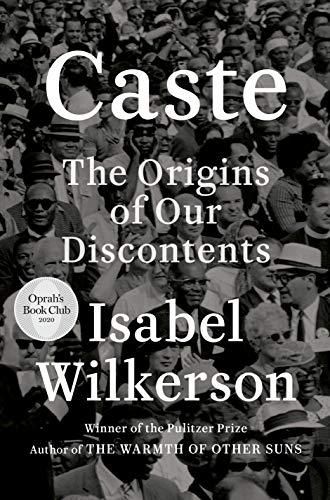

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson presents an indispensable overview of racism in the United States and its economic and social impacts.

A Classic of American History

Isabel Wilkerson, a New York Times reporter and winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award, teaches and lectures at major universities. Her masterwork on the racial underpinning of American society is deeply revelatory about the contemporary state of the nation and its return to vehemence about race.

Wilkerson describes a caste system profoundly embedded in American culture and society that evokes Germany’s darkest times. She regards this system as deliberately built on terror and lies spanning four centuries. Her unrelenting – and controversial – analysis harks to humankind’s capacity for evil, but offers hope that increasing numbers of white Americans will join in the demand for equality for all.

Time magazine named this the number one nonfiction book of 2020 and People, The Washington Post, The New York Times Book Review, O, The New York Public Library and Fortune also chose it among the best books of the year. Dwight Garner, writing in The New York Times, called it, “an instant American classic and almost certainly the keynote nonfiction book of the American century thus far.”

Superb ancillary readings of insightful non-fiction by Black Americans include Barack Obama’s memoir, A Promised Land, and Wilkerson’s Pulitzer Prize–winning The Warmth of Other Suns, a beautifully written saga of decades of Black migration out of the southern states.

The American Model

Wilkerson’s in-depth research reveals that in 1934, the Nazis recognized that America’s racial hierarchy, as enshrined in law, treated one group of people as subhuman, denied them opportunity and stripped them of legal protections and dignity.

America has an unseen skeleton, a caste system that is as central to its operation as are the studs and joists that we cannot see in the physical buildings we call home.Isabel Wilkerson

The author discloses that American laws and customs forced “the subordinate caste” into separate, inferior schools and housing, and sanctioned their beating, torture and murder by the dominant race. Shockingly, Wilkerson reports, the Nazis at first considered the US system too harsh. This is only one of numerous historical metaphors Wilkerson deploys with eloquence to demonstrate the degradations of racism. These examples seem particularly evocative for younger readers who may not have vested in this aspect of America.

Hierarchy

Wilkerson takes the reader through how America’s social hierarchy moves from white at the top down through yellow, brown, red and then Black people. This system endures, in part, she recounts, because middle-caste members can look down on others and feel that they’re not at the bottom. White, European settlers put forth the myth of Caucasian superiority to exploit and dominate the continent.

Systematic Racism

Wilkerson explains how systematic racism casts other people – especially Black Americans – as perpetually inferior. Slaveholders, she reminds readers, faced no condemnation for raping enslaved Black women and no Caucasian man or woman could form a legal romantic bond with a Black person – slave or free.

The author details how segregation laws treated Black people as a contaminating affront. Mass incarcerations, public assaults and unpunished murders of Black people reinforced inequality and the racist concept that some lives matter less than others. Only the Civil Rights Act of 1964, she stresses, guaranteed Blacks legal equality, and it still left a long road to travel.

White Americans

Wilkerson provides keen sociological insight into how white Americans consciously or subconsciously perpetuate racial divisions and the caste system.

By adulthood…most Americans have been exposed to a culture with enough negative messages about African-Americans that as much as 80% of white Americans hold unconscious bias against Black Americans.Isabel Wilkerson

Wilkerson breaks down how – no matter how destructive Donald Trump proved to be socially and economically – many white Americans prioritized maintaining the caste system. She allows her anger to surface when describing how after lower-income and marginalized white Americans voted for Trump, he gave tacit and direct encouragement to white supremacists.

Harm

Beyond rogue police officers killing Black men and women, Black Americans live, Wilkerson laments, on average, shorter lives and suffer higher rates of diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure than do Caucasians. She writes from experience of how Black Americans face small racist cuts daily that slowly kill the body and soul.

A caste system persists in part because we, each and every one of us, allow it to exist – in large and small ways, in our everyday actions, in how we elevate or demean, embrace or exclude, on the basis of the meaning of people’s physical traits.Isabel Wilkerson

Writing in her signature beautiful prose, the author presents a depressing, heartbreaking litany of the effects of the US economic and caste systems: White and Black Americans live in a country that can’t provide adequate health care and faces educational outcomes that fall far behind other wealthy nations. This is a country where more people suffer in prison than in any other nation, where babies and mothers die in childbirth, where older people die younger than in most other industrialized countries, and where a pandemic – one many nations managed better – proved crippling and tragic.

Unfairness

The author finds hope in that increasing numbers of Caucasian Americans now understand that caste structures harm everyone. She finds that they recognize that elevating subordinate castes to equality does not diminish the security or opportunities of the dominant caste.

Wilkerson shows admirable optimism in recognizing this new movement among the oppressive class. In the face of one enraging fact after another, the author demonstrates almost unbelievable restraint in not reverting to a rage-filled rant. Few authors on the other side of the political spectrum ever hold to the even tone Wilkerson maintains. Her rigorous scholarship allows her to present horror that, written more sensationally, might turn away readers away. While it will be controversial, this is already a classic in United States history and sociology, required reading for anyone seeking insight into American race relations and history.