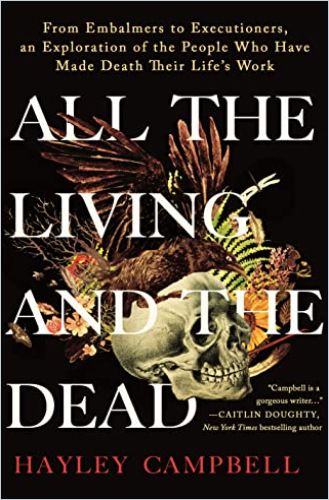

London broadcaster and journalist Hayley Campbell dissects the processes of taking care of the dead.

Bring Out the Dead

Author Hayley Campbell, a broadcaster and journalist based in London, explains that embalmers, executioners, funeral directors, gravediggers, and cremators take on tasks that mourning families outsource. She spends time with them and reports tellingly on their work.

Dead Bodies

Neal Smither of Crime Scene Cleaners, Inc. has cleaned crime scenes for more than 20 years. The houses of crime scenes sell more easily after Smither erases all traces of violence. Half a million people follow his before-and-after crime scene photos on Instagram. Smither resents customers who have less interest in the person who has died than they do in the deceased’s belongings.

Terry Regnier, director of anatomical services at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, works with cadavers – bodies donated for Mayo’s scientific research. He shaves the heads of the dead, which makes them easier to study and “less recognizable.” A machine fills the vascular system of each body with embalming fluid, alcohol mixed with the preservative formalin, the disinfectant phenol, and the moisturizer glycerine.

Nick Reynolds, the only commercial producer of death masks in the United Kingdom, doesn’t ask people why they want what he makes. Death masks go back to ancient times, and despite modern photography, the market for them endures.

When people die, their faces relax into a serene expression due to the release of tension and pain, Reynolds says. He has made casts of the face of a 14-year-old cancer victim and the feet of a premature baby. To make a mask, Reynolds pours blue alginate on the face, lets it set, and applies plaster bandages to form a hard cast, which takes 20 minutes. He regards mask-making as a grim personal duty, but he has no preoccupation with death.

The Kenyon company, near England’s Heathrow Airport, has provided international disaster relief services for more than 100 years. It works with government authorities to respond to aircraft and train crashes and serves airlines, railroads, and oil and gas producers. Kenyon sets up emergency phone numbers to report missing persons and refer people to family assistance centers. It updates disaster responses and arranges travel for affected families.

The death machine works because each cog focuses on their one patch.

Hayley Campbell

Kenyon handles post-disaster recovery of the deceased’s belongings. In 2017, a tragic fire at the Grenfell Tower in west London killed 72 people and injured 70 others. Two years later, Kenyon was still engaged in the process of cleaning and returning the remnants of 750,000 personal possessions recovered from the burned building.

Mark Oliver, VP of operations at Kenyon since 2018, never denies a family’s request to see a relative’s body. He advises them when it is unfit for viewing or is only a fragment, but lets the family make the ultimate decision. Without seeing the dead body or, at least, part of it, Oliver has learned, families can stay in “limbo” – unable to accept the reality of their loss.

Executions

In 2017, the state of Arkansas planned to execute eight prisoners over an 11-day period, hurrying to meet the “use by” date on a fatal injection drug, midazolam. A group of 23 former death row employees protested. They cited the traumatic impact such a compressed execution schedule would have on the staff.

Now I see all of it: death shows us what is buried in the living.

Hayley Campbell

Jerry Givens, now in his 60s, was the only person among the protestors with the job title, “executioner.” In 1974, he started working as a corrections officer at a Virginia penitentiary. At the time, no state in America imposed the death penalty. In 1977, Givens joined the prison’s anonymous nine-man execution team. Givens never told his wife about his special duties until after he left the team.

Of the 113 executions in Virginia since capital punishment resumed, Givens has performed 62 of them, 37 by lethal injection and 25 by electric chair. Givens pushed the button that activated the chair or delivered the lethal injection. A religious man, he believes an afterlife awaits the prisoners, and that death is a beginning, not an end.

Preservation

Dead bodies decay at different rates in a process that begins with the self-destruction of cells deprived of oxygen. Within four hours of death, reduced body temperature launches rigor mortis, and after 12 hours, the body is stiff. After 48 hours, the stiffness dissipates, and putrefaction begins.

As part of preparing and preserving a body, embalmers wash the deceased’s hair, place convex pieces of plastic under his or her eyelids, and wire the jaw shut. Intravenous embalming fluid adds plumpness to the skin as the veins turn pink, conveying the image of warmth.

Death is not a moment but a process. Something fails in the body and the system shuts down as the news spreads.

Hayley Campbell

A standard autopsy takes about an hour. Some anatomical pathology technologists (APTs) report they suffer less emotional trauma working on bodies that are cold than they experience working on the newly dead.

Robert Ettinger, author of The Prospect of Immortality, suggested freezing the dead and protecting their bodies from decay until scientists discover cures for the causes of death, undoing the damage freezing caused, and bringing them back to life.

About 2,000 people belong to the Cryonics Institute in Detroit — which charges $28,000 for its service; 173 members are frozen. When a member dies, the Cryonics Institute injects fluid into blood vessels, which freezes the body without damaging its cells by drawing water from the cells via dehydration. The Institute cools the body to minus 196 degrees Celsius, the temperature of liquid nitrogen. It holds members’ bodies in cylindrical tanks called cryostats. Family members visit the cold storage area, which they treat as a cemetery.

Dance with death

Author Hayley Campbell believes that death reveals “what is buried in the living.” She notes that experts advise that you can deepen your self-understanding by facing the reality of death before it shares your secrets. And that is Campbell’s driving motive. She doesn’t share the dead’s secrets; she shares the secret techniques of the living who tend to the dead. Neither Campbell nor her subjects seem especially fascinated by the macabre, and you needn’t be either to enjoy her straightforward reportage. Unsurprisingly, her subjects are happy to reveal the mechanics of their tasks, and none seem fixated upon death. Their professional remove from their vocations forms the consistent theme of this compelling, revealing dance with Death.