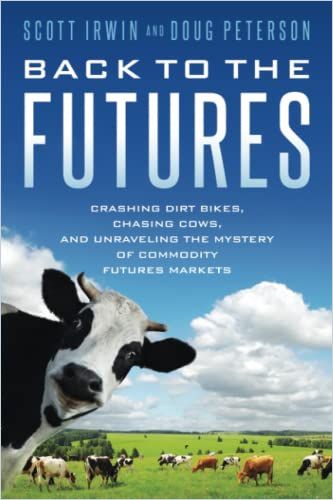

Scott Irwin, the chair of agricultural marketing at the University of Illinois, disarmingly details the history, functions, and dysfunctions of agricultural futures markets.

How Futures Function

The Laurence J. Norton Chair of Agricultural Marketing at the University of Illinois, Scott Irwin — with writer Doug Peterson — details the movements and effects of commodity futures markets.

Transferring Risk

US commodity markets blossomed when growers of wheat and corn moved onto the American Plains in the 1830s and 1840s. When a winter freeze of rivers and roads prevented farmers from delivering autumn harvests, they had to wait until spring to get their crops to market. If every farmer across the Plains followed suit, all would deliver their produce at the same time, flooding the market and collapsing prices. The Chicago Board of Trade began selling forward contracts in 1851. For example, a grain elevator operator could lock in profit by agreeing to sell corn at a guaranteed price in a few months.

Speculators take enormous risks, thereby reducing the risk on farmers and middle operators, such as those who run the storage elevators or process grain.

Scott Irwin, Doug Peterson

Commodity markets perform a valuable risk management function. By concentrating risk in one place, these markets enable fortunes to be made or lost in moments. Some regard speculation as legalized stealing, but Irwin insists that overregulation of futures markets never works out.

Hedging, which parallels buying an insurance policy, is the opposite of speculating. Farmers who want to protect themselves from price fluctuations use futures contracts as side bets against unexpected dips in crop prices. If, for example, a corn farmer produces 5,000 bushels of corn, he or she might sell the produce for cash in October at $3.50 a bushel, for a total of $17,500. The farmer could hedge thusly: In May, using a futures contract, the farmer offers to sell 5,000 bushels at $5 per bushel, or $25,000. By October, prices have fallen to $4 per bushel, or $20,000, netting the farmer a $5,000 profit. The farmer sells the actual 5,000 bushels at $3.50, for $17,500, and collects the $5,000 payout from the hedge.

If corn prices have soared by October, the farmer does well at market, but the loss on the futures contract offsets any profits. If prices plunge, the futures contract softens the blow. Producers who employ hedging strategies reduce their profits in good years while saving themselves from financial ruin in bad years. The textbook hedging strategy calls for producers to hedge all their product for a year, but most farmers opt for partial hedging strategies.

Beat the Market

When Scott Irwin joined the faculty of the University of Illinois, he and a colleague launched the Agricultural Market Advisory Service Project. They rated the picks of 25 market gurus selling advice to commodities traders and farmers. Irwin and his research partner made hypothetical trades based on their advice. Only one of the 25 advisers consistently beat the market.

The experience convinced Irwin that few traders can beat the market and that only those with strong information succeed.

Agribusiness titan Monsanto long claimed that its genetically modified organisms (GMOs) brought huge increases in crop yields. Irwin teamed with meteorology graduate student Mike Tannura to analyze rising crop yields. Tannura found that near-perfect growing conditions drove explosive corn yields, not GMOs.

I have spent much of my career defending the value of commodity futures markets and arguing for the importance of speculators in keeping the market running smoothly.

Scott Irwin, Doug Peterson

After Tannura earned his degree in agricultural economics, he launched a weather forecasting service in Chicago. Tannura, Irwin, and another Illinois professor developed a service that forecasts crop yields for corn and soybeans. These forecasts help farmers understand how to hedge their positions.

In the Great Russian Grain Robbery of 1972, the Soviet Union experienced crop failures and bought grain from US farmers. Large grain companies found out about the USSR’s purchase plans before the rest of the market and bought up as much grain as they could. When farmers who had sold early realized they had been taken, they were livid. So were members of Congress, who directed the US Department of Agriculture to require disclosures of large transactions by grain companies, a safeguard that still exists.

Cattle

In the 2000s, amid rising prices for oil, corn, and other basic commodities, some in Congress and the media called for a crackdown on futures markets.

Irwin defended futures markets, testifying before Congress and co-authoring an op-ed in The New York Times. He argued that rampant speculation was not to blame for rising prices. The most intense speculation occurred in livestock and meat futures markets — but livestock and meat didn’t experience soaring prices. Conversely, prices were high for products that didn’t have futures markets, such as edible beans.

In 2019, the Corn Belt experienced a historically wet spring. Farmers delayed planting; Irwin advised farmers to leave part of their fields fallow to collect crop insurance. Irwin expected Illinois farmers to keep three million to four million of their 12 million acres out of production, thus reducing supply and boosting prices later in the summer. But farmers kept only one million acres out of production. Irwin bet on rising prices, and lost.

It is a strange paradox that the efficiency of commodity futures markets depends on enough people believing it is not perfectly efficient to keep them collecting information and trading on it.

Scott Irwin, Doug Peterson

For a market to function efficiently, a subset of traders must believe it’s possible to outperform the market. As a farmer, Irwin knows that traders, like cattle, follow the herd. But few can predict where the herd will go.

For Experts and Beginners

Irwin achieves the almost-miraculous task of conveying arcane information in a clear, folksy way. Irwin’s primary message is that futures markets might be unruly, but they perform a valuable service in tamping down volatility in the prices of food and energy. He explains this world primarily for non-experts, though Irwin’s decades of investigation, research, and a distrustful view of markets mean that experienced professionals can learn much from him. As for newbies, accessing Irwin’s knowledge and advice demands a fairly complex understanding of futures math and a determination to follow each example through to the lesson that appends it. For those launching a career in futures markets or commodities hedging, Irwin offers a foundational, irreplaceable guide. He delivers his anecdotes, personal experiences, historical examples, and amusing tales with wit, fondness, and a keen analytical eye.