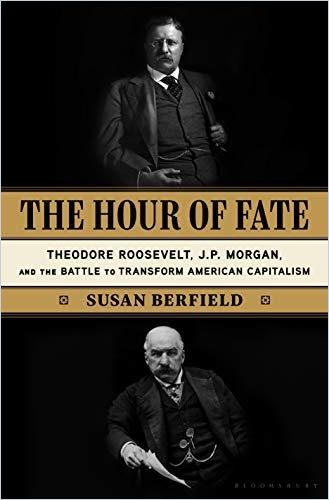

Award-winning investigative reporter Susan Berfield brings to life the brutal economic struggles of late 19th- and early 20th-century America.

Railroads, Trusts and Strikes

Susan Berfield’s illuminating history deftly captures turn-of-the-20th-century America’s economic drama. She ably depicts president Theodore Roosevelt and financier JP Morgan locking horns in antitrust and labor disputes. But Berfield’s most striking takeaway is that their struggle defined the United States’ economic future and showed how popular support and a strong president could upend long-held attitudes about capitalism and business.

The Christian Science Monitor called Berfield’s efforts “an extremely skillful blend of wide-canvas exposition and small-scale personal drama.” The Washington Post said, “Berfield’s story is about the past but also very much about the present, as our own Gilded Age raises old questions about inequality, plutocracy and what Roosevelt once called ‘that most dangerous of all classes, the wealthy criminal class’.”

Railroads

Berfield reveals that, during the last half of the 19th century, railroad companies accounted for 80% of the listings on the New York Stock Exchange and an estimated one-eighth of America’s total wealth.

Railroads altered the geography of opportunity. Their lines determined which towns became impoverished and which prospered.Susan Berfield

Berfield describes how the pace of change and brutal, often corrupt competition produced economic instability, periodic financial collapses and recessions. She offers the astonishing example that, from 1893 to 1894, 191 railroad companies – representing one-quarter of the country’s rail system – failed. This triggered a financial crisis during which 158 banks folded and unemployment reached 15%. Railroad practices inspired antielitist, antiurban and anti-East Coast populism, the author reports.

Trusts

Berfield launches her tale with banker JP Morgan’s belief that railroads needed stability to protect investors’ profitability and the economic system. She presents Morgan as a Wall Street power without peer in times before or since.

Morgan, the author recounts, set up trusts in which competing companies’ shareholders would turn over their stocks to trustees in exchange for certificates that entitled the holders to dividends from those trusts. Morgan thus assembles United States Steel, which Berfield identifies as the first billion-dollar company – one that makes Andrew Carnegie the richest man in the world. Berfield offers John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil as another example of a powerful trust.

Morgan believed the country’s financial and business structure should be controlled, and propped up when necessary, by the country’s financial and businessmen.Susan Berfield

When railroad companies had financial difficulty, Morgan would absorb them into voting trusts that he and his loyal trustees controlled. Berfield notes that within five years, “Morganized” railroads earned an amount equivalent to three-quarters of the US government’s total revenue.

Theodore Roosevelt

Berfield paints Theodore Roosevelt as a disruptive reformer with a meritocratic mind-set. He served as vice president to President William McKinley, but on McKinley’s assassination, the dynamic Roosevelt was unexpectedly unleashed on America.

Roosevelt and Morgan were bound for conflict…Roosevelt was a new kind of president. He believed American capitalism needed a guiding hand. So did Morgan. Each assumed it should be his own.Susan Berfield

Berfield details how, in 1902, President Roosevelt asked his attorney general to bring a case under the Sherman Antitrust Act against Morgan’s giant railroad holding company, thereby infuriating Morgan.

Berfield portrays Morgan in court denying that trusts restrained competition and claiming bigger trusts meant cheaper prices. But federal courts and then the Supreme Court, in early 1904, decided against Morgan.

Miners’ Strike

Berfield makes coal’s importance clear: It was virtually the entire source of heating for northern US cities. Coal fields in northeastern Pennsylvania, she shows, were under the command of the six railroad companies that shipped the coal. Berfield finds that mining bosses encouraged worker immigration from Eastern Europe, refused to recognize unions, dealt violently with strikers and cut wages during recessions. And many of the employers forced miners, the author adds, to buy consumer goods and explosive powder from businesses that the owners or managers controlled.

Miners went on strike in 1902, receiving $3 million in donations and, Berfield depicts, winning support from America’s press and intellectuals. But as winter approached, the United States faced a dwindling source of heating and steam power. Berfield reports that people felled trees in their gardens for fuel, and she breaks down how pneumonia and other respiratory diseases spread. Roosevelt forced a meeting between coal owners and union leaders, but as Berfield writes, mine owners refused to surrender what they felt was their right to run their businesses their way.

Morgan still felt betrayed by Roosevelt’s claims on his empire…Yet they set aside their mutual suspicion and antagonism to cooperate as the country faced the potential devastation of a winter without coal.Susan Berfield

Berfield details how Roosevelt turned to Morgan for help. Morgan used his influence to force mine owners to accept a presidential commission, which later found that the industry resembled a feudal kingdom. The author conveys how mine owners subsequently cut working hours and raised miners’ pay.

Lost Prerogative

Roosevelt won the 1904 presidential election in a landslide, and Berfield tells how he then took on the Beef Trust of six meatpacking companies. She relates how the Hepburn Act gave government more authority over railroad rates and that the Meat Inspection and Pure Food and Drug Acts were the first consumer protection laws.

Roosevelt said making change could be dangerous but doing nothing could be fatal.Susan Berfield

Morgan and his class of owners had lost the prerogative, Berfield asserts, to conduct business exactly as they thought best. She shows that, with the antitrust case and the miners’ strike resolution, Roosevelt had subtly but significantly changed the landscape and norms of American capitalism.

Portrait of an Age

This is more than a compelling history, told with a signature eye for the most important details and a journalist’s ability to illuminate grander themes with those details; this is a portrait of an age with remarkable similarities to the current economic climate, though Berfield is careful to never overemphasize the crucial parallels. She tells her fascinating story and lets you draw your own conclusions.

Other fascinating books concerning this era of American economic history include River of Shadows by Rebecca Solnit, Iron Empires by Michael Hiltzik, The Tycoons by Charles R. Morris and The House of Morgan by Ron Chernow.