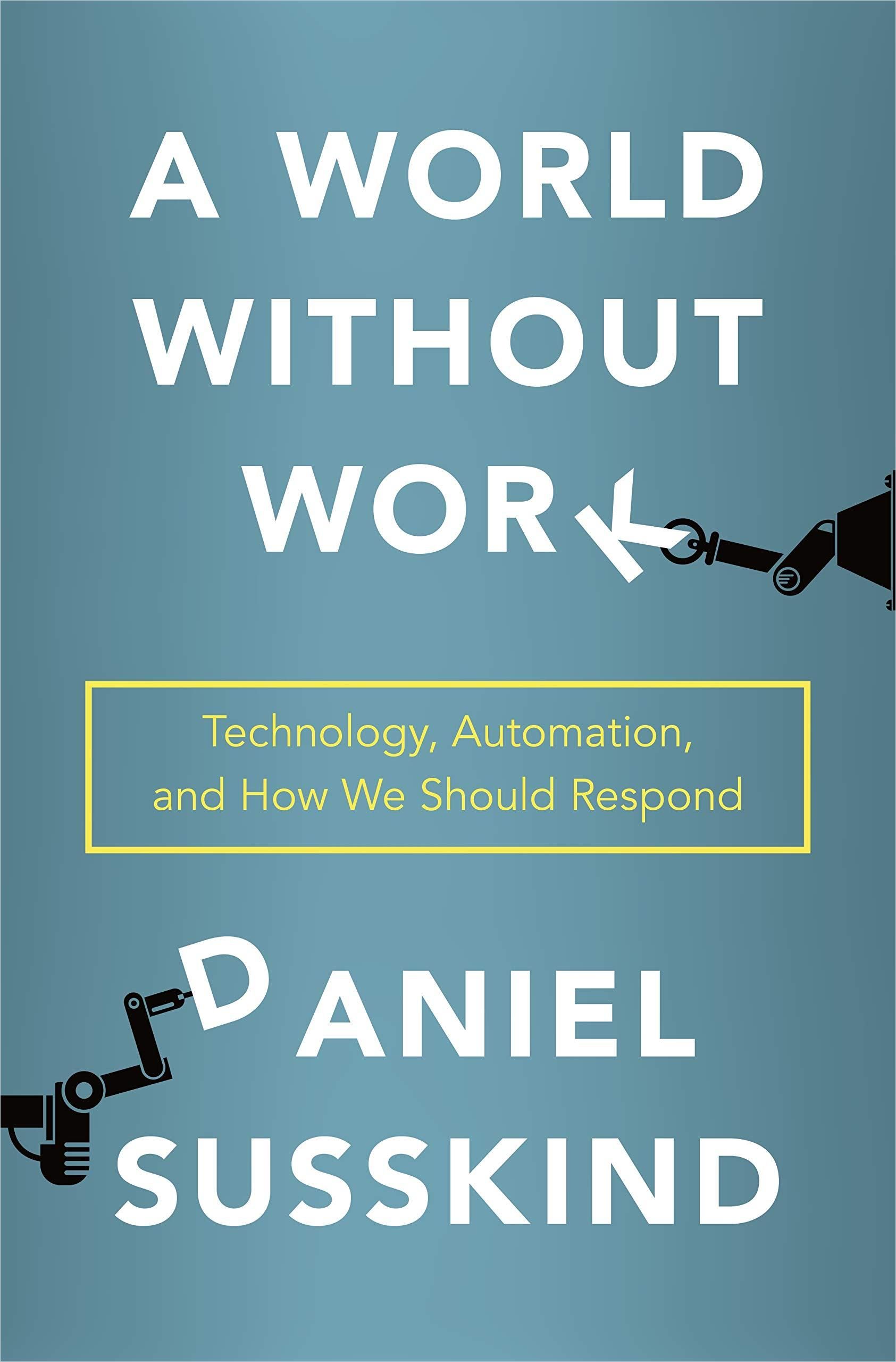

Recognizing that the Age of Labor is ending, Oxford economist Daniel Susskind argues for the Big State to help create a universal income to free people from work.

A Little Help from the Big State

In this New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice, Oxford economist Daniel Susskind argues that machines will create mass unemployment and that society should prepare for the Age of Labor to end. Comprehensive and elegantly readable, Susskind describes the threat AI poses to jobs and postulates an optimistic post-work world in which the state guarantees a safe livelihood. The Times said of Susskind’s work: “Should be required reading for any potential presidential candidate thinking about the economy of the future.”

Susskind has the credentials to wrestle credibly with these issues. A career development fellow in economics at Balliol College, Oxford University, he served as policy analyst and policy adviser for the British Prime Minister and Cabinet and was a Kennedy Scholar at Harvard University. He co-authored, with his father, Richard Susskind, The Future of the Professions. The Guardian called Susskind’s book, “An explainer rather than a polemic, written in the relentlessly reasonable tone that dominates popular economics: the voice of a clever, sensible man telling you what’s what.”

