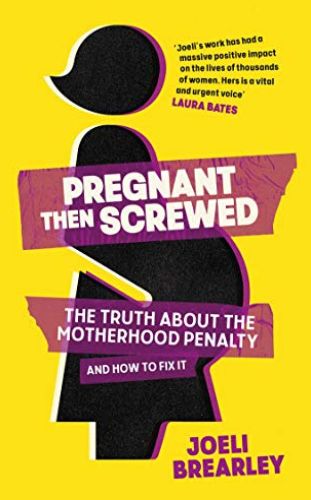

Women pay a professional and financial price for having children – in employment opportunities, career advancement and salary. In this infuriating, compassionate book, a British women’s rights activist describes exactly how the workplace fails women with children, what women can do to fight back, and how society can start loving its mothers.

Justice for Mothers

In the United States, women earn, on average, approximately 80% of what men do. And women in every country in Europe, too, receive lower average salaries than their male counterparts – an average of 13% lower across the EU in 2020, according to the European Commission.

But it seems statements about the gender pay gap need to carry a startling, heartbreaking qualification: Women who don’t have children earn about the same amount as men. The pay gap arises because women who have children earn far less than women who don’t – a phenomenon sociologists have dubbed “the motherhood penalty.” Author Joeli Brearley also terms it “the procreation gap”: the literal price women pay for perpetuating the human race.

The Procreation Gap

Brearley lays out the reasons for the procreation gap with passion, clarity and more than a few swear words. And she brings the receipts. First, she notes, women face rampant employment discrimination during pregnancy and motherhood. In the United Kingdom alone, 54,000 women lose their jobs each year just for clocking in pregnant, and nearly 80% of working mothers contend with discrimination or negative treatment at work.

From the moment the stick turns blue, we face challenges and barriers we never previously knew existed.Joeli Brearley

Women do have the right to 39 weeks of paid maternity leave in the United Kingdom, and in 2010, the UK’s Equality Act outlawed discrimination on the basis of maternity or pregnancy. But as Brearley points out, legal rights mean little when employers regularly disregard them – leaving little recourse for women who are already exhausted by childbirth and the travails of mothering an infant. A mere 1% of British women who encounter workplace discrimination related to maternity or pregnancy ever undertake legal action. Yet 77% of working mothers report having experienced some form of workplace discrimination. Young mothers, those with disabilities and minority women face additional challenges.

Get Pregnant, Get a Pink Slip

In 2013, while working for a children’s charity, Brearley received a phone call from the organization’s CEO informing her that her contract had been terminated. Brearley had told her employer that she was pregnant only the day before.

Brearley first sought to bring a suit against the employer, but the combination of legal fees – estimated at £9,000 (about US$10,700) – and a risky pregnancy led her to abandon the case. Women have only three months from the date of the discriminatory action to start proceedings, Brearley explains, a limitation that would have pregnant women, already struggling with financial worries due to the loss of income, also take on the expense and stress of raising a tribunal claim.

No matter how much we try to escape traditional gendered roles…women are constantly being nudged back to the kitchen sink.Joeli Brearley

Brearley soon found new employment. But as she spoke with other mothers, she learned her experience was far from isolated. She founded the nonprofit organization Pregnant Then Screwed in 2015 to support women who’ve suffered discrimination on the basis of their pregnancy or maternity and, ultimately, to end the motherhood penalty. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she took the British government to court for indirect sex discrimination – and won. Brearley serves on a UN working group for women’s human rights, and in 2021, Vogue listed her among the 25 most influential British women.

Guidance for Mothers

Throughout the book, Brearley offers heartfelt advice and practical knowledge to help mothers navigate – and fight back against – a work world that systematically excludes and disadvantages them. Noting that women often fail to take action because guilt and shame hamper their response, Brearley explains where those feelings of guilt and shame stem from societal expectations, inaccurate media portrayals of motherhood, gender-biased scientific studies and denigrating messages from employers themselves, and she encourages women to protect their mental health and assert their rights.

Pregnant Then Screwed has supported thousands of women in insisting on their rights in the workplace, and that extensive experience informs Brearley’s advice to readers who might be undergoing their own difficulties. For example, Brearley points out that many employers weaponize nondisclosure agreements to gag and disempower women who’ve suffered discrimination. She assures readers that these agreements rarely provide legal cover for wrongdoing – and that employers know this.

A Better World for Mothers

After thoroughly defining the problem – the persistent pay gap for mothers; the discrimination women face just for having children; and the challenges and burdens placed on the shoulders of women who become pregnant, bear children or lose them – Brearley outlines solutions with equal precision. She dismisses self-employment as a solution, citing sobering facts: Some 60% of new businesses fail within their first three years; about half of all self-employed people subsist on poverty wages; self-employed mothers often can’t afford to stop working after giving birth; and the gender pay gap stands at a stunning 43% among the self-employed.

We’ve forced our childbearing hips into pairs of corporate trousers that were never designed for us, and, quite frankly, it has given us thrush.

Instead, Brearley calls for specific reforms in a host of areas: flexible working hours for everyone (and fewer hours in the first place); accessible, affordable, high-quality child care; higher salaries for child care workers; a shift to a focus on productivity rather than presenteeism; paternity leave, paid and ring-fenced so fathers can actually spend more time with their children; a justice system that provides access for pregnant and post-partum mothers, and that holds companies accountable; and quotas – such as those already in existence in France, Italy, Germany, Spain, China and India – that ensure women hold a measure of power in corporations.

Although Brearley’s anecdotes and case studies focus on the United Kingdom, her passionate arguments deal with universal themes and problems. If you are a mother or if you have a mother, Brearley’s treatise will likely enrage you. She makes a powerful case that it’s time to stop penalizing women for procreating, and to start building a society that supports mothers.