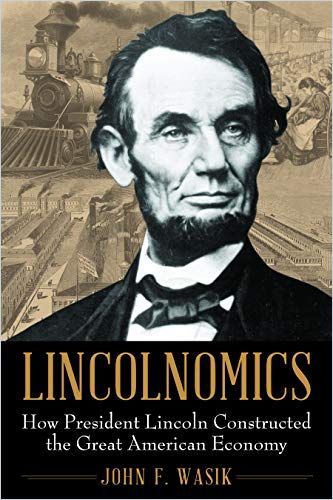

Abraham Lincoln was an economic and infrastructure visionary, according to this well-researched and surprising historical account.

Lincoln’s Practical Ideals

History remembers Abraham Lincoln as the Great Emancipator. But his legacy goes far beyond waging and winning the Civil War, prolific author John F. Wasik asserts in this intriguing study. Wasik presents Lincoln as the architect of a populist and progressive economic platform – “Lincolnomics” – that championed a central currency, a national banking system and public investment in economic development. Wasik argues that, while Lincoln’s financial initiatives were far from perfect, they represent a significant, overlooked part of the president’s contribution to the American republic.

Equality

Lincoln, Wasik explains, thought the US economy advantaged the few and disadvantaged the many. Lincoln advocated for more opportunities to all. He valued public investment in education and innovation, as well as a strong federal government – all radical ideas during his time.

As a moral policy leviathan, Lincoln reshaped the world.John F. Wasik

Lincolnomics held that greater equality and investment in education and transportation would unlock growth.

Infrastructure

As an attorney, Lincoln took on an insurance dispute involving the owner of a steamboat that had crashed into a bridge on the Mississippi River near Davenport, Iowa. The boat’s owner alleged the bridge was a navigation hazard. Lincoln had litigated railroad cases and argued that rail routes and bridges were crucial to America’s economic future. The trial ended in a hung jury, but new bridges across the Mississippi helped the US economy transform from one of small-time farmers to a network of producers and consumers.

The profusion of infrastructural developments threatened the plantation-based Southern economy.John F. Wasik

Democrats and Southerners in general opposed taxpayer investment in economic development. Lincoln argued that local initiatives such as a canal near Chicago benefited the entire nation by linking trade from New York City to New Orleans. This view faced staunch resistance; prior to the Civil War, presidential vetoes had stopped many public infrastructure projects.

The Civil War

As the Civil War began, Lincoln understood the importance of innovation: He toured naval yards to inspect new weapons and ships. He grasped how infrastructure affected military strategy and congratulated General Ulysses S. Grant on the capture of Vicksburg, a crucial transit point.

Economic progress was the solid ballast of public higher education, but it was on a small, slowly sailing ship.John F. Wasik

Lincoln supported investing in public education through a system of land-grant universities, though Wasik is careful to underscore that women, Native Americans and Black Americans wouldn’t gain access to land-grant colleges for decades. Government snatched the land that housed new public universities from Native Americans.

The Pacific Railroad Act

The first railroad law, signed by Lincoln in 1862, established rights of way and authorized government bonds for railway expansion from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Laying the foundation for a cross-continental railroad, Lincolnomics ushered in America’s industrial revolution.

At the height of the Civil War, Lincoln’s pen was poised to reshape the country far beyond the reach of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address.John F. Wasik

Demonstrating his refusal to be an expansionist cheerleader, the author points out that America’s robber barons proved the primary beneficiaries of the rail project, undercutting Lincoln’s wish for greater economic equality. Nonetheless, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Indianapolis and Pittsburgh became manufacturing boomtowns and, on the remote Great Plains, consumers were able to order mass-produced goods for rail delivery.

The Homestead Act

Lincolnomics sought to redistribute wealth to the poor and middle classes. In 1862, the Homestead Act promised 160 acres to anyone who paid a $12 registration fee and who stayed on their land for five years.

The post-Civil War laissez-faire environment led to rapacious profiteering and speculation.John F. Wasik

The Homestead Act remade the US economy for millions, though it stole Native American land and offered it only to white Americans.

Taxation and a Centralized Currency

Wasik details how American money had long been a hodgepodge of state-issued scrips. Lincoln oversaw the creation of the greenback as the new national currency. The Civil War also exposed the financial reality that the government had little revenue, but it needed to spend heavily to build a war machine.

Examiners of the Civil War years’ impact habitually miss that some proto-progressive legislation emerged under the conflict’s shadow.John F. Wasik

Lincoln signed the Revenue Act, which authorized a 3% tax on earnings. Congress changed the rate to apply only to annual earnings of $600 to $10,000, and it mandated a 5% tax rate on incomes over $10,000. Tax revenues funded America’s war effort, and the economy boomed.

The Interstate Highway System

In 1919, Dwight D. Eisenhower’s military convoy took 62 days to cross America over poorly constructed and maintained roads. During World War II, Eisenhower realized America needed something similar to Germany’s autobahn.

Lincoln was never far from Ike’s mind…, particularly as he rested in his farm home adjacent to the Gettysburg battlefield.John F. Wasik

Until the 1950s, only state and local governments built or maintained roads. Despite opposition, President Eisenhower kicked off the interstate highway age – a public investment that irrefutably spurred economic development in the United States.

Lincoln’s Ideals

The Republican Party, Wasik insists, has turned away from Lincolnomics. He thinks Lincoln would have approved of Teddy Roosevelt’s progressivism, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Dwight Eisenhower’s infrastructure investments.

The American Dream has been routinely denied to people of color.John F. Wasik

Modern Lincolnomics, Wasik believes, would embrace living wages for workers, an equitable tax system, funding for public schools, and equality in voting rights, law enforcement and economic mobility.

Review

Wasik is correct in asserting that few Americans are likely aware of Lincoln’s economic policies and their historic legacies. So he provides both a historical and political record-correction that proves immensely readable and informative. Wasik shows little patience for current conservative policies, casting himself as a modern-day Lincolnite and projecting Lincoln’s pragmatic, hard-nosed approach to contemporary problems. This is an unexpectedly intelligent, in-depth and revealing work – the best sort of history.

John F. Wasik also wrote The Investment Club Book, Keynes’s Way to Wealth, The Cul-De-Sac Syndrome and Lightning Strikes, among other titles.