State Management

Susskind possesses the great gift of presenting complexity simply, a rare ability especially for an academic with a second career in policy. He sets his table by reminding you that automation has almost always created new jobs.

More and more working-age Americans…are abandoning the world of work altogether – and that should be a cause for alarm.

Daniel Susskind

But, Susskind laments, today millions of jobs may become obsolete faster than new jobs can replace them. His central thesis is that the Big State should help society create value in community-building, so everyone can enjoy the prosperity that machines will bring.

Considering AI

Susskind provides an overview that readers without a grounding in economics will find clear and informative. Machines, he states, removed craftsmanship and replaced it with repetitive tasks on assembly lines. Technological advances transformed society swiftly and comprehensively, but skilled and unskilled workers remained in high demand.

In a world with less work…we will need to revisit the fundamental ends once again. The problem is not simply how to live, but how to live well.

Daniel Susskind

Susskind notes that even the highest skilled jobs have routine elements. Routine tasks break down into discrete steps and prove easier to automate. He holds that jobs requiring creativity, judgment or interpersonal skills – mostly low-paid caregiving work – resist automation.

Outperforming Humans

Susskind points out something those not deeply familiar with AI may not realize: intelligent machines don’t have to possess human general intelligence (HGI). He urges you to abandon the idea that they must emulate human cognition in order to replace humans. Even without HGI, machines may appear that exercise judgment, empathy or creativity, and Susskind has little doubt that humans face obsolescence. The only exceptions, he says, will arise when equipment costs more than human labor. For example, car washes pay people to handwash cars for less than the cost of automatic washers.

For the moment, human beings may be the most capable machines in existence – but there are a great many other possible designs that machines could take.

Daniel Susskind

Machines will do many jobs better and faster, thus creating a world in which labor and the market no longer determine prosperity. Susskind asks the question that inspired and informs his inquiry: can the world distribute this prosperity more equitably?

Unequal Distribution

Technology exacerbates inequality as market mechanisms reward some people more than others. Capitalism only works, Susskind insists, if everyone has capital. He defines traditional capital as property, cash, investments, and anything traded on the open market. Human capital includes a person’s skills and experience. Wages reward these skills.

Prosperity has always been unevenly shared out in society, and human beings have always struggled to agree on what to do about that.

Daniel Susskind

But, the author warns convincingly, if technology outpaces people’s capacity to catch up, human capital may become valueless. Furthering this trend, technology drives globalization, which increases productivity while pushing wages down.

Not Production, Distribution

Susskind abhors the inequalities that now proliferate. He wants the Big State to increase taxes on those with reliable and valuable capital and distribute revenues to everyone. The Big State should tax big companies and a Universal Basic Income (UBI) would distribute that wealth. Susskind sees UBI as “one of those rare policy proposals that makes the political spectrum bend back on itself, with people on opposite ends meeting in violent agreement.”

The Big State, he posits, can create “citizens’ wealth funds” – publicly-held capital invested on behalf of citizens, pools from which they receive dividends. Susskind cites Norway as doing this with oil reserve wealth. He is adamant that this isn’t socialism. The state owns the capital, Susskind makes clear, but it doesn’t control its distribution. Combining income-sharing, capital-sharing and labor-supporting would, Susskind fervently believes, halt polarization and decline in Western societies.

Big Tech

Five of the ten most valuable companies in the world are tech companies. No one, Susskind fears, knows how to safeguard against their rampant growth. Building the massive digital infrastructure that dominates everyone’s lives costs a lot. Giant companies must create big network effects – drawing more people into the network exponentially increases its value. Big Tech firms therefore buy up smaller companies. This threatens to turn them into monopolies.

Susskind might surprise you when he suggests that monopolies might not be a bad thing. As an example, he details how Apple can afford to experiment, innovate and fail without going bankrupt. On the other hand, he forsees that by using algorithms, Big Tech could limit liberty, shape democracy and exercise judgment in social justice policy. Right now, he points out, no entity or authority exists over Big Tech.

Community-Building

There will be less work in the future, and what defines work may radically change. Leisure markets, says Susskind, designed to help shape people’s free time in imaginative ways, must replace labor market policies designed to make people useful in society.

In a world with less work, we will face a problem that has little to do with economics at all: how to find meaning in life when a major source of it disappears.

Daniel Susskind

A Conditional Basic Income (CBI), Susskind explains, would resemble a UBI with the added component of community service. This could be in cultural production, politics or caregiving.

Susskind proves an almost romantic optimist. He hopes people will find greater meaning and purpose when untethered from work’s obligations. His arguments are lucid and offered in finely-tuner prose. Tim Harford, author of The Undercover Economist, says, accurately, that, “Susskind… writes with such elegance that you don’t even notice how much you’re learning.”