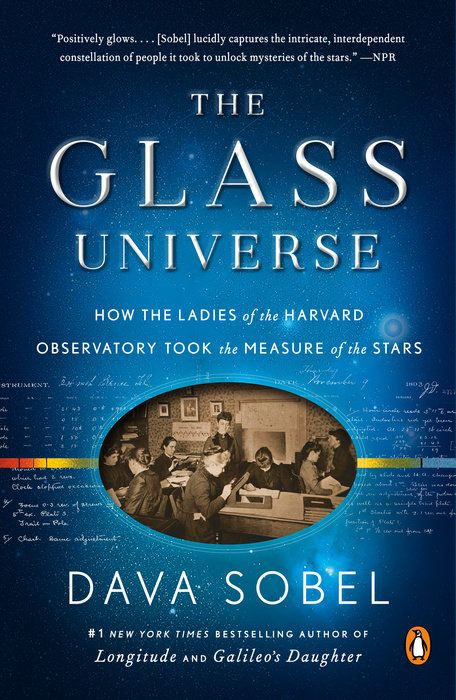

Prolific best-selling science historian Dava Sobel offers a detailed, revelatory history of women instrumental in the ascent and scientific dominance of the Harvard Observatory.

Women of the Stars

Women played a vital role in establishing, funding and studying the world-renowned Harvard Observatory’s catalog of stellar photographs. Dava Sobel’s remarkable seven-decade history covers The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra from its inception in 1882. Insightful, engaging and vivid, Sobel’s history charts the always difficult ascent of the Harvard Observatory’s women pioneers.

Margaret Draper

The Harvard Observatory director Edward Pickering focused the observatory on stellar photography.

Each photograph becomes, like a book, a storehouse of information. It may thus be constantly consulted in future years.Astronomer Edward Pickering

Margaret Draper donated a telescope and a building to house it, founded the Henry Draper Memorial fund, and inaugurated the Henry Draper gold medal – awarded by the National Academy of Sciences for “outstanding achievements in astronomical physics.”

Stellar Photographs

Pickering collected star data and needed staff for hours of labor to analyze the spectra. Williamina Fleming, a former maid, created a classification system, which evolved into The Henry Draper Catalogue. By 1891, having classified 10,000 stars, Fleming organized the photographic plates into a library with a card catalog. She oversaw 14 women analysts. In 1888, Antonia Maury, who held degrees in physics and astronomy, joined the group.

By 1889, Pickering discovered the first spectroscopic binary – two stars orbiting a common center of gravity – by discerning a second stellar presence on a spectrum. Maury discovered the second binary. The observatory published The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra in 1890.

As stellar photography unlocked secrets of the universe, Maury and Fleming were the first women to use it for that purpose.

Catherine Bruce

From the 1860s to World War II, astronomy enjoyed technological advances in stellar photography, telescope manufacturing and the weather statistics needed to choose the right locations for observing the skies.

When Pickering sought donations to create a groundbreaking 24-inch lens telescope, Catherine Bruce donated the requisite $50,000. The Bruce telescope produced outstanding plates. In 1897, Bruce sponsored the Catherine Bruce Gold Medal for men or women to celebrate lifetime achievements in astronomy.

When Draper died in 1914, her will bequeathed $150,000 – an enormous amount for that era – that helped make the Harvard Observatory preeminent.

Williamina Fleming

In 1893, Fleming came upon a rare nova – a new star – in Harvard’s spectra. It was only the 10th such star observed in recorded history and the first discovered through stellar photography. In 1899, Fleming became the official curator of the astronomical photographs and the first woman to have any title of any kind at Harvard. Her salary remained a fraction of that of her male colleagues.

Edward Pickering seems to think that no work is too much or too hard for me, no matter what the responsibility or how long the hours.Astronomer Williamina Fleming

After dedicating 30 years to the observatory, Fleming died in 1911.

Henrietta Leavitt and Annie Cannon

In 1895, Henrietta Leavitt and Annie Cannon brought academic qualifications and teaching experience to the project.

Leavitt discovered variable stars in the Magellan Cloud. Her study of 1,772 variable stars revealed what would become the period-luminosity law of astronomy – essential for determining distances in space. Like many women at the Harvard Observatory – Leavitt also had to do administrative work.

Leavitt discovered stars; Cannon changed the order of designations for cataloging stars in the Draper Classification system, which remains the standard.

Harvard president Abbott Lowell refused to give Cannon an official title, even though she was the greatest living expert in star classification. The League of Women Voters named her one of the 12 greatest women living in America, and she received an honorary degree from Wellesley College, her alma mater. Cannon became the first woman to receive an honorary science degree from Oxford. She founded her own woman’s award, the Annie Jump Cannon Prize, to be given biennially.

The Pickering Fellowship for Women

The Maria Mitchell Association, which funded women’s education, created the Edward C. Pickering Astronomical Fellowship for Women. The first Pickering Fellow, Mary H. Vann, tracked novae in the observatory’s collection from 1887 onward. Dorothy Block, another fellow, became the first woman to take photos through the world’s largest refractor, the 80-inch telescope at Yerkes Observatory.

The directorship position opened with Pickering’s death. Because they were women, Cannon and Leavitt were ineligible for the position.

Cecilia Payne

In 1924, Cecilia Payne – the first woman to complete her PhD at Harvard – joined the observatory, bringing her knowledge of quantum physics – a new scientific endeavor. Payne discovered that stars consisted almost entirely of hydrogen and helium. The broader astronomical community didn’t accept her findings until 1929, when a male astronomer concurred.

Of course women are different from men. Their whole outlook and approach are testimony to it.Astronomer Cecilia Payne

Payne became a full-fledged astronomer in 1927, earning $175 a month. She took over in-house publications, instructed graduate students and supervised research for a doctoral fellow – a man.

A renowned astrophysicist, spectroscopist and photometrist who taught and oversaw graduate courses and sat on three International Astronomical Union commissions, Payne didn’t receive a full professorship until 1956.

Pickering and Shapley gave women opportunities to excel in astronomy and treated female contributors with respect, regardless of their status.

Contextualizing history

Dava Sobel, a brilliant researcher and writer, brings bygone eras – with all their rivalries and pettiness, bravery and genius – to life in extraordinary detail. She contextualizes history adroitly, so any reader can absorb the mores of an era and understand how those conventions oppress anyone transgressing them. Accordingly, this is a tragic and heroic story. Heroic regarding the accomplishments of these extraordinary women and tragic regarding the meager rewards and recognition the institution to which they dedicated their lives granted them. Sobel, though outraged at these injustices, focuses on these women’s accomplishments and their remarkable perseverance and dedication to their mission. Sobel provides an inspiring, moving and educational saga.

Dava Sobel is also the author of Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time; Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith and Love; The Planets; and A More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionized the Cosmos.