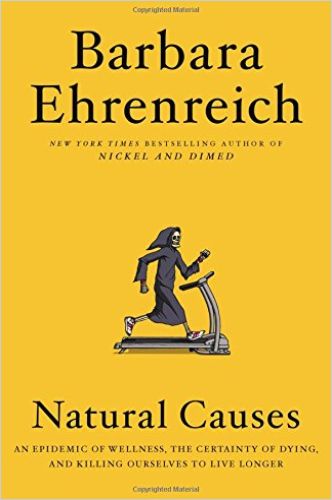

Award-winning journalist and best-selling author Barbara Ehrenreich offers her stringent views of current American society and its discontents.

“I’m Against It”

Investigative journalist and best-selling author Barbara Ehrenreich holds a PhD in cellular immunology from Rockefeller University and has written 12 books, including the New York Times bestseller Nickel and Dimed. Here she entwines her experiences in science and medicine with thoughts on trends on fitness, nutrition, mindfulness and the quest for longer life. Ehrenreich’s singular take on medicine and science means she questions doctors’ recommendations and whether they practice evidence-based science, and she doesn’t do preventive screenings. She offers screeds about gym culture, smoking, drinking, religion and spirituality.

Ehrenreich balances on a tightrope between complaining and offering astute insights – that turn out to be double-edged swords – into American health and fitness processes. At times – as when she seems to regard fitness as ultimately pointless because you’re going to die anyway – you may wonder whether she denies joy for its own sake or is exaggerating her feelings to make an editorial point. As an award-winning journalist, Ehrenreich has in the past brought less ambiguous and more subtle viewpoints to her subjects.

The Guardian, among other outlets, had no ambivalence about Natural Causes: “This book is joyous. It is neither anti-medicine nor anti-prevention; it is pro-balance, pro-skepticism and pro-perspective.” And The New York Times said, “She sits in contemplation of death itself in the book’s concluding, very beautiful passages, bringing to it her characteristic curiosity and awe at the natural world.” Ehrenreich’s concluding passages prove quite moving, though some readers may disagree with The Guardian assessment of her as “pro-balance.”

Routine Health Care Screenings

Presenting herself as a skeptic regarding United States’ medical practices, Ehrenreich discusses receiving a diagnosis of the bone degeneration syndrome, osteopenia. The drug doctors then often prescribed for osteopenia, she reveals, could have caused further bone degeneration and fractures. The author’s outrage at this cozy circle of corruption provides a launching pad for her well-aimed, appropriate vitriol against medicine in America.

A cynic might conclude that preventive medicine exists to transform people into raw material for a profit-hungry medical-industrial complex. Barbara Ehrenreich

Ehrenreich reminds readers that US doctors, hospitals and drug manufacturers profit from ordering tests in hopes of finding something wrong, which, with sufficient testing, she notes, they inevitably will.

The author regards many medical rituals as violations of personal space, but cites doctors saying patients get upset if they don’t perform the ritual of a physical exam. She notes that rituals involving touch provide a placebo effect. Ehrenreich concludes that even a sham of caring may be all people need.

Physical Fitness

Ehrenreich has little use for working out. She finds gym owners exploitative and gym members credulous. Her arguments maintain that people exercise because if they can’t change the world or upgrade their career, they can at least change their bodies. This seems a gross oversimplification.

Working out very much resembles work, or a curious blend of physical labor and office work. Barbara Ehrenreich

The shallowness of some of her positions are cast in stark relief by her attempts to view exercise so reductively. Ehrenreich does offer the insight that gyms are a society, with a society’s codes and morals.

Mindfulness

Ehrenreich argues that mindfulness – which she regards as hokum – replaces a past generation’s “positive thinking.” She cites a 2014 “meta-analysis” of meditation programs that recognized their effectiveness at reducing stress, but no more so than muscle relaxation, medication or psychotherapy. The author finds those vested in mindfulness to be vain and self-satisfied. This aligns with much of her book, which examines how Americans delude themselves in the face of societal, economic and political dissatisfactions far beyond their control.

Life Expectancy

Ehrenreich finds an appropriate target for her wrath when she calls out how the wealthy eat right and exercise, but poor Americans struggle because unhealthy food is cheap. The rich wonder why blue-collar workers “don’t take better care of themselves” as those workers suffer limited upper mobility.

The author notes that in 2011, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) declared opioid addiction an “epidemic” whose victims were mostly white. She details the United States’ high infant mortality rate and the wide gap in health status between wealthier and lower-class Americans, which race and other factors compound.

Pressure

Ehrenreich rails against the social pressure on seniors to stay young by exercising and eating right. She recognizes that aging brings decreased ambition, competitiveness and lust while spawning vision loss, menopause, lower bone density, knee and back pain, etc. She addresses the American addiction to perpetual youth and how that negatively affects the aging’s self-image.

The Self

Most people accept the idea of a “soul” or spirit that doesn’t die, but, the author hastens to point out – somewhat obviously – that no one has proved its existence. Contemporary secularism uses the language of religion, urging people to “believe,” “love” and feel “esteem” about themselves. Ehrenreich finds this ridiculous.

It is one thing to die into a dead world and, metaphorically speaking, leave one’s bones to bleach on a desert lit only by a dying star. It is another thing to die into the actual world, which seethes with life, with agency other than our own, and, at the very least, with endless possibility.Barbara Ehrenreich

While people with spiritual or religious beliefs consider the afterlife, Ehrenreich takes bitter amusement from the secular spending their last days trying to make their mark on the world. She regards this mark as fleeting, indeed.

Live!

Ehrenreich condemns many practices, some worthy of her outrage, some so harmless as to seem flyspecks in the spiritual/psychological world. Though she assaults all manner of self-soothing behavior, her constant theme is that you have one life to live and it’s short, so you better vest in as much common sense and self-protection as you can. Some of the book feels like essays that never quite reach their point, but, throughout, Ehrenreich offers elegant, beautiful sentences that linger in the mind long after her somewhat inexplicable crankiness dissipates.

Whether you enjoy her insights or they irritate you profoundly, Ehrenreich’s brilliance remains undimmed in her Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America or her essay collection Had I Known.