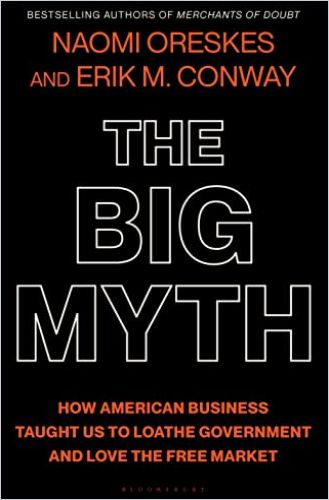

Professors Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway trace the origins of the talking points that have come to characterize laissez-faire economics.

Laissez-faire Origins

In this intriguing historical study, Naomi Oreskes — the Henry Charles Lea Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University — and Erik M. Conway, the historian for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, trace the US origins of laissez-faire economics.

Capitalism

Capitalism has long privatized profits and socialized costs. In 1900, one in 1,000 workers across all industries died on the job. In one dramatic example, some 6% of all Pennsylvania coal miners died annually. A worker in Scranton, Pennsylvania’s anthracite mines had a greater than 50% chance of dying or suffering a severe injury on the job. But employers suffered no repercussions, and a dead worker’s spouse and children received no compensation.

Reform emerged during the Progressive Era of the early 1900s in the United States. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt proposed that America institute a workers’ compensation program. Other reforms included better working conditions, limits on child labor, the five-day workweek, and workers’ collective bargaining rights.

Late 19th-century American capitalism was a deadly affair. Every year, thousands were injured, maimed or killed in the course of their daily work.Naomi Oreskes, Erik M. Conway

Corporate leaders argued for business owners’ freedom to run their companies as they liked, and for the rights of parents to decide if and when their children worked.

The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) formed in 1895 to lobby on behalf of its members. NAM favored protectionism and opposed unions, federal taxes, and limits on child labor. NAM claimed that anyone advocating for child labor restrictions was a communist. Henceforth, hard-core capitalists would paint regulation as an attack on freedom and American business.

In the early 1920s, as NAM unleashed a propaganda war over child labor, the National Electric Light Association (NELA) painted private, for-profit electricity as good and municipally provided power as bad. From 1921 to 1927, US newspapers published nearly 13,000 opinion pieces claiming that public utilities served “Bolsheviks” and “Reds.” NELA is today the Edison Electric Institute, and it denies climate change. Other industries have adopted NELA’s tactics of bullying and disinformation over the decades.

The United States stock market collapsed in 1929. Overproduction and dwindling consumer spending caused a deflationary spiral and a depression ensued.

The theme of (American) individualism versus (anti-American) collectivism would run steadily through corporate critiques of the New Deal.Naomi Oreskes, Erik M. Conway

President Franklin D. Roosevelt ushered in assertive regulation, and opponents fought back. The Edison Electric Institute, for example, sued the government-owned and -operated Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) dozens of times, going to the Supreme Court three times; the TVA won all three cases.

NAM Dogma

In the 1930s, business leaders invented a gospel of economic individualism. NAM advocated employers’ freedom from unionization and taxation. NAM characterized the public sector as “extravagant,” “wasteful,” and “flagrant,” and said the private sector granted “prosperity” and “progress.” NAM conflated free enterprise with the Founders’ wishes, but neither the Constitution nor the Declaration of Independence mention any such thing.

The right wing argued that any policy that didn’t embrace a free-market ethos was Stalinism. NAM and its allies successfully cast the New Deal and Keynesian economic policies as socialism.Free marketers had to square their ideology with Christianity; after all, Jesus unapologetically urged charity and criticized the rich.Over the decades, Christian laissez-faire proponents held that the pursuit of wealth was godly, income inequality was natural, and unions were evil and corrupt.

In the 1930s and 1940s, famed director John Ford criticized capitalism in his film Stagecoach, with a villain banker who uttered laissez-faire talking points. In John Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath, Depression-era hero Tom Joad railed against anti-union corporations. In How Green Was My Valley, Ford depicted coal mining as a destructive force and unions as a salvation. The House Un-American Activities Committee asserted that Steinbeck’s and Ford’s works were Stalinist propaganda. The president of the Motion Picture Association of America told screenwriters in 1946, “We’ll have no more Grapes of Wrath.”

Ayn Rand, a native of Russia, hated communism because the Russian Revolution had led to the loss of her family’s fortune. In 1943, Rand published The Fountainhead and sold the film rights to Warner Brothers. By 1947, Rand was coaching screenwriters to avoid anti-Americanism. In a Motion Picture Association pamphlet, Rand wrote “Don’t smear the free enterprise system” and “Don’t smear industrialists.” The FBI even investigated the movie It’s a Wonderful Life as subversive amid the anticommunist craze.

The University of Chicago

The University of Chicago would become synonymous with market fundamentalism, hiring neoliberalists Milton Friedman and George Stigler. Friedman wrote the foundational Capitalism and Freedom in 1962.

In contrast to the American founding fathers, who put life before liberty, Friedman’s radical individualism puts liberty before life.Naomi Oreskes, Erik M. Conway

Robert Bork, a University of Chicago graduate and rejected candidate for the US Supreme Court, held that monopolies resulted from normal competition. Bork’s argument undermined decades of consumer protections. In 1980, Ronald Reagan kicked off his term with a speech that could have been written by NAM and NELA: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Review

Naomi Orestes and Erik M. Conway reveal the hidden history of right-wing, pro-business rhetoric and its profound effect on economics and politics in the 20th and 21st centuries. They describe how tropes about the profligacy of government and the virtue of the private sector became deeply ingrained in US politics. The authors make a convincing case that this rhetoric is such a part of the American political landscape that few people wonder about its origins. Orestes and Conway make clear that, well before Ronald Reagan, Milton Friedman, or Ayn Rand, little-remembered trade and special interest groups polished and perfected their arguments in favor of free markets to right-wing acclaim. History and economics students, economists, and citizens curious about the entwining of politics, money, and propaganda will find this a fascinating read.