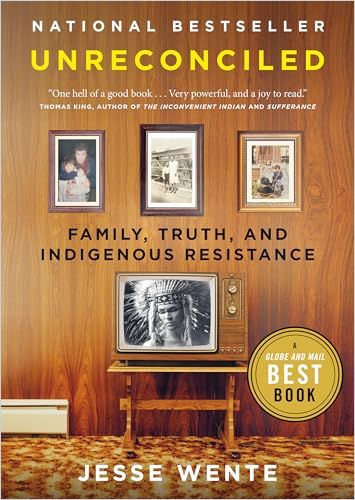

Anishinaabe tribe journalist Jesse Wente offers an insightful, sensitive journey through his developing understanding of his Indigenous identity.

An Indigenous Consciousness

Anishinaabe tribe journalist Jesse Wente, a former columnist for CBC Radio’s Metro Morning and the first Executive Director of the Indigenous Screen Office, details his upbringing and career in the majority white world and the destructive forces he regards as bent on eradicating Native Identity.

Toronto and Serpent River

When Wente was two years old, his family moved to a suburb of Toronto to live near his grandparents. His grandmother, Norma Meawasige, grew up on the Serpent River First Nations reserve near Elliot Lake, Ontario. Her parents’ main language was Ojibwe, and they lived a traditional life as Indigenous people.

The older generation of Wente’s family believed that assimilation, including English fluency, would offer their children more opportunities. They sent several of their children to Spanish Indian Residential Schools. The Natives who survived these schools endured severe psychological, sexual, and physical abuse. Wente’s grandmother emerged from the school traumatized, with no remaining desire to speak her native language. She moved to Toronto, married a white World War II veteran, and largely ceased to identify as Indigenous.

Separated from her family, her language, our stories, and our land, living with a white man, and spending her days waiting on colonial elites, my grandmother was in many ways a victory for residential schools. She was the exact type of Indian they hoped to produce.

Jesse Wente

Serpent River was a different universe from Toronto. Wildlife was abundant, and the Ojibwe carried guns in case they ran into something they could turn into dinner. Wente’s visits provided him with a sense of community and connection he lacked in Toronto.

Wente asserts that Canadian educational efforts fail to engage or respect First Nations, Metis, and Inuit values and culture. Residential schools were a government-sponsored, mass effort to eliminate Indigenous people, their languages, and their cultures. Government policies to erase Indigenous culture didn’t end until 1996 when Gordon’s Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan closed for good.

He reports that the educational achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people has worsened since 1996. Three significant reports – the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report; the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls; and the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples – suggest ways to reform Indigenous education, but the Canadian government has put few of these ideas into action.

Wente asserts compellingly that Indigenous communities must have sovereignty over their own educational systems. These communities need the resources to create and run schools and develop and implement Indigenous methods and curricula.

Where affluence and whiteness congregate, systems meant to support everyone suddenly do a better job of it.

Jesse Wente

Wente attended a blue-chip private boys’ school founded in 1913. After 75 years of excluding Indigenous students, the school proudly enrolled Wente as its first Native Canadian student. Wente decided he wanted to understand his own identity. He realized he couldn’t stop non-Indigenous people from viewing him as a caricature or stereotype. Wente understood that Non-Natives would always regard him only as Indigenous. He concluded that they ignored any qualities he possessed, especially when his actions violated widely held stereotypes of who Indigenous people should be.

When Wente was a student, Toronto police stopped him frequently. He realized this was happening because he was Indigenous. In Wente’s view, policing in Canada is rooted in racism and linked to the dehumanization of Indigenous people, denial of their rights, and systemic refusal to allow them self-determination.

A Token

Jesse Wente has loved movies ever since he was in high school. Working for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), he became North America’s first Indigenous film critic.

In another first, the prestigious Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) hired Wente as a film programmer. As the first Native Canadian to hold that role, Wente resolved to schedule Indigenous films and filmmakers. Wente worked with TIFF’s director on running its new home and building.

In time, Wente realized he was a token Indigenous staff member. Employing Indigenous people serves an institution’s public image, whether the institution is a university or an arts organization. Festival insiders ignored Wente when he pointed out that a film with major stars reinforced Indigenous stereotypes and further ignored him when lobbied to cancel its screening. He resigned. Wente eventually went on to use his expertise as the first Executive Director of the Indigenous Screen Office.

Indigenous Sovereignty

Cultural appropriation underscores the lack of authentic Indigenous voices in the public arena and promotes racism, inequality, and the dehumanization of Indigenous people.

Wente finds appropriation in institutions such as the Canadian Museum of History, the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Royal Ontario Museum. He explains appropriation as historically based and writes that Canada began with colonizing efforts that appropriated Indigenous lives, land, and culture, and then invented stories to justify its violence and greed.

Just stop. Stop taking our kids, stop robbing our communities, stop jailing us, stop dehumanizing us – just stop. It didn’t work.

Jesse Wente

“Reconciliation” between Canadians and Indigenous peoples has become a well-known political talking point. This attractive-sounding concept has allowed progressive governments to continue promoting familiar old agendas.

Wente regards the idea of reconciliation as implying that it started with a relationship that was once good, and then broke and was repaired, but Canada and the First Nations never had a good relationship.

Justified Outrage

Throughout his life, Wente experienced the destructive attitudes many Non-Natives hold toward Indigenous peoples. He concludes that attacks against them won’t stop unless these attitudes change. He regards the Canadian residential school system and the nation’s constant treaty violations as efforts to erase Indigenous identity and explains how their impacts persist. He also reports, on a more positive note, that today’s young Indigenous Canadians are learning their communities’ native languages, engaging with their culture, and embracing political action.

Wente is a superb writer, and though filled with outrage — and, at times, rage — he expresses his anger calmly and with clear articulation. By describing his life story in detail, Wente helps Non-Native readers understand the cultural schizophrenia of his upbringing and his difficult, circular journey to owning his identity in all its richness and complexity. Wente clarifies what it means to be an Indigenous Canadian living in an overwhelmingly white world. His work is instructive and powerful and told in a singular voice.