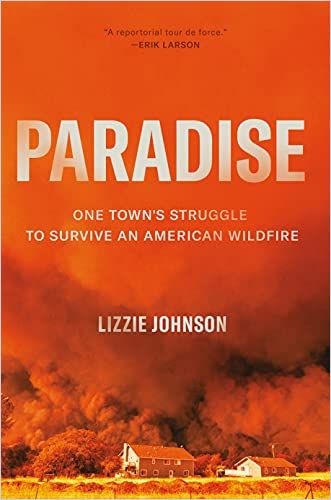

Washington Post reporter Lizzie Johnson provides a detailed, heartbreaking account of the 2018 Paradise fire that destroyed a California town.

Negligence, Confusion, Death

Washington Post reporter Lizzie Johnson recounts how 52,000 residents of Butte County, California awoke on November 8, 2018 to what seemed an ordinary day, and by nightfall, saw their lives go up in flames. Johnson chronicles the fast-moving wildfire and the one-road town it demolished, while offering valuable advice for anticipating, preventing, minimizing, responding to and recovering from crisis.

They couldn’t fight it. The inferno was too big, too fast. Lizzie Johnson

Amidst a slew of Paradise fire books, some by outside observers and some by townspeople, Johnson’s stands out for its rigor, in-depth reporting, humane perspective, and hard-earned knowledge of fires and their consequences. Johnson’s telling, illuminating portraits of many of the people involved pull you directly into the inferno.

The 2018 Northern California Camp Fire

Johnson recounts that at 6:15 a.m. that day, the wind blew a Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) transmission line off a tower in northern California’s Butte County, igniting a fire. By 6:30 a.m., the state fire agency, Cal Fire, dispatched a local firefighting crew to control it. At 6:44 a.m., the crew reported the blaze could become a major fire.

The fire rapidly expanded toward Paradise, California and its 26,500 residents. Evacuation orders started around 8 a.m., but narrow exit routes created traffic jams.

Local fire departments joined Cal Fire to try to suppress the blaze, but, as Johnson tells dramatically, its speed and intensity overwhelmed them. Responders switched to saving lives, not property. A bus carrying school children got stuck in the traffic jam as stalled, burning and abandoned vehicles blocked evacuation routes.

Across the utility’s entire transmission system, it had found a pattern of inadequate inspection and botched maintenance.Lizzie Johnson

The Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise in four hours and killed 85 people. Another 50 died of related causes. The fire displaced more than 52,000 people and caused billions of dollars in losses. Ultimately – and extraordinarily – Johnson reveals, PG&E pleaded guilty to 84 counts of manslaughter in an unprecedented admission of corporate criminal liability.

PG&E

As Johnson explains, while functioning as a de facto monopoly, PG&E enjoyed a cozy relationship with its oversight agency, the California Public Utilities Commission (PUC).

Johnson cites a December 2019, voluminous PUC report citing the “catastrophic negligence” that led to the fire. Regulations called for inspection of PG&E’s towers every five years, but no one had inspected the tower at fault for 17 years. Johnson puts the cost of the component of its machinery that failed at $19.

She found that decades of fire suppression and recent insect attacks created millions of acres of tinderbox forests. Climate change generated high temperatures, drought, erratic rainfall, early loss of snowpack and unusual lightning. Johnson adds that no substantial rain had fallen for seven months and that the day of the fire featured a high-pressure system and gale-force winds.

Any of these signs would be troubling on its own…Combined, they foretold an unprecedented peril. Lizzie Johnson

Paradise’s haphazard urban planning led to abundant sprawl and, as Johnson learned, drug abuse and limited resources eroded the community, where Social Security checks provided the main source of income. Ignoring warnings about impeding evacuation routes, the town narrowed its road from four lanes to two in order to reduce traffic accidents.

Disaster Planning

Johnson reports that surviving more than 100 fires in the Sierra Nevada foothills over the previous 25 years gave Paradise a sense of invulnerability.

Eighty-two percent of Paradise residents never received an emergency alert. Lizzie Johnson

Cal Fire seldom enforced its requirement that people clear 100 feet of flammable material from around their homes. The town government held an evacuation drill in 2016, but, Johnson laments, only 70 people showed up.

Disaster response consists, Johnson found, of three phases: denial, deliberation and action. A responder’s job is to move – and help others move – quickly out of the first two phases and into the third.

In the Camp Fire, authorities assured residents they were not in trouble. Then, when the fire drew near, residents wasted valuable time calling other people, waiting for evacuation orders, and checking social media rather than moving toward safety.

Even after evacuation orders, some people, especially the elderly, didn’t move, thinking, Johnson surmises, that they were somehow immune. Others got stuck in traffic, and died. People blindly poured into evacuation routes without considering alternative roadways, and they stopped at red lights. Others abandoned their cars in traffic and took their keys, blocking escape routes.

Johnson explains that law enforcement officers and firefighters communicated on separate channels. Cellphone service breakdowns created delays for firefighters and by the end of the day, 17 damaged cellphone towers went offline.

The uncoordinated alerts were scattershot. Lizzie Johnson

Eventually a Highway Patrol pilot called out traffic bottlenecks from his plane, relieving lethal congestion. Johnson uses the pilot’s perspective as her most potent metaphor: In the midst of challenges, she says, step back and consider the big picture. PG&E ended up paying $13.5 billion into a trust fund for Camp Fire victims, along with $25 billion in settlements. Johnson faults local officials for not ensuring residents could evacuate safely and efficiently.

Illuminating Reportage

Johnson is a newspaper reporter; writing on a grand scale for the first time might have daunted her. But she proves more than up to the task, moving from intensely personal stories of survivors to the grand tactics of firefighting to the grim aftermath and the legal consequences. Johnson’s adept at evoking these different universes and tying them together into a cogent whole.

The Town Council never designed a system for emptying the entire ridge at once. Lizzie Johnson

She doesn’t over-dramatize the incredible drama and doesn’t hide her outrage at PG&E’s negligence or the town’s resistant foolishness. Johnson provides a vivid, evocative saga and a dire warning worth heeding.

Other books on the Paradise fire include Fire in Paradise by Dani Anguino and Alastair Gee; Paradise Lost by James W. Lee; I Escaped the California Camp Fire by Scott Peters and S.D. Brown; and Voices of Paradise by Maria Elizabeth Rosales and Eden Davis.