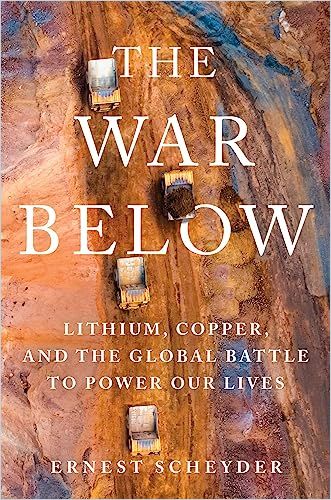

Reuter’s senior correspondent Ernest Scheyder presents the complex trade-offs that emission-reducing technologies create.

Not So Green

Reuter’s senior correspondent Ernest Scheyder looks into the metals and minerals that are making the green energy transition possible. He underscores the fact that electric-vehicle batteries and wind turbines may not be as green as you think.

“Rare Earths”

About 200 nations joined the Paris Climate Accords in 2016, in which they agreed to net-zero emissions by 2050. Achieving those targets means the end of fossil fuel reliance and a new era of renewable energy. Governments are focusing on cutting emissions from gasoline and diesel-burning vehicles, but that requires securing access to the minerals that go into rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, a crucial component of electric vehicles. By 2030, the global demand for lithium will soar by 40%.

Energy security used to be about crude oil and natural gas. Now it’s also about lithium, copper, and other EV metals.

Ernest Scheyder

Many consumer electronics and green energy solutions require rare earths, which consist of 17 different elements, including lanthanum, cerium, terbium, and neodymium. A single wind turbine need two or more metric tons of magnets, which require rare earths. Weapons producers such as Lockheed Martin use rare earths in everything from X-ray technologies to laser-guided missiles. Your iPhone vibrates because Apple manufactured its haptic engine using Chinese rare earths.Extracting and processing rare earths is costly and environmentally hazardous. The International Energy Agency estimates that the green energy transition will require 50 additional lithium mines, 17 or more cobalt mines, and 60 more nickel mines.

Dominating the rare-earth market grants China geopolitical power. Beijing has threatened to block the United States from importing Chinese rare earths, which could prevent defense contractors like Lockheed Martin from building American fighter jets.

Despite holding fewer than one-quarter of all the global lithium reserves, the United States will likely produce only about 3% of the lithium needed for the green energy transition by 2030. That’s partly because mining companies face “legitimate opposition” from environmentalists, Indigenous groups, and others who don’t want mines in their backyards polluting waterways, damaging habitats, and scarring the landscape.

Who wants to live next to a giant hole in the ground?

Ernest Scheyder

Just before leaving the White House, Donald Trump approved the construction of a Nevada lithium mine, Thacker Pass. When reviewing the mine proposal, the Nevada branch of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) cut corners and failed to properly assess the mine’s environmental impacts. The BLM ruled that the Lithium Americas company had “valid rights” to the area and was exempt from environmental regulations. Environmentalists, Indigenous groups, and cattle ranchers joined forces to oppose Thacker Pass. Despite the public outcry, courts ruled that Lithium Americas could begin excavation.

Economic and Energy Trade-Offs

Bolivia, which has the biggest share of the world’s lithium, with 19 million tonnes of untapped reserves, has faced similar adverse reactions. Under former president Evo Morales, Bolivia nationalized resources such as lithium and partnered with the German company ACI Systems to mine lithium and build an EV battery plant, but the deal fell through following resistance from Bolivian Indigenous leaders.The Bolivian government then entered into an agreement with the Chinese battery manufacturing giant CAT. To mine lithium, Bolivia must balance its economic incentive with the potential damage to its tourism industry and local ecology.

Without rare earths, there would be no wind turbines, no Teslas, and no F-35 fighter jets, among myriad other high-tech devices built using specialized magnets made from rare earths.Ernest Scheyder

In 2021, the Biden administration declared that half of all new light trucks and passenger cars on the market in the United States would be electric by 2030 — a goal set with buy-in from automobile makers General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. The administration hopes to invest in sustainable lithium mining called “direct lithium extraction” (DLE). Traditional lithium extraction involves evaporation ponds, which permanently drain all groundwater. DLE, though more costly, promises a minimally invasive, environmentally friendly solution.

If the United States could successfully extract lithium from California’s Salton Sea with DLE, that would mean less demand for lithium sourced via environmentally destructive practices in areas like Thacker Pass. According to one industry analyst, one-quarter of the global lithium supply could come from sustainable DLE processes, but only if innovators discover a DLE solution that works in practice.

Sacred Indigenous Lands

The motor of an EV contains more than a mile of copper wiring. Freeport-McMoRan owns Morenci in Arizona, the largest copper mine in North America; in 2022, it produced 900 million pounds of copper. Freeport-McMoRan cooperates with the San Carlos Apache and draws water from its land. But the tribe opposes a different mining project, Resolution Copper, led by Rio Tinto and BHP. Resolution Copper is being constructed in Oak Flat, which the tribe views as sacred land. Due to a controversial 2014 bill, the companies seized control of Oak Flat without the consent of the Apache.

Throughout the world, supplies of metal sit atop land considered sacred, or too special, or too ecologically sensitive to disturb. Whether these lands should be dug up in an attempt to defuse climate change is one of the defining questions of our time.

Ernest Scheyder

Americans and Canadians enjoy protections that prevents companies from damaging waterways with mining practices. For example, the Boundary Waters Treaty holds that neither the United States nor Canada can pollute the waterways that flow between the two countries. Environmentalists are using the treaty to fight a proposed nickel and copper mine near Minnesota’s Rainy River, which flows into Canada’s Hudson Bay. Proponents of domestic mines argue that when rich countries source minerals from poorer countries such as, for example, Zambia or the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the value chains in these nations involve exploitative labor practices and toxic pollution.

Tough Realities

Ernest Scheyder provides a behind-the-scenes tour of the ugly — and at times catastrophic —extraction of the materials on which EVs, wind turbines, and other non-oil burning technologies depend. A journalist, Scheyder writer clearly and doesn’t hesitate to express his outrage at environmental despoilers. His work proves especially valuable and revelatory because no one involved in for-profit green industries ever publicizes the true environmental cost of lessening fossil-fuel emissions damage. Scientists, policymakers, students, consumers, and businesspeople will learn much from Scheyder’s research.