Dan Albert, PhD, explores the history and cultural significance of the American automobile, and his own dread of a less romantic, more functional future of driverless cars.

Vroom!

Dan Albert, PhD, writes about the past, present and future of cars for n+1 literary magazine. The automobile, Albert reports, changed everything in American life: roads, homes, shopping malls, businesses, even movie theaters. In the face of impending catastrophic climate change, he notes, Americans still won’t get rid of cars; instead, they’ll create driverless, electric versions. With a deft and often bemused attention to historical detail, Albert illuminates how the American automobile created its own world and culture – one that shapes a driverless future.

Forbes wrote that the author “[brings] automotive history to life.” Keith Gessen, author of A Terrible Country, said that Albert “…is a unique voice in American letters – a historian of the car and its culture with a driver’s passion and a sense of the absurd.” And Publishers Weekly called this “…a perfect narrative for gearheads, but those who spend time behind the wheel will also surely enjoy the ride.”

Revolution

Americans comprise a country and culture, Albert says, reinvented in the 20th century to accommodate cars. He tells – and is hardly the first to do so – how automobiles shape Americans’ perception of the landscape, where they live, and where and how they work. Parents teaching their children to drive was, Albert remembers, a significant and memorable moment; getting a driver’s license meant becoming an adult.

The driverless car enters the obdurate auto-centric landscape built up over a century…The end of driving in America will have profound consequences for how we organize our lives.Dan Albert

Albert feels Americans are on the threshold of an era of driverless cars, which will forever change a nation shaped by the traditional American car. The end of driving, the author laments, will deeply affect how Americans live.

Henry Ford

Albert recounts how the US automobile emerged in the 1890s. Inventors put forward experimental cars; Albert lists William Morrison’s electric car; the Duryea brothers’ internal combustion engine; and the Stanley brothers’ steam-powered behemoth. By 1899, Albert found, Americans understood that cars were going to change the character of life radically.

By 1899, commentators and industry experts saw that the motorcar was destined to revolutionize American life in profound ways. Today, the feel of change is again in the air.Dan Albert

European members of a transatlantic, international elite, often with inherited wealth, Albert reveals, regarded cars as status symbols. Early in the 20th century, Henry Ford appeared; he wanted to sell, Albert makes clear, not to the rich or sophisticated, but to millions of US “hayseeds and yokels.”

Ford’s Model T appealed to rural people and, Albert insists, America’s mass embrace of automobiles resulted from Ford’s singular vision.

Alfred Pritchard Sloan

Albert details the saga of Alfred Pritchard Sloan, who became GM CEO in 1923. Albert defines Sloan’s purpose as making money, not cars; Sloan hired innovator Harley Earl, who created and defined the style of US cars for the next 50 years.

Along with everything else, the automobile revolutionized consumer lending and the culture of indebtedness.Dan Albert

By 1929, Albert writes, the United States had a car for every 4.5 people, and the government spent billions building roads. The author makes a crucial and often overlooked cultural point: The automobile brought common indebtedness to consumers, because Sloan understood the value of offering credit. Albert cites how the Great Depression brought a 75% decline in new car sales.

Interstate Highway System

Congress, Albert tells, passed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act in 1956, and construction started immediately. He recognizes that many blame the Interstates for “white flight” from urban centers and the deprioritization of trains and urban mass transit. The Interstate, Albert maintains, began in the Great Depression under Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In 1937, Roosevelt commissioned plans to create national highways running east to west. Albert reports that urban planners claimed a highway system connecting cities would abolish slums.

The interstates, however, were a throwback. To build them was to celebrate not the freedom and self-determination of the automobile but the power of the state to limit freedom for the greater good.Dan Albert

Albert calls the Interstate Highway System the largest and most expensive government undertaking in US history. At a cost of $116 billion in public money, Albert totals up 41,000 miles of highway which utilized more than a billion metric tons of rock, sand, cement and asphalt.

“Crashworthy”

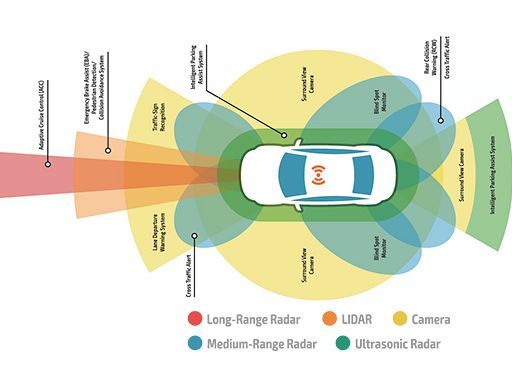

Albert wonders if the traditional concept of the American car is coming to an end. He believes riding in a driverless car will feel strange. He regards slanted windows, pillars containing airbags, high seat backs, and lap and shoulder belts as emerging from the dream of the “crashworthy car.” Fully 35,000 to 40,000 people die in American car accidents every year, yet Albert posits – with a strange, almost regretful romanticism – that people don’t die so easily in today’s cars that feature womblike safety features.

Adventure

Albert notes that anyone born since 2000 doesn’t care about or need cars. Albert makes a telling – if almost obsolete – point: The proliferation of social platforms means people have less need to connect in real time and space.

Detroit needs to figure out whether kids don’t like driving, don’t like shopping for cars, don’t care about cars or simply don’t need cars.Dan Albert

Albert mourns with surprising sentimentality that when people shift to driverless cars, they will relinquish automobiles as a source of adventure and creative expression; cars will no longer be machines people love.

Romantic

Albert is insightful, capable of singular perceptions and gripping historical narrative. Yet his oddly parochial romanticism undermines his poetic explorations and seems at odds with his intellectual bent. Further, Albert’s harping on the arrival of driverless cars does not reflect the technological truth that driverless cars remain far from fully functional and that manufacturers have not solved several fundamental problems. But, Albert remains about the smartest writer philosophizing about the car and American culture, knows and loves his subject matter, and, for all his brainiac distance, can offer enthusiastic, affectionate paeans to the automobile that will engage even the least sentimental readers.

Other intriguing works exploring the relationship between American culture and the automobile include Sarah A. Seo’s Policing the Open Road; Gretchen Sorin’s Driving While Black; and Paul Ingrassia’s Engines of Change.