gradually. However, he never forgot the baritone line of every song he ever sang. For 40 years, Geist belonged to a 12-man a capella group. Not long ago, the group opened for the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes. On the night of the performance, Woody couldn’t tie his tie and got disoriented behind the curtain, but on stage he recalled his all parts perfectly.

Singing and Dancing

Sacks revels in the power of singing for dementia patients. It may improve their mood and, sometimes, their cognitive function for days.

Music is in the nature of being human, and for those with dementia, music is not a luxury, but ‘a necessity’.Dr. Oliver Sacks

Therapists often marvel at how music draws the attention of patients who are otherwise lost to the present moment. That’s particularly true of music that is familiar to them.

Beyond music, Sacks avows that dancing can draw out motor responses from the brain’s subcortical zones. Dancing, and especially dancing with other people, encourages consciousness at a primal level, in the subcortical – and so does drumming.

The Mind’s Labyrinth

The components of Oliver Sacks’s genius include his panoramic grasp of neuroscience, his understanding of the nuances of the human heart, and his rare and bottomless compassion for human frailty. Musicophilia – part memoir, part scientific study and part reflection – is Sacks’s note in a bottle, written almost as poetry and intended for people fascinated by the journey into the deepest levels of the human experience, as was Sacks.

As ever, Sacks loves long sentences and masses of abstruse detail, but he still reveals how tiny details can generate massive consequences in the universe of neurological damage or disorders. If you seek a fulfilling life, even if hobbled by a failing mind, Sacks urges you to dance and sing – with someone else, preferably – for as long as you can. His narrative gifts and overflowing heart will compel, astound and mesmerize you.

Dr. Oliver Sacks’s books include The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Awakenings; Gratitude; On the Move; Hallucinations; The River of Consciousness; and Everything in Its Place.